Iceman (22 page)

Authors: Chuck Liddell

PATIENCE DOES PAY OFF

B

Y BEATING TITO WHEN I DID, MY TIMING COULDN'T

have been better, both for me and the UFC. While Tito had been the first face of the rejuvenated sport, I was becoming the new face. It proved to me that patience does pay off. Meanwhile, mixed martial arts were only becoming more popular, more accepted, and more mainstream. My fight with Tito had been one of the biggest pay-per-view draws in the sport's history, making the UFC gobs of money and drawing in legions of new fans. And Dana had an idea that would help push it over the top.

He wanted to do a reality show. He'd put sixteen of the best unsigned mixed martial arts fighters in the country in one massive house in Vegas. There'd be eight middleweights (185 pounds) and eight light heavyweights (205 pounds), split into two teams with four fighters from each class on each team. The show winner in each weight class would get a contract to fight in the UFC. He wanted me and Randy Couture to be the team coaches. When the show was overâafter our two teams had spent weeks battling each otherâwe'd have our rematch. It was a brilliant schemeâwith only one major obstacle: Dana had no idea who would put it on the air.

HAVING A GOOD CHIN COMES NATURALLY

I

F DANA'S PLAN WORKED, THE SHOW WOULD BEGIN

airing for three months in January of 2005, with Randy and I having our rematch that April, at the end of the series. That meant I'd go a year without a fight. That wasn't going to happen. I'm not doing this to be a TV star, I'm a fighter.

A fight was set up for me for UFC 49 in August 2004 with a journeyman mixed martial artist named Vernon White. A small-time player in the game, he was always talking but not always backing it up. For years he'd been saying he deserved a fight with me, going so far as to claim that I was ducking him. Not likely. We had once tried to fight back when Dana was my manager, but the money wasn't good enough and Dana turned it down. Now, it was a good grudge match. Vernon had been around long enough that people knew who he was. He'd be a legitimate fight, a challenge, but not a huge risk.

Vernon began fighting in 1993, and by the time we finally hooked up he'd had nearly fifty MMA fights. While he couldn't talk a very good gameâor fight one, for that matterâhe was experienced. He knew how to cover up, how to take a punch, and how to get himself out of trouble. Plus, if you've had close to fifty mixed martial arts fights and haven't become anything more than a guy people fight to stay sharp, you're only in it because you like to get beat up or have nothing else to do. It's not because you think your next fight will be the one that puts you over the top.

By the sounds of the crowd during the introduction, it was clear that Vernon was a long way from winning any fans. When the cage announcer said his name, he was met with a few boos, but mostly indifference, which is actually worse than being hated. If you're going to do something as visceral and emotional as fighting, you at least want to get the crowd to pump you up. Whether they love you or hate you, it can motivate you. But for Vernon there was just disinterest. Joe Rogan said cageside, “I don't think I heard one clap for the guy.”

The reaction for me was a little different. As the crowd gave me a standing O, one of the announcers said, “Wanna be a crowd favorite? Knock out Tito Ortiz.”

We both came out aggressive. He threw a looping right that barely connected, then came back with a kick that missed. I connected with a good shot to his chin that dropped him, then we grappled for a few seconds. There was good action in the fight. He wasn't backing down, which I liked. But when I had him on the ground, he didn't give me many openings. He'd just cover, not fight. There were no vulnerable spots to hit. And I wasn't in the mood to just sit there. I hate to lose more than anything, but I don't just want to win because my opponent refuses to fight. From the ground I pushed up and gave him some room to stand. He looked confused, surprised that I was letting him get back on his feet. I actually had to motion to him to stand back up.

We went right back at each other. A big left from me, a low kick and big right that connected on the top of my head from him. I always love that look in an opponent's eyes when he knows he's hit me with a solid shot and then realizes that I'm not all that fazed. Having a good chin comes naturally. Nothing I know of can train you for that. That moment when an opponent is stunned that I wasn't rocked back is also crucial. It gives me an opening. Against Vernon, I threw a big right that knocked him down. I pounced and just pummeled him. I was throwing left after left against his head, with enough force that you could hear me grunting across the cage, even though the crowd was cheering. But none of the punches were doing any damage, which was frustrating. Vernon just spread his fingers against his head, and all I got was the back of his hand.

So I backed off again, he got up again, and I went at him again. This was becoming the rhythm of the fight. This time I got him with a looping right that nearly twisted his head right off his neck. Down he went. Again. And I let him back up, again, because I wanted to fight. I had spent a couple months training. I knew I might not get to fight again until Randy in April of 2005, which was eight months away. We danced around for a minute, then I just stood there, waiting for him to make a move. He went for a low leg kick, then took a wild swing that missed. So I knocked him down again. I was bored of just punching him while he wasn't even trying to move. He looked like a kid cowering in the corner, turning his head and begging the bully not to hit him. Finally, he got up again and this time showed some life. He tried a reverse kick and had me backing up a bit. I looked over to Hack and John Lewis in my corner, and they both gave me a look that said, “Knock him out already.” So I did. I caught him with a good right to his chin and he just dropped. He didn't make a move to cover himself up. The ref jumped in and called it with less than a minute left in the first round. It was a good punch. Good enough that it would become a staple on

UFC Unleashed

shows over the next several years.

YOU NEED TO BEAT SOMEONE OVER THE HEAD TO GET WHAT YOU WANT

I

T WAS A BRILLIANTLY CONCEIVED IDEA.

THE ULTIMATE

Fighter

pulled together all the elements that were making reality TV so popular. It had people desperate for a chance, from different backgrounds, forced to live together. It had a large cash prize at stake. It had competition. And the beauty was that none of it was contrived. Things were settled in the ring, not with votes and immunity and backstabbing. You don't like someone, get him in the ring and knock him the fuck out.

But nobody wanted it. Dana and the Fertittas pitched it to every network, and they all turned them down. This was a problem. Because, while the fights were drawing big pay-per-view buys and the sport was only getting more popular, it still wasn't a huge moneymaker. It lost close to $50 million the first three years Dana and the Fertittas owned the company. While it had made progressâfrom getting sanctioned by more than twenty states, to generating huge pay-per-view numbers, to getting on live-broadcast televisionâit needed one more hit to cross over. One that would show the broadest audience possible that this was not a sport of savages but of elite athletes who could punch, grapple, and force submission with skill. Looking back, it happened exactly as it should have. No one had ever accepted the UFC from the moment Dana and the Fertittas bought it. Every bit of success had come from Dana basically forcing people to appreciate the UFC by proving there was an audience. The suits who made the decisions wanted no part of the sport, until they saw the numbers. But even then, it was like cutting through layers and layers of bureaucracy. As the stakes got bigger, the skepticism grew, despite the proof Dana provided. Sometimes proof just isn't enough. You need to beat someone over the head to get what you want. This was just one more example, which is why Dana and the Fertittas decided to produce the shows themselves. They'd finance it, edit it, package it, then offer it up for free to whoever wanted it. It was a risk-free deal for some network that didn't know how lucky it was about to get.

Dana and the Fertittas spared nothing. They bought a huge house for the sixteen contestants to live in. In less than three months they converted an old warehouse into a UFC training center. It had mats, speed bags, an Octagon, dressing rooms, offices, and bigger-than-life-size posters of me, Randy Couture, and other high-profile UFC fighters for inspiration. Between crews, cars, props, production costs, food, and everything else, the show would cost $10 million to produce. There was no guarantee they'd make a penny back. It was just as likely they'd make the show and no one would ever see it as it was that a network would pick it up.

