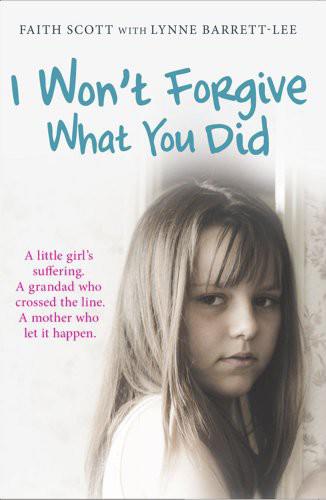

I Won't Forgive What You Did

Read I Won't Forgive What You Did Online

Authors: Faith Scott

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Child Abuse, #Personal Memoir, #Nonfiction

I W

ON’T

F

ORGIVE

W

HAT

Y

OU

D

ID

First published in Great Britain by Pocket Books, 2010

An imprint of Simon & Schuster

A CBS Company

Copyright © 2010 Faith Scott with Lynne Barrett-Lee

This book is copyright under the Berne convention.

No reproduction without permission.

All rights reserved.

The right of Faith Scott and Lynne Barrett-Lee to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

Simon & Schuster UK Ltd

1st Floor

222 Gray’s Inn Road

London WC1X 8HB

Simon & Schuster Australia

Sydney

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available

from the British Library.

ISBN: 978-1-84983-156-7

eBook ISBN: 978-1-84983-157-4

PTypeset by Hewer Text UK Ltd, Edinburgh

Printed and Bound in Great Britain by

CPI Cox & Wyman, Reading RG1 8EX

ART

O

NE

C

HAPTER 1

Though he was only in his sixties in 1963, when I was eight, Grandpops always seemed old to me. He had a bald head with just a little white hair remaining, which ran in a semicircle round the back of his head. He still had enormous black eyebrows, however, which sat above round tortoiseshell glasses.

He was short, and he always dressed the same – waistcoat, white open-necked shirt, no tie, battered black boots and baggy trousers. He also had a peaked cap that he wore everywhere. Even indoors it rarely came off. For some reason Grandpops always wore a suit jacket, often with another jacket over it. The pockets were filled with all manner of things: screws, pens, washers, filthy hankies, betting slips and, most importantly to me, sweets.

His hands seemed large, but then, when I was little, most men’s did, probably because when they touched me that was what I noticed. Pops’ were dark brown and dirty, just like his teeth, which were rotting and broken, with several missing. He had horrid breath, and fingernails that were broken and snagged. He always smelled of alcohol when he came to our house, because he’d spend several hours in the pub before he visited, intermittently leaving to visit the betting shop, to gamble on the horses. It was from here that he used to either stagger down the hill or catch the bus to our house, invariably laden with flowers and vegetables from his garden, which he’d bring for my mother. Sometimes, he was so drunk that he fell over on the pavement and at least once had to go to hospital for stitches to his head. Despite his appearance and manner my mother was very close to him. My father, conversely, seemed to hate him.

Pops always visited on Saturday; had done for as long as I could remember. We’d sometimes have to get the bus to see him in the week, too, more often than not at his house. Pops’ house was just the same as Pops – filthy and full of junk, it smelled of wine and dirt, and inside the walls were covered in black mould. The huge table in the kitchen was always covered in dirty, half-drunk tumblers of wine, similarly half-consumed bottles, gone-off food – usually cheese, bread and fried eggs – and, on the Rayburn, there was often a saucepan of some unpleasant-smelling stew. There were various buckets, in which all kinds of things fermented: dandelion, rhubarb, parsnip, carrot, and every type of hedgerow fruit that could be used to make alcohol.

He had been a sniper in the war and was a good shot, and would stand by the door to his kitchen shooting blackbirds with his rifle. I couldn’t bear seeing the poor blackbirds fall from the sky, fence or tree. He also had a menacing-looking handgun, which he kept under his pillow, and I always used to think that, if I upset him, one day he would use it on me. Ironically, he always used to try to stoke my fear, but in an entirely different direction. Keep away, he used to tell me, from ‘bastard Ken’, who lived next door. ‘He can’t be trusted around little girls.’ He’d often shoo me indoors, and lock us both in for good measure, which scared me almost as much. Even if we just went down the garden, he’d lock the door, because he said Ken was a thief and would go into his house and steal his things. Pops also told me Ken would go into his garden, when Pops was out, and dig up his vegetables and flowers to give to women he fancied, pretending he’d grown them himself. And according to Pops, sometimes he put poison in Pops’ garden, which was why his crop was poor at times. It was confusing listening to what Pops believed about Ken, and scary. Nowhere and no one felt safe.

I watched his arrival now, from behind the kitchen door, the place I habitually stationed myself on Saturdays, when he came to visit. My mother being her father’s daughter in most ways, meant our house, only the second I had lived in, was every bit as filthy as his. It was bigger than our first home, quite large in comparison; if it hadn’t been quite so full of rubbish – it had a sitting room, dining room and kitchen, all connected – I could have run around it in a circle. As it was, the dining-room doors always remained closed because it wasn’t a room we could use. There wasn’t any space left in it, because it was full of clothes and newspapers and crockery.

