I Won't Let You Go (12 page)

Read I Won't Let You Go Online

Authors: Rabindranath Tagore Ketaki Kushari Dyson

Tagore’s need for a feminine touch in his daily life as well as his deeper artistic need to be inspired by a woman remained with him, to be filled, from time to time, more or less, by various women of the family and later by other attractive women who clustered round him, drawn by his personality and fame. From an early period, from before Mrinalini’s death, his niece Indira Devi, the daughter of Satyendranath and Jnanadanandini, was very close to him. Just a couple of months older than Mrinalini, Indira was the recipient of some of Tagore’s most brilliant letters (

Chhinnapatrabali

, 1960). After the death of his daughter Bela, Tagore found comfort in the company of the young Ranu Adhikari, later the noted arts patron of Calcutta, Lady Ranu Mookerjee. She inspired the character of Nandini in the play

Raktakarabi

(1926) and was the recipient of the letters of

Bhanusimher Patrabali

(1930).

Tagore outside the villa Miralrío, San Isidro, Argentina, 1924.

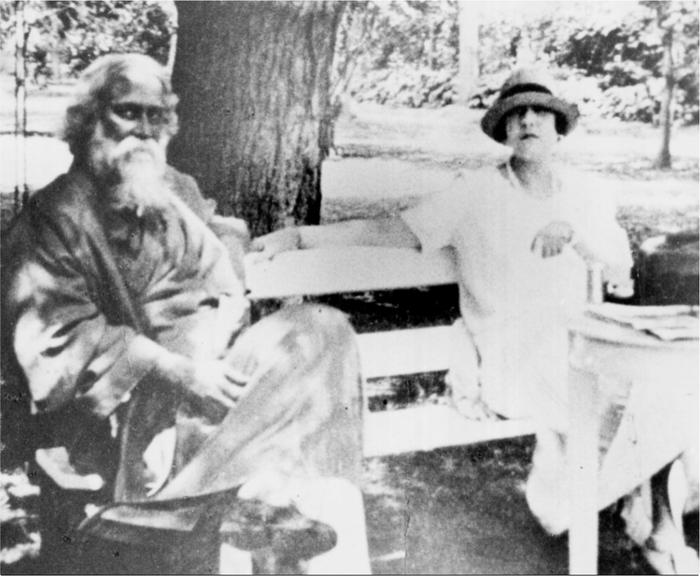

Tagore with Victoria Ocampo in Argentina, 1924.

In 1924 in Argentina Tagore met Victoria Ocampo (1890-1979), a young Argentine woman who was an ardent admirer of his works, and who later became a distinguished woman of letters and the founder and director of

Sur

, which has been called the most important literary magazine to emerge from Latin America in the present century, and of the publishing house of the same name. For two months Tagore and his honorary secretary and travelling companion Leonard Elmhirst were her personal guests. Tagore was stirred by this encounter, and a triangular friendship sprang up between himself, Victoria, and Leonard Elmhirst. Victoria was the dedicatee of

Purabi

(1925) and continued to be a distant Muse for Tagore in the last years of his life, playing a role also in his

development

as a visual artist. Tagore cherished hopes that she might visit him at Santiniketan, but although they met once more, in France in 1930, when she managed to organise his first art exhibition, she never made it to India. References in Tagore’s later poetry to the pain of separation and the enigmatic image of a woman who had failed him in some way may be linked to this experience.

22

In 1926, disappointed in his hopes of meeting Victoria in Europe, Tagore took consolation in the company of the attractive Nirmalkumari (Rani) Mahalanobis. Mrs Mahalanobis and her

husband

were Tagore’s travelling companions for the major part of his European travels in 1926, and she was the recipient of the letters of

Pathe o Pather Prante

(1938). Tagore also received substantial companionship from Rathindranath’s wife Pratima Devi, who was encouraged to develop her artistic talents and was a very supportive daughter-in-law to him in his later years. And there were other women from whom he received emotional support in his long life as a widower, as well as other bereavements of those close to him, besides the ones I have enumerated.

