Iceman (7 page)

Authors: Chuck Liddell

BEING MENTALLY TOUGH IS NOT A SOMETIMES THING

T

HE UNDERLYING THEORIES OF HAWAIIAN KEMPO

are the same as they've been since the Kempo form was first created by a Buddhist monk in AD 525. While visiting China to teach Buddhism to villagers, the monk saw them being robbed and beaten by bandits. He didn't believe in fighting, but he believed that not being prepared for a fight was a graver sin. For several days he fasted, until a vision of a new fighting style came to him. He taught the villagers how to defend themselves using an open hand and their feet, knees, and elbows. They would not always stop the marauders, but at least they could now defend themselves.

The tenets John preached were the same. If you couldn't pay for workouts, he didn't care. Most of the guys he trained weren't paying a cent. John was always saying, “I never let lack of money come between you and Kempo. All I ask is that you give Kempo and The Pit the respect and loyalty it gives you. Confidence, loyalty, and humility are what I expect from all Pit Monsters.”

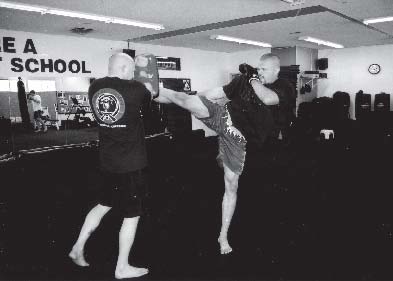

It wasn't easy to come by that confidence, but the humility was no problem. You couldn't just sign up for a trial membership to The Pit and decide if it was the right gym for you. You had to be invited by someone who was already training there. After my first few times, I would bring Eric. We were so close that he was once accused of being in a fight in collegeâwhile he was sitting at home watching TVâjust because I was there. He knew how much I wanted to be a kickboxer and made himself miserable trying to help me. He used to wince when we'd do drills that strengthened our shins. When we'd be driving over, his head would start hurting and I'd hear him whispering, “Please no sparring today, please no sparring today.” Eventually, though, he'd become a black belt. He was one of the few who survived the program.

There's no betterâor harderâplace to work out than The Pit.

Even with an invite from someone on the inside, there was no guarantee you'd become a lifetime member of The Pit. Every day you came to work out, you were going to be pushed to agony. Not just on the weights or the tires or the heavy bags, but in the ring. Sparring was a constant, and the sole purpose was for you to get beaten, until you decided you'd had enough or John decided you were ready. It may sound extreme. Hell, it

is

extreme. But John's purpose was clear: He wanted to separate those who were strong from those who were weak. And not just physically strong, but mentally strong.

Being mentally tough is not a sometimes thing. You don't turn it on and off. If you're not mentally tough in the gym while you are training, then when you're challenged in a fight, you will fold. It doesn't mean you have to be balls out every time you work out. But, when you are being pushed in training, you can't just fold a couple of times because you feel that you've done enough that day. Before you know it, when you get in a fight and are tired and beat-up and in a bad position, you will give up, too. That was the point of the beatings. If you were going to fight, you'd better be preparedâfor everything.

SIZE DOESN'T MATTER

F

ITTINGLY, THE HISTORY OF MIXED MARTIAL ARTS

and ultimate fighting began at the circus. Or, more accurately, in a booth next to the big tent that held the main events. It was in Brazil in the 1920s, and these fights were sideshows, no different from seeing the bearded lady or the man who swallowed knives. They held bouts the organizers called Vale Tudo, Portuguese for “everything allowed.” And it was. The more insane the matchup, the more popular the show. One Brazilian newspaper in the 1920s wrote about a large black man fighting a tiny Japanese man. The crowd expected the little guy to be pummeledâin fact, that's what they had paid to see. He was thrown to the ground by his opponent, an expert in the South American fighting style of capoeira, and was vulnerable. But as the looming giant readied to kick the man in the head, he was suddenly brought down. The Japanese man had used a deft jujitsu move to lock his opponent's leg before he could finish his kick, then rendered him unconscious with a few other deft maneuvers. After the short struggle, the fight ended with the Japanese man sitting on top of his felled opponent's chest.

This style of fighting was especially popular in Brazil, where Mitsuyo Maeda, a former Japanese boxing champ, had immigrated. When he arrived in Rio, Maeda found a benefactor in Gastão Gracie, a wealthy businessman. He took Maeda in, helped him get established, and became a leader in the movement to bring Japanese immigrants to Brazil. In exchange for his help, Maeda taught Gracie's sons the ancient art of jujitsu. Only he added a twist.