Back then, I didn’t know why Pops frightened me so much, only that I felt the familiar anxiety well up as he tried to coax me from where I was standing. One Saturday, I remember, he was in the kitchen talking to my mother, who was making him his usual cup of tea. In his hand were the sweets, several packets, which he would have bought on the way. Sometimes it would be Fruit Pastilles, or maybe Love Hearts, and at Easter, an Easter egg, made from cheap, odd-tasting chocolate. But Fruit Gums were the ones I loved best, because I could hold them tightly in my hand to warm them up a little, which made them tastier and easier to chew. I could see one of the packets today was Fruit Gums.

‘Come and get them, then,’ he said. Pops never used my name. ‘Come on. I’m not going to hurt you.’ As was always the case, I felt crushed by indecision, unable to make up my mind. I couldn’t work out what was the matter with me. Why did I hesitate? Why did I feel so much fear? I was only being offered sweeties, for goodness’ sake. ‘I’m not going to hurt you.’ He said this a lot. But I needed to work out from the tone of his voice whether, this time, he actually meant it; whether he

would

‘get me’, because if he did – and he mostly did – I felt panicked and trapped because I couldn’t get away and, much as I was desperate to shout ‘Help! Stop tickling me!’ no sound would come out of my mouth.

I stood rooted to the spot, unable to act, and frustrated with my small self for being in such a state. On the one hand, I wanted to be with my grandad, enjoy his attention, have him laugh at me – something no one else did. And yet it also felt bad.

I

felt bad. But how could that be? He was Pops. Why on earth would he want to hurt me? He loved me.

I simply couldn’t understand why I should so mind him tickling me, and wished I was not so pathetic and small. If I was bigger, I thought, it would all be all right. I glanced, as I always did, at my mother. Why was I so silly about Grandpops touching me?

She

knew what he was doing – she could see it for herself – and if

she

thought it was okay, why didn’t I? This is what grandads did, didn’t they? They tickled you, all over, until it hurt. I felt upset when I thought about it, wanted to burst out crying, but I didn’t. I felt bad that I didn’t like it, and also sad about my mother. How badly I wished I could explain how I felt or, better still, that she somehow just knew what was happening and stopped it, without me having to say anything. But once again I reminded myself, this was what grandads were for. Grandads tickled, and all children liked being tickled. So it must be

my

problem, mustn’t it? Must be

me

that was the problem. Why on earth did it make me feel so strange and bad?

Eventually, my anxiety overcome by my reasoning, I edged out from behind the door and walked to where Grandpops stood by my mother. I stretched my arm out as far as it would go so I didn’t have to go too close.

‘There,’ he said, holding the sweets out. ‘That’s it. Come here, come on, that’s it. Come closer so you can reach. Which one would you like? This one? Come on, that’s it.’

I moved a little closer with my arm outstretched, keen to maintain my distance, already aware that the sound of his breathing was changing. But I was too late in noticing, and before I could escape, he had grabbed hold of my wrist and pulled me against him, hard between his legs, crossing one of his legs over me so that I was clamped and couldn’t get away. The precious sweets, suddenly, were returned to his pocket, and his hands were now all over my chest, the stench of his breath wafting all round me. He was also now making the horrible scary noise he always made when he was tickling me, a sort of humming or buzzing, between tightly clenched teeth.

Within seconds I was lifted up and carried into the sitting room, to the chair he usually sat in, and placed upon his lap. Now his hands, always dextrous in containing my attempts to escape him, were moving all over me – up inside my skirt and then down my top, back up my top, and then down and then back up my skirt, as he continued to make the awful scary noise.

Sometimes, my mother, who was almost always there – either still making tea, or standing watching in the doorway – would say tiredly, ‘Oh, leave her alone, Dad, for goodness’ sake.’ But she never said it in a way that convinced me she meant it, and he never took any notice of her anyway.

Right now, she said nothing, and he lifted me up and turned me round, so that we were now face to face, my legs between his legs, pressed tightly against him, my feet hardly touching the floor. He began tickling me, again and again, all over, his touch, always firm, became rougher and more frantic, his face close to mine, his eyes never leaving my bewildered face.

And then suddenly, just as I thought I was going to suffocate, it stopped. Pops looked breathless and was hot. The horrible noise had stopped too. He pushed a hand into his pocket and sweets appeared again.

‘Go on,’ he said hoarsely. ‘Which ones do you want?’ And I duly chose the Fruit Gums, took the packet, and walked away, feeling a terrible sadness and a great need to cry. I didn’t know why, I just did. My mother brought him his tea then, and they continued to chat, as if nothing of importance had taken place.

I ate the sweets, because the sweets were the thing I most wanted, yet I felt sick and hungry, but full at the same time – as if something solid was lodged at the back of my throat.

I looked again at my mother, but she had nothing to say. She’d just stood there watching him, laughing.

HAPTER 2

Nowadays I take the view that my biological parents are only my parents because I chose them. Chose them to conceive me, to prevent anyone else having to have them – though I use the term ‘parents’ loosely I was never ‘parented’ as such.

I also now know that my life probably began as a result of my father raping my mother. When I was older, she told me she didn’t care for sex, but that my father, as in all his dealings with the world, wouldn’t take no for an answer. If she didn’t want sex, and most of the time she said she didn’t, then he’d simply shout and threaten until she submitted. I was conceived in this fashion when my brother Phillip was six months old and my sister Susan – their first-born – just two. If my conception was inauspicious, the pregnancy was worse – at some point before my birth my brother developed gastroenteritis, was hospitalized, and nearly died. Naturally, the very last thing my mother wanted, she later told me, was another baby. Particularly a girl.