After a life of incessant creative activity, Tagore died, at the age of eighty years and three months, on 7 August 1941, in the family house in Calcutta where he had been born. The quality and quantity of his achievements seem all the more astonishing when placed against the amount of grief he had to cope with in his personal life. Much of his poetry is necessarily about love and suffering, about how one copes with loss, and can be called

passional

in the radical sense. Yet he is at the same time one of the most affirmative and celebrative poets of all times. I hope readers of this volume will see for themselves that he was neither ‘a hoaxer of good faith’ nor ‘a Swedish invention’, but a genuine poet who still speaks to us.

1

. Ghulam Murshid,

Reluctant Debutante: Response of Bengali Women to Modernization,

1849-1905

(Sahitya Samsad, Rajshahi University, 2nd

impression

, 1983), pp. 49-50.

2

. Krishna Kripalani,

Rabindranath Tagore:

A Biography

(Visvabharati, Calcutta, 2nd edition, 1980), p. 16.

3

. Kripalani, pp. 14-15.

4

. Kripalani, p. 89.

5

. Vera Brittain, ‘Tagore’s Relations with England’,

A Centenary Volume, Rabindranath Tagore,

1861-1961

(Sahitya Akademi, New Delhi, 1961), p. 118.

6

. Kripalani, p. 235.

7

. Tagore’s influence on Jiménez is discussed in Sisirkumar Das &

Shyama-prasad

Gangopadhyay,

Sasvata Mauchak: Rabindranath o Spain

(Papyrus, Calcutta, 1987).

8

. For more information, see my book

In Your Blossoming Flower-Garden: Rabindranath Tagore and Victoria Ocampo

(Sahitya Akademi, New Delhi, 1988), pp. 65-66 and 347; further references are provided in the notes. Borges’

comment

can be found in Jean de Milleret,

Entretiens avec Jorge Luis Borges

(Editions Pierre Belfond, Paris, 1967), p. 240. Victoria Ocampo showed how absurd the comment was in her article ‘Fe de erratas (

Entrevistas

Borges-Milleret

)’,

Testimonios

, vol. 9 (Sur, Buenos Aires, 1975), pp. 240-47.

9

. See my book

A Various Universe: The Journals and Memoirs of British Men and Women in the Indian Subcontinent,

1765-1856

(Oxford University Press, New Delhi, 1978), pp. 19-26, where further references can be found.

10

. Quoted in Michael Edwardes,

British India,

1772-1947

(Sidgwick & Jackson, London, 1967), pp. 122-27.

11

. Prabhatkumar Mukhopadhyay (editor),

Gitabitan:

Kalanukramik Suchi

(vol. 1, Santiniketan, 1969; vol. 2, Tagore Research Institute, Calcutta, 1978).

12

. Henry Yule & A.C. Burnell,

Hobson-Jobson: A Glossary of Colloquial Anglo-Indian Words and Phrases, and of Kindred Terms, Etymological, Historical, Geographical and Discursive,

first published in 1886; new edition, edited by William Crooke, 1903 (Routledge & Kegan Paul, London, 1969).

13

. W.W. Hunter,

A Statistical Account of Bengal

(London, 1877), quoted in Ghulam Murshid,

Rabindravisve Purbabanga Purbabange Rabindracharcha

(Bangla Academy, Dhaka, 1981), p. 45.

14

. Kim Taplin,

Tongues in Trees: Studies in Literature and Ecology

(Green Books, Bideford, Devon, 1989), p. 20.

15

. The idea is developed in several of David Bohm’s books, including

Wholeness and the Implicate Order,

first published in 1980, known to me in a paperback edition (Ark Paperbacks, Routledge, London, 1988).

16

. Prasantakumar Pal,

Rabijibani

, vol. 2 (Bhurjapatra, Calcutta, 1984), pp. 41-43, or vol. 2, 2nd edition, Ananda, Calcutta, 1990, pp. 11-14, 29-32.

