Ice-Cream Headache (32 page)

Read Ice-Cream Headache Online

Authors: James Jones

He leaned his hand against the huge carved newel post. They would almost certainly be upstairs. One of the five bedrooms on the second floor still had an old bed in it intact with mattress. Emma knew where it was and that was where they would be. Excitement ran all through him. He had never been so hot. He started up the curving stairs and then stopped. He was so excited he was weak, and his knees were shaky. His breath was coming in short panting gasps, and wherever his breath flowed against the skin of his face it burned. He hesitated a moment and then sat down on the stairs and leaned back against the wall to catch his breath. Could sexual excitement, just plain sexual excitement, do all that to you? make you weak in the knees and out of breath? He guessed it could. He listened hard, and was sure he heard whispering and movement upstairs.

After a minute he got up again. He had to get up there, and right away; now. He had never been so excited and so hot in his life. This time he made four steps before he had to stop. Then he sat down again. His breath coming in short gasps, he rested his head back against the wall and stared at the huge wall painting two floors tall where it leaned above him at the bend of the stairs with its 18th century colonial figures in their knee britches and long dresses. He remembered how he had used to believe, even though you could feel with your hand the plaster of the wall under the painting, that the painting was a secret panel which opened onto a secret corridor and rooms in the middle of the house. It was when the cock-hatted, high-coiffured figures in the painting seemed to move, and then to actually change places in it, that he realized he wasn’t just only all excited and sexually hot, he was sick. Tom Dylan was sick.

He blinked, and the figures seemed to sort of move, reapportion themselves and go back to their original places. He felt woozy and half-drunk all over, and when he stuck out his lower lip and exhaled his hot breath up across the plain of his face, it actually seemed to sear his nostrils and lower lids. And when he shook his head the headache was still there, even stronger although the ice-cream which had caused it had long since been ingested. So was the stitch in his side still there, but now it was on both sides at once.

Somewhere, he did not know just where, the sexual heat and sexual excitement he had felt had ceased to be sexual excitement and become something else, a raging fever apparently. How could that have happened? It confused him. The two seemed to have fused in him, run together and into each other, so that he did not know when he was feeling sexual excitement or a fever, or both. He was as weak as a kitten. And the weakness wasn’t excitement weakness, it was sickness.

Oh, no!

he thought with a kind of silent inward wail of despair,

Oh, no!

There they were, up there, waiting for him. He was sure he had heard them. Two girls, ready to do anything he wanted. So near. He had waited for this a long time. He had waited for it all his life!

He struggled to his feet, took two more steps up the stairs and had to sit down quickly. How could this have happened to him? How could it have? Could it have been that cold wet night in the shivering Guard tent? But that had been eight days ago. Should he call to them? But what good would that do? Could they help him up the stairs? and place him on the bed between them? They wouldn’t. And by some adult instinct in his boy’s psyche he knew that if the opportunity was lost now, it would never come again. Girls were notoriously fickle about their sex. The chance was here and it had to be seized now. And yet he couldn’t.

God. Was it going to go on like this forever? Runner-up in the boxing tournament? Second choice for the scholarship? Always a bridesmaid and never a bride? Was it some kind of punishment? Sitting on the stairs, he shook his drooping head, and noted that his ice-cream headache had gotten even worse.

Besides, he was scared now. He wanted to be home. He was really sick. Slowly he stood up, and looked up at the fortress heights of that second floor which he had not been able to scale. Then he looked down the length of the staircase, and began to beat his retreat back from the high point of his advance. He had made it up ten steps. The staircase, and the bannister which he clutched, as if they were made of flexible materials seemed to sway back and forth weirdly with each step down.

He made it to the basement window and out and around to his bike. Maybe it was a punishment, a bad punishment. Maybe he was going to die, as a punishment. Pictures of his grandfather in his youth rose up around him, those old tintypes, with the hard eyes, and the mustache which hid the mouth so you could not see if it was gentle or stern. But you knew it was stern. Because in the movie his grandfather striding down Main Street on Saturday night in his Western hat had begun to pistolwhip over the head a roustabout who, bleeding, turned out to be Tom’s father while Tom, a very little boy, hid behind the bank building beside the filling station and watched. All he wanted now was to be home, as fast as possible. Home with his mother. Yeah, a lot of help she would be. A lot of help. The white cardboard placard said in bold black letters below the stern eyes, Wyatt Earp mustache and long black hair, EDWARD DYLAN FOR SHERIFF. Across the top in smaller letters was printed TRUST YOUR LAW. The right eye and eyebrow turned slowly into one of the women’s crotches from one of his pornographic pictures. Slowly it winked at him. The woman’s face smiled at him from above it. Then it began to revolve. Then the left eye and eyebrow turned into another one from another picture. The widow’s peak at the hairline became a third, the mustache over the mouth a fourth. Then the entire picture became covered with them, revolving, revolving.

