I, Coriander (27 page)

Authors: Sally Gardner

Tags: #Juvenile Fiction, #Historical, #Europe, #General

‘I just meant...’ he said, somewhat flustered by my answer.

‘I know perfectly well what you mean,’ I said. ‘You wish me to look like myself and yet be someone else. I cannot do it. I have had my name taken from me once before. I had to fight to get it back. My name is Coriander. I am not the Ann you are looking for.’

‘I suggest,’ said Edmund, ‘that you reflect on my offer before making a hasty decision which you may come to regret.’

‘My answer, sir, is no.’

Danes saved me. She bustled into the study, unaware of Edmund’s presence.

‘We really must be going, my sparrow. The barge is waiting to take us to the bridge. We do not want to miss a moment of this wonderful day.’

‘Really, madam,’ said Edmund sharply, ‘should you not knock before you come in? This is not a barn.’

Danes looked surprised to be spoken to in such a manner. I thought she was about to give him a piece of her mind when Gabriel came in.

‘Come on, sweet mistresses. Everyone is waiting for you. Do you need a ride, sir?’ he said, on seeing Edmund.

‘Pray, is there no privacy in this house?’ said Edmund, ignoring him.

I took Danes’s arm and left the room, feeling like a canary newly released from its cage. We went down the steps to the water gate where everyone, including Hester with baby Joseph, was waiting in the barge.

I could not help remembering the day that Gabriel and I had come here to face Maud and Arise. Gabriel looked at me as if we were both thinking the same thing, and he smiled at me and squeezed my hand.

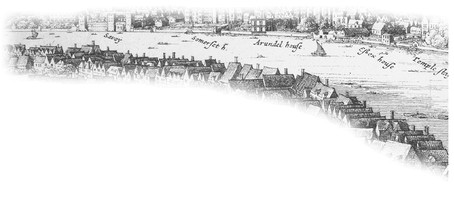

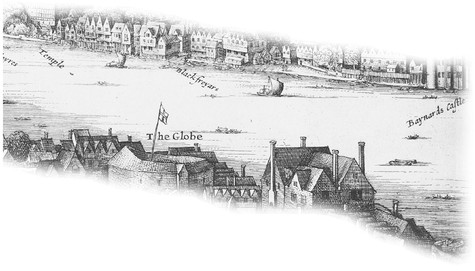

As we came out of the gates into bright sunshine the Thames had never looked more festive. Every boat, barge and ferry was bedecked with ribbons and flowers. People were singing and waving as if the whole of London was acquainted and I felt a surge of excitement. I knew that something extraordinary was about to happen.

We landed at the steps beside the bridge and joined the throng of people, all trying to get the best position to see the royal procession. We pushed our way through the crowds until we reached Master Thankless’s shop. Nell was waiting for us.

‘I am so pleased to see you,’ she said. ‘You would not believe how many people have offered good coin to join our party, for we will have such a fine view from here.’

‘I hope you turned them all away,’ said Danes, concerned.

‘Of course I did,’ laughed Nell, standing by the shop door like a guard dog. ‘Just look at the street, the way it is strewn with flowers! Can you believe that we are really going to see His Majesty? I think I may faint when he passes.’

The shop looked quite different. All the bolts of cloth had been cleared away and on the counter roast ham, beef, chicken, pies, sweetmeats, oranges and the first strawberries of the season had been laid out.

‘What do you think of that?’ said Nell proudly.

‘I think,’ said Gabriel, ‘that it looks like for a feast fit for a king.’

Master Thankless came to greet us with glasses of champagne. We were a very merry party and from the upstairs window the view down Bridge Street could not have been better. We could see everything. Down below, the crowds were packed tight. People were climbing out of windows and sitting on rooftops so that they might catch a glimpse of the royal procession. The bridge itself was hung with cloths of gold and windows were draped with silver tapestries. Everything shone in the morning sunlight.

‘When Oliver Cromwell entered the City, no one threw flowers in his path,’ said Danes, taking care not to call him Old Noll for fear of upsetting Ned.

‘I remember it well,’ said Master Thankless. ‘We were fair terrified in case the army took a fancy to killing any Londoners they met on their way. Now look how the tide has turned.’

We had to wait a long while to see the King, but when he reached Traitors’ Gate we heard a great shout go up from the crowd, so that even before we saw him we knew he was coming.

What can I tell you about the moment the King appeared? We leant out of the window to wave and cheer. I thought he looked magical, all dressed in white and gold, with his long dark hair and handsome face, smiling as he turned this way and that to acknowledge his subjects. Hester held up the baby, Danes wept and Nell had to be held back for fear of falling out of the window, so keen was she to touch the King. Such was the emotion that even Ned, a Puritan to his very toes, looked pleased.

Suddenly I felt a strange sensation. Everything went out of focus. All I could see was the King on his great white charger. I gazed at the horse as if transfixed. His mane and coat shone bright, as if lit up from within by moonshine, and as I watched he shook his head and stared straight into my eyes. My heart raced. Could it be so? Was such a thing possible? I hardly dared whisper the thought to myself.

Then, just as swiftly, all was as it had been before: the bells, the noise, the cheering, the procession, the King and his horse passing by.