17

. Pal, op. cit., vol. 2, 1st edition, pp. 268-72, or 2nd edition, pp. 204-07.

18

. Ketaki Kushari Dyson,

Rabindranath o Victoria Ocampor Sandhane

(Navana, Calcutta, 1985), pp. 318-36.

19

. Rabindranath Tagore’s letter to his son Rathindranath, 19 Baishakh 1317,

Chithipatra

, vol. 2 (Visvabharati, 1942), pp. 9-10.

20

. Rathindranath Tagore,

On the Edges of Time,

2nd edition (

Visvabharati

, Calcutta, 1981), p. 21.

21

. Rathindranath Tagore,

Pitrismriti

(Jijnasa, Calcutta, 2nd edition, 1387), p. 81.

22

. For further details, see my study

In Your Blossoming Flower-Garden.

[1991]

From a luminous shore into an ocean of darkness

leaped a star

like a madwoman.

They stared at her, the innumerable stars,

astonished

that the speck of light, their erstwhile neighbour, could

vanish in an instant.

She’s gone

to the bottom of that ocean

where lie the corpses of

hundreds of dead stars,

whom anguish of mind has driven to suicide

and the eternal extinction of light.

O why? What was the matter with her?

Not once did anyone ask

why she abandoned her life!

But I know what she would have said in reply

had anyone posed the question.

I know what burned her

as long as she was alive.

It was the torment of laughter,

nothing else!

A burning lump of coal, to hide its dark heart,

maintains a continuous laughter.

The more it laughs, the more it burns.

So, even so did laughter’s

fierce fire

burn, burn her without end.

That’s why today she’s run off in sheer despair

from a brilliant solitude full of stars

to the starless solitude of darkness.

Why, stars, why do you

mock her and laugh like that?

You’ve not been harmed.

You shine as you did before.

She’d never meant

(she wasn’t that arrogant)

to darken you by quenching herself.

Drowned! A star has drowned

in the ocean of darkness –

in the deep midnight

in the abysmal sky.

Heart, my heart, do you wish

to sleep beside that dead star

in that ocean of darkness

in this deep midnight

in that abysmal sky?

[Calcutta, 1880?]

Come, sorrow, come,

I’ve spread a seat for you.

Pull, rip out each blood-vessel from my heart,

place your thirsty lips on each split vein

and suck from my bloodstream drop by drop.

With a mother’s affection I shall nurture you.

My heart’s treasure, come you to my heart.

Within my heart’s nest cosily you may sleep.

Ah, how heavy you are!

A few of my veins may burst,

but what do I care?

With a mother’s affection I shall carry you

even on my feeble breast.

Sitting alone at home,

in a continuous drone

I shall sing lullabies in your ears,

until your weary eyes

are lulled to sleep.

My breath, drawn from my innermost recesses,

will fan your tired forehead;

you’ll sleep in peace.

Come, sorrow, come.

My heart’s full of such longing!

Press your hands on your mouth,

fall tumbling on my heart’s ground.

Like an orphaned child cry loudly within me once

till it echoes in all my heart.

In my heart of hearts there’s a musical instrument

that’s broken.

Pick it up with your hands,

play it with all your strength,

like a madman strum it twang twang.

Instrument and strings –

if they break, let them.

Never mind, pick it up,

play it with all your strength,

like a madman strum it twang twang.

Bruised by sharp sounds,

all the echoes, troubled,

will cry out in chorus

in pain.

Come, sorrow, please come.

Oh, how lonely this heart is!

Just do this, nothing else:

come close, lift my heart’s face,

set your eyes on it

and gaze.

This homeless heart

wants a companion –

that’s all.

You, sorrow, come, keep it company.

You may not wish to speak;

just sit without words

day and night by my heart’s side.

When you want to play,

you can play with it,

for my heart does need a playmate.

Come, sorrow, treasure of my heart.

Right here I’ve spread your seat.

Whatever little blood

is left in my heart of hearts,

all of that you may drain if you wish.

[Calcutta, autumn 1880 (Kartik 1287)?]