The bicycle seemed to be driving itself. Breasts, crotches, delicious shaved armpits, delicious unshaved armpits, sixguns, mustaches, Western hats all revolved around each other now, turning, merging, separating, disappearing, reappearing, glaring and then dimming as great lights flashed. Tom shut his eyes, but the pictures did not go away anyway. His grandfather’s placard had faded away somewhere. Then it came back, zooming to hugeness with a screaming noise. Punishment! Punishment! Tom kept his eyes closed. The bike pedals felt light as feathers. Then he heard Doctor Sachs’s voice say somewhere, “I think it’s passed.” He opened his eyes and saw Doctor Sachs’s haggard face staring down at him in the bed. It appeared to be his mother’s and father’s bed, in their bedroom. His mother, haggardfaced also, was standing down at the foot of it, looking at him too. He could see them, but he could not understand them.

“You’ve had several pretty bad days there, boy,” Doc Sachs said with a tired smile. “A lot of people don’t get over double lumbar pneumonia.”

Tom did not understand him. He could only breathe in the very top part of his chest without it hurting him. But he felt he had to try to explain it to them anyway. “It’s not that,” he said clearly. He knew what he was saying, but his mouth did not feel as though it was working right. “Nothing’s that bad. Nothing is ever that bad. There’s nothing in the world that’s ever that bad. And they should never have let him do it to them. Guilty like that.”

“What’s he talking about?” he heard his mother say.

“Don’t know. Mumbling something about guilt,” Doc Sachs said. “He’s still pretty delirious, with the fever.”

Tom looked at his mother. She was so awful. The poor thing. She had cared, he guessed, from her face. Suddenly the woven wicker floorlamp with its faded pink shade appeared in front of and over her but he could still see her through it like the two images in a double-exposed photographic negative. “And I’ll fix it for you,” he babbled. “I promise I will.” He made a claw of his fingers and clawed the air with them, as if combing something. “I’ll buy you a new one. A whole brand-new one if you want it. When I make the money.”

“What’s he talking about now?” Doc Sachs asked.

“I don’t know,” his mother said.

Tom found he didn’t know himself. “A new one,” he insisted. If only she would understand. Or anybody. Guilt? Guilt?

“He’ll be all right now,” Doc Sachs said, and sighed, getting up. “He’s a tough kid. All the Dylans are tough. He’s probably got a helluva headache, right now. That fever and all.”

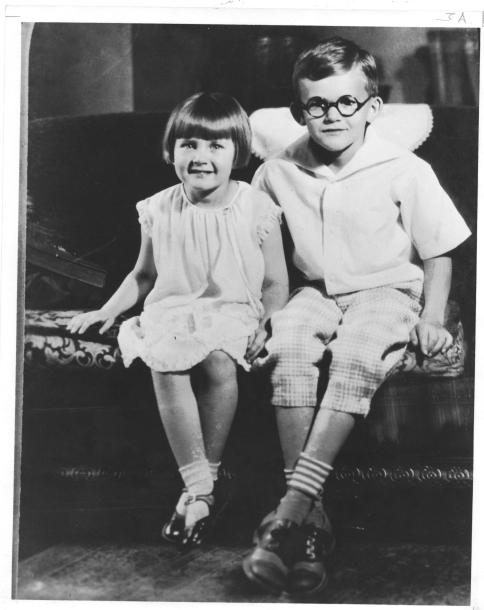

James Jones (1921—1977) was one of the preeminent American writers of the twentieth century. With a series of three novels written in the decades following World War II, he established himself as one of the foremost chroniclers of the modern soldier’s life.

Born in Illinois, Jones came of age during the Depression in a family that experienced poverty suddenly and brutally. He learned to box in high school, competing as a welterweight in several Golden Gloves tournaments. After graduation he had planned to go to college, but a lack of funds led him to enlist in the army instead.

