I Think You'll Find It's a Bit More Complicated Than That (18 page)

Read I Think You'll Find It's a Bit More Complicated Than That Online

Authors: Ben Goldacre

What does all this tell us about peer review? The editor of

Medical Hypotheses

,

Bruce Charlton, has repeatedly argued

– very reasonably – that the academic world benefits from having journals with different editorial models, that peer review can censor provocative ideas, and that scientists should be free to pontificate in their internal professional literature. But there are blogs where Aids dissidents, or anyone, can pontificate wildly and to their colleagues: from journals we expect a little more.

Twenty academics and others have now

written to Medline

, requesting that

Medical Hypotheses

should be removed from its index. Aids denialism in South Africa has been responsible for the unnecessary

deaths of an estimated

330,000 people

. You can do peer review well, or badly. You can follow the single-editor model well, or foolishly. This article was plainly foolish.

Observations on

the Classification of Idiots

Guardian

, 18 August 2007

Every now and then something comes along which is so bonkers and so unhinged that it unmoors itself from all cultural anchoring points, and floats off into a baffling universe all of its own. I am an enthusiast for bad ideas, but nothing prepared me for this, in the academic journal

Medical Hypotheses

: an article called ‘Down Subjects and Oriental Population Share Several Specific Attitudes and Characteristics’.

You’d be right to experience a shudder of nervousness at the title alone, since this is an academic journal, from 2007, and not 1866, when John Langdon Down wrote his classic ‘Observations on the Ethnic Classification of Idiots’. That paper was the first to describe Down’s syndrome (which Down called ‘mongolism’), and in it the author explained that different forms of genetic disorder were in fact evolutionary regressions to what he viewed as the less advanced, non-white forms of humanity. He described an Ethiopian form of ‘idiot’, a mongoloid form, and so on. Looking back, it reads as spectacularly offensive.

Now. People with Down’s syndrome – who have three copies of chromosome 21, learning difficulties and other congenital health problems – do indeed look, to Westerners, a tiny bit like people from East Asia. This is because they have something called an ‘epicanthic fold’, a piece of skin that joins the upper part of the nose to the inner part of the eyebrow. It makes the eyes almond-shaped. You’ll find epicanthic folds on faces from East Asia, South-East Asia, and some West Africans and Native Americans. People with Down’s syndrome have various other incidental anatomical differences too, if you’re interested, such as a single crease in their palm.

Flash forward to 2007 – I think that’s where we are – to two Italian doctors. They offer their theory that the parallels between Down’s syndrome and ‘Oriental’ people go beyond this fleeting facial similarity. What is the evidence they have amassed? I offer it almost in its totality.

One aspect, they say, is alimentary characteristics. ‘Down subjects adore having several dishes displayed on the table, and have a propensity for food which is rich in monosodium glutamate.’

I, too, adore having several dishes displayed upon the table.

Two doctors, in an academic journal, in 2007, go on: ‘The tendencies of Down subjects to carry out recreative-rehabilitative activities, such as embroidery, wicker-working, ceramics, book-binding, etc., that is renowned, remind [us of] the Chinese hand-crafts, which need a notable ability, such as Chinese vases, or the use of chopsticks employed for eating by Asiatic populations.’

Perhaps you can think of cultural rather than genetic explanations for these observations.

There’s more. ‘Down persons during waiting periods, when they get tired of standing up straight, crouch, squatting down, reminding us of the “squatting” position … They remain in this position for several minutes and only to rest themselves.’ Amazing. ‘This position is the same taken by the Vietnamese, the Thai, the Cambodian, the Chinese, while they are waiting at a bus stop, for instance, or while they are chatting.’

And that’s not all. ‘There is another pose taken by Down subjects while they are sitting on a chair: they sit with their legs crossed while they are eating, writing, watching TV, as the Oriental peoples do.’

To me – and I may be wrong – this article is so fantastical, so ridiculous, and so thoughtlessly crass, that it’s hard to experience anything like outrage. But it appears in a proper academic journal, published by Elsevier, with a respectable ‘impact factor’ – a measure of how frequently a journal is cited – of 1.299. I contacted the editor. He told me the paper was a very short, discursive and preliminary communication, floating a general idea for discussion and debate, and that taking scientific ideas out of their context could be misleading. I hope I am not misleading anybody. I contacted Elsevier, the journal publisher: they will consider making the article free to access, so that anyone can read it for themselves. You can reach your own conclusions.

Guardian

, 4 October 2008

Important and timely news from the journal

Medical Hypotheses

this week: ejaculating could be ‘a

potential treatment of nasal congestion

in mature males’. My reason for bothering you with this will become clear later.

The first thing to note is that this is not an entirely ludicrous idea, but it is a tenuous one. Most decongestant pills work by increasing the activity in something called the ‘sympathetic nervous system’, which is involved in lots of largely automatic things in the body, like sweating, blood pressure and pupil size, as well as the ‘fight or flight’ mechanism. More activity in the sympathetic system causes the vessels of the nasal mucosa to constrict, reducing their volume and so clearing the blockage; but these pills can also have lots of fairly unpleasant side effects, because they tend to affect the whole of the sympathetic nervous system.

The argument from Dr Zarrintan is as follows. ‘The emission phase of ejaculation is under the control of the sympathetic nervous system … ejaculation will stimulate adrenergic receptors … and stimulation of your adrenergic receptors will give you relief from your cold.’ It’s a chain of reasoning that would make a nutritionist blush, and it has already been responded to by a letter entitled ‘Ejaculation as a treatment for nasal congestion in men is inconvenient,

unreliable and potentially hazardous

’. This response explains that ejaculation increases blood pressure and heart rate, which has its own side effects, increases androgens in the body which could increase prostate cancer, and so on. I honestly don’t know who’s kidding any more.