The Japanese jujitsu learned by Maeda when he was a boy in the late 1800s focused on using an opponent's force against him, which often led to throws and flips. But Maeda emphasized grappling and defending yourself from the ground. He taught submission holds, joint locks, and choke holds, making it a more violent, aggressive, and combative form of jujitsu than that taught in Japan. Three of the Gracie boysâCarlos, Carlson, and Hélioâtook to it instantly. It wasn't long before they opened their own academy, Gracie Jujitsu, and became known as the founders of Brazilian jujitsu.

The sport's popularity quickly spread across the country. Children practiced in the countryside, and the circus made it a regular part of its traveling road show. Everyone loved the choke holds, seeing men spasm as they became unconscious, and the joint locks that twisted elbows into gruesome angles. The Gracies were confident that their form of martial arts was superior to all others. They believed that when it was practiced properly and the right technique was used, size didn't matter. No matter how small they were and how big the opponent, they could not be beat. Shortly after perfecting their sport in the 1920s, Carlos inaugurated what became known as the Gracie Challenges. He challenged anyone throughout Brazil to battle him or his brothers in a fight to submission. The challenges became legendary within the country and lasted for decades. In 1952, Helio, then thirty-nine, participated in what is still the longest recorded fight in history, a three-hour-forty-minute loss to Brazilian judo expert Valdemar Santana.

Then in 1959, the original form of Vale Tudo fighting first appeared on Brazilian television, on a show called

Heróis do Ringue

(Ring of Heroes). Hosted by the Gracie boys, it featured no-holds-barred fights between competitors from all different disciplines. On the first show a Brazilian jujitsu expert named João Alberto Barreto battled a nationally known wrestler. Barreto quickly locked his opponent in an armbar, but the wrestler refused to tap out. Barreto slowly applied more pressure, expecting the match to end or the wrestler to give up, but he never did. Not until the arm snapped like a twig, leaving an exposed compound fracture for all of Brazil's television audience to see, was the fight stopped. The violence was so shockingâand the complaints flooded in so quicklyâthe show was immediately pulled off the air.

At the end of the decade, in 1969, Hélio's son Rorion left Brazil as a seventeen-year-old for a summer vacation in California. For three months he roamed around SoCal, sometimes working odd jobs, sometimes just spending the night on the streets. He loved it and had a vision of bringing his family's style of jujitsuâand its academiesâto the United States.

Nine years later, armed with a law degree and a lifetime of martial arts training, he moved to LA full-time. To make ends meet, Rorion cleaned houses, worked as an extra on such shows as

Hart to Hart

and

Fantasy Island

, and choreographed fight scenes for movies (such as that choke hold Mel Gibson uses on Gary Busey at the end of the first

Lethal Weapon

). He also set up a mat for training in his garage. The friends he made walking around Hollywood's lots as an extra became his students, spending afternoons, mornings, and evenings in his garage in Hermosa Beach, learning the arts of submission holds and choking people. Word about this Brazilian badass teaching jujitsu out of his garage began to spreadâone of those in-crowd secrets that so many Hollywood poseurs wanted in on. It helped that Rorion would challenge any dojo sensei to an anything-goes fight, right in front of the sensei's students, to prove how powerful Brazilian jujitsu could be. By the mid-1980s, classes became so large Rorion needed one of his younger brothers, seventeen-year-old Royce, to move from Brazil to help out. Hundreds of students were learning Gracie-style jujitsu, filling thirty-minute classes from seven in the morning until nine at night, seven days a week.

In 1989, Rorion opened the first Gracie Jujitsu Academyâfinally getting out of his garageâin Torrance, California. And within twenty years there would be Gracie academys in nearly every major town in the country. The Pentagon would hire Rorion's jujitsu experts as consultants to teach hand-to-hand combat. (Thanks to

Black Belt

magazine for letting me crib Rorion's history from one of its stories. As I said, I've been reading that magazine since I took my first karate class.)

Rorion produced Gracie jujitsu videos that developed a cult following among martial arts and combat sports fanatics. And to cement his rep and build his business, he brought the Gracie Challenges to the United States. Only now the winner didn't just get bragging rights that his form of combat was the best. Rorion also threw in $100,000 to whoever beat a Gracie jujitsu expert. He never had to pay up.

