How to Teach Your Children Shakespeare (17 page)

Read How to Teach Your Children Shakespeare Online

Authors: Ken Ludwig

Tags: #Education, #Teaching Methods & Materials, #Arts & Humanities, #Literary Criticism, #Shakespeare, #Language Arts & Disciplines, #General

Quotation Page Reminder

Please remember that as your children memorize these and the other passages in this book, they should have the Quotation Pages in front of them. While some of these passages (Passage 9, for example) aren’t difficult to memorize because of their length and content, the current passage

is much more complex, and the Quotation Pages will help your children

enormously

with memorizing it. Let’s look at one of the Quotation Pages for the current passage as an example:

VIOLA/CESARIO

My father had a daughter loved a man

As it might be

,

perhaps

,

were I a woman

,

I should your lordship

.

ORSINO

And what’s her history?

VIOLA/CESARIO

A blank, my lord

.

She never told her love

,

But let concealment

like a worm i’ th’ bud

,

Feed on her damask cheek

.

The Quotation Pages simplify the process in a number of ways. First, just by being in large, distinctive print, they make the words less daunting. Second, they separate the sentences and thoughts onto different pages, so

that your children memorize the passage in accessible chunks. Third, each page contains formatting that makes each sentence easy and logical. For example, on the first page, by isolating the word

perhaps

, it reminds us to pause, which simplifies what is otherwise a very complex sentence.

So don’t forget to go to

howtoteachyourchildrenshakespeare.com

to print out the Quotation Pages for all the passages in the book. Then—you know the drill: quiet room, no embarrassment, out loud, repetition. I’ll remind you only one more time, later in the book, when you’re least expecting it.

Passage 11

Do Not Embrace Me

ORSINO

One face, one voice, one habit, and two persons!

A natural perspective, that is and is not!

ANTONIO

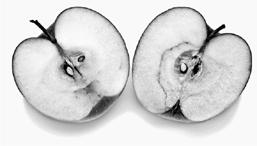

An apple cleft in two is not more twin

Than these two creatures. Which is Sebastian?

OLIVIA

Most wonderful!

VIOLA

If nothing lets to make us happy both

But this my masculine usurped attire

,

Do not embrace me till each circumstance

Of place, time, fortune, do cohere and jump

That I am Viola

.

(

Twelfth Night

, Act V, Scene 1, lines 226 ff.)

T

his passage never fails to raise a lump in my throat. To understand why it is so touching requires some background. It occurs in the final scene of the play and pulls everything in the Viola Plot together.

Up to this point, a great deal of confusion has been caused by Sebastian’s arrival in Illyria. Sebastian, as you know, is Viola’s twin brother, and each sibling thinks the other was drowned in a shipwreck. Because Sebastian and Viola look identical, they get taken for each other by all the other characters in the play.

In the final scene, Shakespeare brings all the characters together onstage, raises the confusion to a dizzying height, then resolves all the plotlines at the same time. The scene begins with Orsino and Cesario arriving at Olivia’s estate. Then, one after another, Antonio, Olivia, Sir Toby, and Sir Andrew arrive, and each has a different story about the treachery of this boy Cesario. Finally, when the confusion has reached a fever pitch, Shakespeare brings Sebastian onto the scene—and suddenly there are two identical human beings on the stage together. Identical. You can’t tell them apart.

At which point, everything stops dead.

No one moves.

Then Orsino exclaims:

One face, one voice, one habit

[outfit],

and two persons!

A natural perspective, that is and is not!

In those days, a

perspective

was an optical device made with mirrors that helped artists see visual scenes in proper proportions; and so a

natural perspective

means an optical illusion created naturally without mirrors. And now we have a list:

face

,

voice

,

habit

,

persons

.

Repeat it with your children over and over.

face

,

voice

,

habit

,

persons

.

One face, one voice, one habit, and two persons!

A natural perspective, that is and is not!

Then Antonio says:

How have you made division of yourself?