‘Are you all right, Coriander?’ said Danes. ‘You look as if you have seen a ghost.’

‘Excuse me. I need some air,’ I said.

‘Come closer to the window,’ said Ned, stepping aside.

‘No thank you. I will go downstairs.’ I left the chamber quickly. I had the clear feeling that I must get back to my house.

I opened the shop door to find Edmund standing there barring my way. He took hold of my arm and moved me back into the shop, closing the door firmly behind him.

‘As you know, I have spoken to your father. My family are with Alderman Harcourt and wish me to escort you to them so that we may make our announcement.’

‘I need air,’ I said as I tried to pass him.

He caught hold of me. ‘I can see that my proposal came as a surprise to you.’

I looked at him, amazed. ‘Sir, can you not understand that I care nothing for you? I will never marry you. Never.’

‘I think you will live to regret your decision,’ said Edmund coldly, holding on to my arm all the tighter.

I pulled myself free. ‘Leave me alone. You are a fool, Edmund Bedwell,’ I said, and I picked up my skirts and ran out into the throng of people. I could hear Edmund behind me as I twisted and turned, finally losing him. The crowds pressed on me like shoals of fishes, the noise deafening. I passed maypoles and merrymakers, all dressed in their best and all in high spirits. I was certain that I saw Medlar, his lantern bobbing along. Then he was gone, as the cry went up, ‘The fountains are running with wine!’ and the noise blew like the wind over and into the crowd who surged forward in response.

I ran and ran, forcing myself onward. I stopped at the garden gate, my heart thumping in my chest. I straightened out my skirt and pulled down my bodice. My hair having come undone, I reached up to pin back the heavy ringlets. ‘Please let me not be wrong,’ I said out loud. ‘Please!’ Trembling, I lifted the latch.

For a moment I thought it was nothing more than a trick of the light or a tear in my eye, for my mother’s garden was alight with colour, brighter than it had ever been before. The rosemary, the thyme, the coriander, the mint, the roses, the marigolds and lavender shimmered like jewels. I ran my hand through the flowers and as I did so butterflies rose up and fluttered towards the sun, beating their wings in tune with my heart.

The garden seemed empty but then I turned and looked at the door to my house. There on the steps he stood, glimmering as if in a heat haze. Fearful that my eyes might be deceiving me, I walked slowly up the path towards him.

He came into focus. Tycho! There was Tycho.

‘You came!’

He took my face in his hands.

‘Coriander, how could I lose you? You are my shadow. You are my light. Will you be mine, Coriander?’

I threw my arms around him and in that moment I knew that this world and the world beneath the silvery mirror had become one, all was well and the future was ours for the taking.

D

awn is breaking and the watchman is calling in the new day. My tale is told, written not by this world’s hourglass. With this, I blow out the last candle.

I

f we shadows have offended,

T

hink but this and all is mended:

T

hat you have but slumbered here,

W

hile these visions did appear.

William Shakespeare

A Midsummer Night’s Dream

Some Historical Background

T

his story is set in the period of the Commonwealth, after the Royalists had lost the Civil War and King Charles I had been executed at Whitehall in January 1649. It was the time of a great experiment - England’s one attempt to get rid of the monarchy and become a republic - and what happened in the 1640s and 50s made Parliament and the monarchy what they are today.

It is hard for us to understand how shocked people were by the execution of the King. Up to that point it was believed that the monarch was there by divine right, chosen by God to rule over His people and to be Head of the Church of England. Charles I believed completely in the divine right of kings. He was married to a Roman Catholic Queen, which did not make him popular. He was not a good politician or a wise ruler, and he made many bad and foolish decisions that ultimately led to the start of the Civil War.

The Civil War brought bitter and bloody battles that divided families and neighbours, spoilt the land and caused great suffering and even starvation among the people. There were two camps, Royalists, who supported the King, and Puritans (also known as Roundheads because of their cropped hair). The Puritans were strong Protestants who desired to reform the Church of England and prevent it from falling back into the arms of the Roman Catholic Church. They believed that only the Bible represented the authority of God, and that Sunday should be kept for prayer and the singing of Psalms. Activities such as dancing, acting, singing and playing music were thought frivolous. Oliver Cromwell was their great champion and general of their army, called the New Model Army.

The Civil War ended with the execution of the King. There followed ten years of the Commonwealth under the leadership of Oliver Cromwell. Cromwell closed all the playhouses and banned Christmas and Christmas pudding. Maypoles were not allowed, and anyone not attending church was fined. Many old churches were ransacked, their stained glass windows broken, and religious relics burnt, for worship was to be kept simple.

All sorts of radical Protestant sects suddenly emerged: the Levellers, the Ranters, the Quakers, the Diggers and many more, some more extreme in their beliefs than others. Among them were the Fifth Monarchists. They were fundamentalists, and believed that England had to be cleared of all its sinners. Only then would the fifth reign be established, that of Lord Jesus Christ, who would come to take up the crown of England. For a time they held great political sway, but in the end even Oliver Cromwell found their demands too far-fetched and would no longer entertain them.

London was relatively untouched by the Civil War, mainly because the King abandoned his capital for Oxford. Then, when it looked as if Cromwell was going to win the war, it was sensibly decided not to close the gates of London Bridge but to allow him to come in unchallenged.