In 1991, Gracie met Art Davie, a Southern California ad exec, who was researching martial arts programs for a client. Davie eventually became a student and friend of Gracie's. He saw the popularity of the Gracie videos and often heard about Gracie's quest to constantly prove Brazilian jujitsu was the most dominant form of martial arts in the world. So in 1992 he proposed an idea to his teacher: an eight-man, single-elimination tournament in which any fighting style was allowed. They'd call it War of the Worlds. Gracie loved it, and he and Davie took it to John Milius, another student of Gracie's, who wrote

Apocalypse Now

and directed

Conan the Barbarian

. He loved it, too, and within a year they had sold the idea and had a show on pay-per-view.

Newly titled the Ultimate Fighting Championships, UFC 1 debuted on November 12, 1993, from McNichols Sports Arena in Denver. The show featured two kickboxers, a boxer, a karate expert, a shootfighter (the original term for mixed martial arts), a savate black belt (kickboxing with shoes), a sumo wrestler, and a smallâby comparisonâfrail-looking jujitsu expert named Royce Gracie. Among all his brothers and students, Rorion actually chose Royce for UFC 1 because he was the least physically threatening. He was the pawn to prove, if he won, that Gracie jujitsu was the most dominant martial art in the world.

The promoters knew how to create some drama. They billed the event as “no holds barred,” which was essentially true. They flew in João Alberto Barreto, the Brazilian jujitsu master whose breaking of an opponent's arm in a 1959 fight got the sport thrown off Brazilian television. They had a Hollywood designer design the Octagon. And they offered prize money of $50,000. The first UFC fight attracted nearly one hundred thousand pay-per-view buys.

It didn't take long for Royce to prove Rorion right. His first fight that night was against Art Jimmerson, the lone traditional boxer in the competition. Jimmerson was so mismatched, he used a boxing glove on one hand only, unsure of what exactly he was getting himself into. Royce needed just a few kicks to Jimmerson's lower body to take him down and mount him. Jimmerson didn't even wait for Royce to put him in a choke hold or any other submission move before he tapped out.

Royce needed even less time against Ken Shamrock in the semifinals of UFC 1. In this fight he proved how powerful the Gracie jujitsu style could be. Shamrock had an early advantage in the right, getting the dominant position. But with a few deft moves, Royce got the upper hand, literally. Fifty-seven seconds into the first round, he had Shamrock in a choke hold and forced him to tap out.

In the finals that night, Royce left no doubts that he was the world's ultimate fighter. He faced Gerard Gordeau, a boxer/kickboxer from Amsterdam. In his first match that night, Gordeau had hit his opponent, Teila Tuli, so hard that Tuli's teeth were knocked not just out of his mouth, but out of the ring, winding up beneath the announcer's table. The force was so strong it also broke Gordeau's hand, but it didn't matter. Gordeau won easily in the semifinals. But he was no match for Royce. Gordeau was at such a disadvantage at one point, the legend goes, he bit Royce on the left ear. Royce allegedly showed the bite mark to a camera crew covering the fight. One minute and forty-one seconds into the fight, Royce caught Gordeau in a rear-naked choke. He held on a little bit tighter and longer after Gordeau had submitted.

The win was no fluke. Five months later, at UFC 2, in a sixteen-man tournament with a $60,000 purse, Royce earned the title again, winning four fights in a row one night. In the last one he was punching his opponent so often and with such ease, the guy submitted just seventy-seven seconds into the fight. Royce bowed out of UFC 3 after an injury, but proved the power of Gracie jujitsu all over again in UFC 4. Fighting for $64,000, Royce made it to the finals of the tournament against Dan Severn, a 275-pound wrestler. Severn had been a four-time all-American at Arizona State and once held the U.S. record for most victories by pins.

That night he was clearly the stronger fighter. The match lasted a UFC title-fight record of 15:49, with Severn keeping Royce flat on the mat for most of it. But the ground moves the 180-pound Royce had been perfecting his entire lifeâthe types of moves his grandfather insisted could be used no matter how small he was or how big his opponentâwere eventually too much for Severn. From his back Royce maneuvered his legs so one of Severn's arms and his head were caught between Royce's thighs. It was a picture-perfect triangle choke. Slowly the blood flow to the hulking Severn's head was constricted, until he was forced to submit. For the third time in less than two years, Royce Gracie had won a UFC tournament. He had proven once and for all that his family's style of jujitsu was incomparable.