Still, when Dana described it to meâI'd coach one team and Randy Couture the otherâI wanted in, even though I hate reality shows. That people could see what we do, that a network was going to show fights for free on television, seemed to be exactly what the sport needed to break through. It was going to be important, and I didn't think I could miss out on it. My manager, who was one of Dana's close friends and had actually taken me on when Dana bought the UFC, strongly disagreed. The pay was crap, just $800 a week, and my manager wanted me to hold out for more. But I was also in the middle of negotiating a new deal, and my manager thought I should use this show as leverage. I wouldn't listen, this show was going to be too big, at least I thought. We became so contentious that he quit working for me when I decided to do the show. For a long time, he wouldn't talk to Dana either.

I moved out to Vegas in September, just after I had bought a new house. And I wasn't thrilled about taking off for two full months of being locked down in corporate housing. I was going to miss my kids, my house, my life in San Luis Obispo. I also finally understood why my friends who live in Vegas are always telling me living there sucks. Friends come to visit constantly, and for them, visiting Vegas is usually several days of strip clubs, bars, and not sleeping. But living there is different. I would tell my friends that I'd take them out, get them in where they wanted to go, but then they were on their own. I had to go home and get up in the morning.

Like everything else in the UFC, we were working without a script. Literally. The first day that we showed up at the training center to start shooting, we had no clue what we were going to do. Same was true for the next day and the next. We were still trying to figure out who these contestants were and whether they really were great fighters. Dana found one guy, Kenny Florian, after he lost an MMA fight in Revere, Massachusetts. This was reality in every sense of the word. Nothing about this show started off looking slick or packaged.

The rules for the guys in the house were pretty simple: You couldn't do anything. You want to create some tension in a house real fast? Put sixteen amped-up amateur fighters in there and tell them they can't watch TV, read books, listen to music, or go out. The only thing they can do is stare at each other, eat, and think about fighting. Otherwise, as Dana once told

Playboy

, “It's not good television. You don't want to tune in and see these idiots sitting around watching TV for eight hours or reading books. It's not easy. It starts to drive them crazy. Imagine me and you in a house together every day, training against each other and knowing that eventually we have to fight each other. These guys start to get on one another's nerves. They've got fifteen roommates, and the house is a mess because no one does the dishes. All these things build up.”

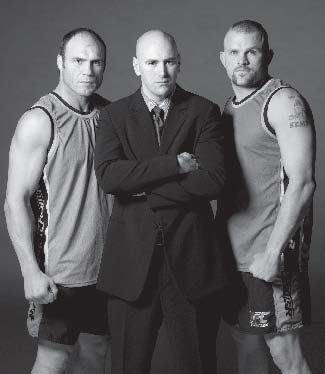

Me, Randy, and Dana from season one of The Ultimate Fighter. Team Liddell was strong, but we had some tension in the house. We're fighters, for God's sake.

It didn't take long either. On the first night in the houseâwhich was stocked with beer and liquorâseveral of the guys got drunk. One of them, Chris Leben, whose story line of instability dominated the first half of the season, actually pissed on another guy's bed while the guy was in the bathroom showering. Randy and I woke the guys at five the next morning; they had all slept around three hours, and some of them were still drunk, and we put them through a hellish workout. Guys were puking in buckets on the mat. They were hitting themselves in the side of their stomach to work out cramps rather than stop running. It was pure anguish, but also great television. These guys, like a lot of fighters, lived to the extreme. They pushed themselves to the brink when they were having a good time and past it when they were training. Eventually we had them working out more than four hours a day. In fact, that's all they were doing, which helped ratchet up the tension in the house.

Later in the show a light heavyweight named Stephen Bonnar, who was hysterically funny, got mad at a middleweight, Diego Sanchez, who was just plain weird, for cutting off asparagus tips and leaving the stalks behind. Diego's response: “I don't know what asparagus is.” (Before one fight Diego practiced yoga in a rainstorm because he thought he could harness the electricity from the clouds.) Another guy walked around in tight shorts that barely covered his ass and slathered himself in baby oil. These guys got bored, fast. So bored that Forrest Griffin had some of his roommates actually punching him in the faceâ¦for fun.