An apple cleft in two is not more twin

Than these two creatures. Which is Sebastian?

Antonio is reminding us as clearly as possible that the two creatures in front of him look absolutely identical. Orsino has just said it with his

one face, one voice

speech, and Antonio repeats the idea:

An apple cleft in two is not more twin

Than these two creatures

.

Which is Sebastian?

An apple cleft in two

(photo credit 19.1)

Shakespeare does not repeat things idly. He is doing it for a reason. In any live production, the two actors in front of us will not actually look identical. They will probably not be related in real life, and even if they were—even if they were twins—they wouldn’t be identical because twins of different sexes are never identical. However, we, the audience, must imagine that they look identical because the other characters onstage are seeing them that way. And in order to make the audience believe that they are identical, Shakespeare has his characters say it twice.

And now comes what is usually the biggest laugh in the whole play. Olivia has just become betrothed to Sebastian, and she’s crazy about him. Now, suddenly, from her point of view, there are

two

Sebastians. Her life is about to become doubly happy and pleasurable. So what does she cry?

Most wonderful!

At this point, Viola and Sebastian see each other. In the theater, this moment can, and should, be electrifying. The whole play has been moving toward this moment from the beginning. The first to speak is Sebastian:

SEBASTIAN

Do I stand there? I never had a brother

,

Nor can there be that deity in my nature

Of here and everywhere. I had a sister

,

Whom the blind waves and surges have devoured

.

Of charity, what kin are you to me?

What countryman? What name? What parentage?…

Were you a woman, as the rest goes even

,

I should my tears let fall upon your cheek

And say “Thrice welcome, drownèd Viola.”

This is a tricky passage to understand, so let’s parse it out together for your children. I want them to be able to recite it and understand it before we’re through. (They needn’t memorize it.)

Do I stand there? I never had a brother

,

Nor can there be that deity in my nature

Of here and everywhere

.

Deity

here means “godliness.” So Sebastian is saying: “There is nothing in my nature that is like a god, so therefore I can’t split myself in two and be both here and over there at the same time!”

I had a sister

,

Whom the blind waves and surges have devoured

.

The

blind waves and surges

are the watery storm that capsized the ship. Equally,

devoured

is a wonderful word in this context. If Shakespeare had used

drowned

instead, it would not have filled out the metrical line as well and would not have been as powerful.

Sebastian continues:

Of charity

[out of charity],

what kin are you to me?

What countryman? What name? What parentage?…

Were you a woman, as the rest goes even

,

I should my tears let fall upon your cheek

And say “Thrice welcome, drownèd Viola.”

Sebastian is doing a lot of talking here when, logically, he would take one look at his long-lost sister, run to her, and throw his arms around her. But there is something bigger going on. Shakespeare is doing something that all writers try to do effectively: He is pulling the string.

PULLING THE STRING?

What I mean is that Shakespeare is stretching out the conclusion for as long as possible until the final revelation. By this time in the story, Sebastian would realize in any normal sense of reality that this person standing in front of him is his sister. He has adored her since they were children. He knows exactly what she looks like. At most she’s wearing trousers and a shirt and has her hair pinned up under a cap. Otherwise it’s good old Viola. But Shakespeare doesn’t let Sebastian verbalize that realization until lines and lines of poetry have gone by. (I have cut the passage down for purposes of discussion. In fact, there are forty-six lines from the moment Sebastian enters until Viola cries

I am Viola

.) Shakespeare holds it off because we, as the audience, receive a sort of exquisite pleasure by having to wait for it. We see this phenomenon frequently in the movies. We’ve known from the beginning that the two gorgeous leads will end up together, but the writer holds off the final explosion of joy until the last possible second because that’s what romantic comedy is all about. It’s the same with romantic novels. In Jane Austen’s

Emma

, will Emma and Mr. Knightley get together at the end? Of course they will, but that’s the beauty of a good love story: The author holds off the final partnering until the last possible moment.