Before war began he served in Hawaii, where he found himself in regular conflict with superior officers who rewarded Jones’s natural combativeness with latrine duty and time in the guardhouse. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, which Jones witnessed, he was sent to Guadalcanal, site of some of the deadliest jungle fighting of the Pacific Theater. He distinguished himself in battle, at one point killing an enemy soldier barehanded, and was awarded a bronze star for his bravery. He was shipped home in 1943 because of torn ligaments in his ankle, an old injury that was made much worse in the war. After a period of convalescence in Memphis, Jones requested a limited duty assignment and a short leave. When these were denied, he went AWOL.

His stretch away from the army was brief but crucial, as it was then that he met Lowney Handy, the novelist who would later become Jones’s mentor. Jones spent a few months getting to know Lowney and her husband, Harry, then returned to the army, spending a year as a “buck-ass private” (a term which Jones coined) before winning promotion to sergeant. In the summer of 1944, showing signs of severe post-traumatic stress—then called “combat fatigue—he was honorably discharged.

He enrolled at New York University and, inspired by Lowney Handy, began work on his first novel,

To the End of the

War (originally titled

They Shall Inherit the Laughter

). Drawing on his own past, Jones wove a story of soldiers just returned from war, presenting a vision of soldiering that was neither romantic nor heroic. He submitted the 788-page manuscript to Charles Scribner’s Sons, where it was read by Maxwell Perkins, the legendary editor of Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Thomas Wolfe. Perkins rejected it, but saw promise in the weighty work, and encouraged Jones to write a new novel.

Jones began writing

From Here to Eternity,

a story of the war’s beginning. After six years of work, Jones showed it to Perkins, who was fully impressed and acquired the novel. After Perkins’s death, the succeeding editor cut large pieces from the manuscript, including scenes with homosexuality, politics, and graphic language that would have been flagged by the censor of that era, and published the novel in 1951. The story of a soldier at Pearl Harbor who becomes an outcast for refusing to box for the company team, it is an unflinching look at the United States pre-WWII peacetime army, a last refuge for the destitute, the homeless, and the desperate. The book was instrumental in changing unjust army practices, which created a public outcry when it was published. It sold 90,000 copies in its first month of publication and captured the National Book Award, beating out

The Catcher in the Rye

. In 1953 the film version, starring Burt Lancaster and Montgomery Clift, won eight Academy Awards, including Best Picture, and made Jones internationally famous.

He returned to Illinois to help the Handys establish a writers’ colony. While living there he wrote his second novel,

Some Came Running,

which he finished in 1957. An experimental retelling of his Midwestern childhood, it stretched to nearly 1,000 pages and drew little acclaim.

In 1958, newly married to Gloria Mosolino, Jones moved to Paris, where he lived for most of the rest of his life, spending time with his old friend Norman Mailer and contributing regularly to the

Paris Review

. There he wrote

The Thin Red Line

(1962), his second World War II epic, which follows a company of green recruits as they join the fighting in Guadalcanal; and

The Merry Month of May

(1970), an account of the 1968 Paris student riots.

The Thin Red Line

would be brought to the screen by director Terrence Malick in 1998.

Jones and his wife returned to the United States in the mid 1970s, settling in Sagaponack, New York. There Jones began

Whistle

, the final volume in his World War II trilogy, which was left unfinished at the time of his death. However, he had left extensive notes for novelist and longtime editor of

Harper’s Magazine

Willie Morris, who completed the last three chapters after Jones’s death in 1977. The book was published in 1978.

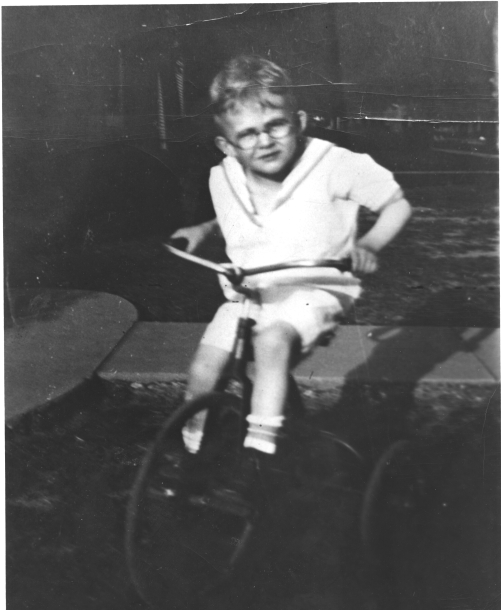

A young Jones, riding his bike in 1925.