We had them doing some crazy stuff, too. Once they were broken down into two teamsâTeam Couture and Team Liddellâwe'd take them into the Mojave Desert for some challenges. The first pitted my light heavyweights versus Randy's. They had to carry us through an obstacle course while we were sitting in heavy recliners. They had to paddle a kayak across a dry lake bed, filling their boat with weights as they went along. They had to work as a team to carry a telephone pole from one spot to another, then saw it into four pieces, clamp the pieces back together, and carry it back. For those first few challenges, a person was eliminated from whichever team lost.

But, as I wrote, we were working without a script. And this was a show about fighting, not about stupid stunts in the middle of the fucking desert. We decided after one of the early challenges that each show should end with a fight between someone from the team that won the challenge and someone from the team that lost. Loser goes home. You'd think these guys would be dying to get into the cage and go at each other. But no one expected they'd actually be fighting until the finals of the show. The truth was, we didn't even know if they'd be fighting.

On the day the producers told the contestants they were going to step into the cage, Dana was in meetings with potential sponsors for the show. But Lorenzo Fertitta had stopped by to see what was going on. He listened as a producer explained there would be a fight after the next challenge. Before she could finish, the guys were asking how much they were going to get paid. She said, “You're not getting paid. You're fighting for a contract in the UFC. That's it.” That didn't sit well. I believe the response from one of the guys was “Screw that. We ain't fighting. We get paid to fight.” Here was the problem:

The Contender

, the show starring Sylvester Stallone and Sugar Ray Leonard, had just started airing on NBC right before we put everyone together. The season was three episodes old when our guys moved into the house in Vegas, and by then they knew that the boxers on

The Contender

were getting paid $25,000 per fight on the show. When they learned they'd be fighting for free on our show, well, they grumbled.

That made Lorenzo nervous. He called Dana and said, “What's going on down here?”

“What's going on where?” Dana answered.

“I'm on the set. And all these guys are saying they are not going to fight unless they get paid.”

“Dude, I am on my way down there. And I guarantee you they are fighting.”

All the guys had gone back home and were griping about fighting for free. Then, at 10:00

P.M.

, Dana called me, Randy, and the fighters back to the training center. Dana's a stocky guy with a shaved head who, even though he's not a fighter, would challenge any of these guys in a second. He's perfectly suited for his role as carnival barker of the UFC. That night, he gave a speech that is still written about in the dozens of UFC blogs. It's called the “Do You Want to Be a Bleeping Fighter?” speech. Here's how it goes:

“Gather around, guys, get close over here,” Dana said after walking into the gym. “I'm not happy right now. I haven't been happy all day. I have the feeling that some guys here don't want to fight. I don't know if that's true or not true or whatever, but I don't know what the bleep everyone thought they were coming here for. Does anybody here not want to fight? Did anybody come here thinking they were not going to fight? No? Speak up. Anyone who came here thinking they were not going to fight, let me hear it. Let me explain something to everybody. This is a very, and when I say

very

, I can't explain to you what a unique opportunity this is. You have nothing to bleeping worry about every day except coming and getting better at what supposedly you want to do for a living. Big deal, the guy sleeping next to you bleeping stinks or is drunk all night making noise and you can't sleep. You got bleeping roommates. We picked who we believe are the best guys in this country right now. We did. And you guys are it. Bleeping act like it, man. Do you want to be a fighter? That's the question. It's not about cutting weight. It's not about living in a bleeping house. It's about do you want to be a fighter. It's not all bleeping signing autographs and banging broads when you get out of here. It's no bleeping fun. It's not. It's a job, just like any other job. So the question is, not did you think you had to make weight. Did you think you had to do this. Do you want to be a bleeping fighter? That is my question. And only you know that. Anybody who says they don't, I don't bleeping want you here. I'll throw you the bleep out of this gym so bleeping fast your bleeping head will spin. It's up to you. I don't care. Cool? I love you all, that's why you're here. Have a good night, gentlemen.”

Then he walked out the door. The next day he promised that any fighter who knocked a guy out or forced him to submit would get a $5,000 prize. And the question of these guys getting paid for fighting wasn't an issue anymore.