Now, I genuinely love

Medical Hypotheses

, published by Elsevier. Last year, you will remember, it carried an almost

surreally crass paper

in which two Italian doctors argued that ‘mongoloid’ really was an appropriate term for people with Down’s syndrome after all, because such people share many characteristics with Oriental populations.

Its articles are routinely quoted with great authority in the output of anti-vaccination conspiracy theorists, miracle-cure marketers and other interesting characters, but it also prints some interesting stuff. In that sense it serves a useful purpose, but it also acts as an extreme example of something we should all be aware of: you’re not supposed to take everything in an academic journal as read, final and valid.

I once had a conversation with

Medical Hypotheses

’ editor, Dr Bruce Charlton, and he raised two excellent points on the value of publishing loopy papers (that’s my phrasing – you can read

more from him online

). The first was that academics must be free to simply get on and publish things that outsiders might find weird, or misinterpret, without worrying about what the wider public might think.

The Downs paper above was simply uninformative and offensive, pushing this argument to the limit, but excepting such cases, his is a view I would heartily endorse. Academics should be free to write tenuous papers. The infamous 1998

Lancet

MMR paper is a perfect example. It described the experiences of twelve children with autism and some bowel problems, who’d had the MMR vaccine. This didn’t tell us much about the chances of MMR causing autism. But nobody should censor themselves from publishing such work, that might be of tenuous use or interest to somebody somewhere, on the off-chance that doing so might trigger a ten-year-long epic scare story from mischievous journalists. (We now know, much later, that the contents of that

Lancet

article were themselves the result of scientific misconduct; this is a separate issue.)

But Charlton also raises a more interesting point. He feels that the ideas market requires a diverse range of publication venues, so his journal is deliberately not ‘peer-reviewed’: the process whereby the great and the good look at your article and decide if it is worth publishing, or is methodologically flawed. Peer review is a system that has worked OK, to an extent, to stop outright nonsense appearing in very competitive high-quality journals; but it is also riddled with holes, it acts as no bar to nonsense being published in obscure peer-reviewed journals (where the bar is much lower), and it’s vulnerable to bullying and corruption.

Charlton’s journal publishes ideas rather than data. But we have to accept that a large amount of bad-quality data is being published in the 5,000 medical academic journals that already exist (printing fifteen million papers to date), and in many respects we have to hope that this situation will get even worse. In a recent column I described how

only one in four

cancer trials is actually published. There are widespread demands that all negative findings must be published, so that they are at least accessible, but this will often mean that inadequately analysed data from less competent studies are placed in repositories, or published in journals that will take very poor-quality papers.

The signal-to-noise ratio in the scientific literature is getting ever lower, and the simple fact that something has been ‘published’ is losing its currency as a badge of quality. That may, paradoxically, not be a bad thing. Academic papers are filled with ideas and evidence to be read, weighed up, and critically appraised, by people with the motivation and skills to do so, whoever they may be. Science is not, and should not be, about arguing from authority. The idea that the conclusions of a published paper are automatically true was never helpful. The academic literature is a buyer-beware environment.

If You Want

to Be Trusted More: Claim Less

Guardian

, 8 January 2009

‘Public Sector Pay Races Ahead in a Recession’, shouted the front page of this week’s

Sunday Times

. ‘Public sector workers earn 7 per cent more on average than their peers in the private sector – a pay gulf that has more than doubled since the recession began.’ The

Telegraph

followed up with a

copycat story

a few hours later.

In reality, this is one of those interesting areas where anybody who makes a firm statement is wrong, because there is not sufficient evidence to make a confident assertion in either direction.

The

Sunday Times

has identified a difference in the median pay of all public sector employees in the country, when compared with all the private sector employees in the country. It has then over-extrapolated from these two figures to claim that – job for job – public sector employees are paid more than their peers in the private sector.

We will discuss why that analysis is worse than useless in a moment.

But first, some interesting details. For its analysis the

Sunday Times

uses ‘annual salary’ instead of ‘hourly pay’, although the latter is clearly more meaningful, especially since the newspaper quotes the annual salary figures for part-time and full-time employees, all mixed together, but 31 per cent of public sector jobs are part-time, against 23 per cent of private sector jobs. In fact, quoting ‘hourly salary’ would also have made the difference between the public and private sector median wages look even bigger. So why did the

Sunday Times

and the

Telegraph

use annual pay?

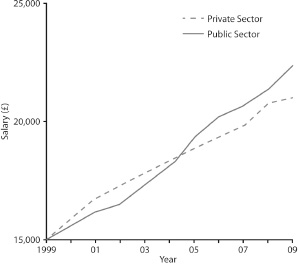

Perhaps because this figure makes the difference in medians look like a new phenomenon under the present Labour government. Using the hourly figures, you can see that public sector median hourly pay has been higher than private sector pay for years. If you go to the ‘Annual

Survey of Hours and Earnings

’ data on the ONS website which the

Sunday Times

used, you can see for yourself. It was £7.98 vs £6.72 in 1997 under the previous (Conservative) government, a difference of almost 20 per cent, and £8.56 vs £7.32 in 1999. Meanwhile, the ‘annual salary’ difference which the

Sunday Times

chose to use was negligible in 1999 (the first year ONS gave this figure), at £15,002 vs £14,963, a difference of 0.3 per cent, allowing the paper to create the illusion of a brand-new phenomenon: