How to Raise the Perfect Dog (11 page)

Read How to Raise the Perfect Dog Online

Authors: Cesar Millan

Tags: #Dogs - Training, #Training, #Pets, #Human-animal communication, #Dogs - Care, #General, #Dogs - General, #health, #Behavior, #Dogs

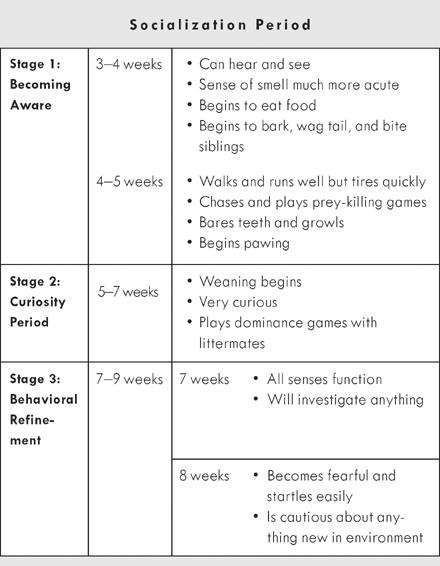

When her pups are about six to seven weeks of age, a mother dog begins to be a little less possessive of them and lets other members of the pack help lessen her workload. Among packs of wild canines, the rearing of the young is truly a family affair. Sometimes adults other than the mother even share the job of feeding the maturing pups, returning from hunts and regurgitating food for them. More important, the whole pack always shares in the education of the pups, including disciplining them. The adult dogs work together to form what amounts to an amazing, comprehensive, and cooperative “public school system,” to build a healthy, productive new generation. If another adult member of the pack feels the pups are getting a little too boisterous in their play, she may use physical touch—a nudge, or even a firm but nonaggressive bite—to communicate. If an adult or adolescent senses a pup doesn’t understand the manners of the dinner table, she may emit a low growl to warn the pups away from her food. Every dog recognizes that having obedient, well-adjusted, socially literate puppies is necessary for the survival of the entire pack.

However, domestic dogs don’t live only with dogs; they live with and must rely on us humans. In a way, your puppy needs to grow up “bilingual”—speaking the languages of both dog and human—before he can go out into the world. Tens, maybe hundreds of thousands, of years of evolving with us side by side have given our dogs an inborn proficiency in understanding our energy and body language, a proficiency that is just as impressive as that of our closest evolutionary cousins, the other primates. Nevertheless, being domesticated doesn’t bring automatic understanding. “Human” is still very much a second language to puppies. To become good pets, puppies need positive interactions with humans on a daily basis during the period between five weeks and nine weeks. They also need to be exposed to the different kinds of stimuli that await them out in the modernized world. That’s why a diligent breeder participates as actively as the canine mother during the socialization period of her puppies’ lives, to expose each puppy to different aspects of human culture and to introduce him to the oddities of the half dog-half human society into which he’s been born.

Diana Foster describes the routine she and her husband, Doug, go through with every German shepherd litter that they raise.

At about five weeks of age, we start bringing the puppies indoors one at a time, so we can get them used to being in the company of humans without their littermates. They’re so dependent on being with each other and being with the mother, when we first bring them in and put them down, they’ll start whining. So we’ll hold them for a little bit, then we put them back with the mother. It’s good to give them a little bit of stress so they learn how to handle it, but a few minutes a day is plenty. We do it in short increments, so the dog gets used to being away from the whelping box, and around people.

The Fosters also make sure their shepherd puppies continue being exposed to a series of new, real-life stimuli and stressors during this time:

We try to have them situated on the property where there’s the most commotion. We have five acres, but we never put them in the back pen or up on the hill where they can’t see everything that’s going on. Instead, we have a huge pen in the front, and that’s where we have a lot of people who pull up to come look at our dogs. The kids get out of the car screaming. There are other dogs barking. There’s music. There are my kennel workers. There’s the trash truck. Since we can’t take them out in public when they’re that young, we bring the environment to them, so when they hear a loud sound, or something scares them, they may go screaming to the back of the pen. I tell my kennel workers, “Do nothing. Don’t go over to them. Don’t talk to them. Don’t pick them up. Allow them to work it out for themselves.” And little by little, they start coming toward whatever made the noise and getting a little braver, and then they realize the big bad thing’s not going to hurt them, and then they’re fine. The less you do, the better. If I were to write a book about raising puppies at this age, I might even call it something like

Do Nothing!

Dogs also love routine, which is important for their development, both at this early stage and throughout their lives. Brooke Walker keeps a strict regime around her house when socializing her miniature schnauzer pups.

As soon as the grass dries if there’s morning dew, I’ll take them out in the yard. They all potty instantly. They get their breakfast. They stay out, they play. They go back for their nap. They come out. They get their lunch, they potty, they play. They go back in. It’s such a routine. I feed three times a day once the mother has stopped feeding. Normally, mothers feed for four weeks. Binky was an exceptionally involved mother; she fed and cleaned those babies straight through five weeks.

Brooke told me that I was the only person she ever let adopt one of her puppies before ten weeks. Usually, she likes to have the house-breaking and crate-training process completed by the time her puppies leave her home.

Housebreaking is easy. They come outside in the mornings and I praise them when they pee and poo outside. They come out, I praise. They go potty, I praise. Lots and lots of praise. My owners are always calling me to say that they are amazed their puppy came to them already housebroken. I also always have older dogs around, and they are just wonderful teachers; my puppies are so much wiser about the world by eight to ten weeks old because of the older dogs’ being such great examples for them to follow.

Diana Foster and Brooke Walker both crate-train during the socialization period, starting at about six weeks, after the puppies are weaned. That’s a very smart thing to do because, as we’ll see in the next chapter, the most difficult, most unnatural thing you’ll ever need to teach your dog is the skill of being alone without you or without his pack. By training a puppy to be alone for short periods of time in his crate while he’s still in the phase when the most basic blueprints of living are being etched into his brain, he learns that “alone time” is a part of his pack’s behavior—even though it is absolutely, totally foreign to a dog’s DNA.

“As they get a little older—more like seven or eight weeks—what I like to do is mix it up,” Diana explains.

Sometimes I’ll have them together as a litter. They’ll run around and play and sleep together, and then I like to separate them all. I’ll put each puppy in a little crate by himself, and I’ll put each one in a pen by himself. I start to get them used to that because I know once they go to a home, they’re not going to have each other to keep them company. We start with very short increments, like maybe half an hour. I’ll put them in the crates, and they’re all screaming. After ten or fifteen minutes, they all just go to sleep.

“There’s not a dog that leaves my house that doesn’t love a crate,” Brooke boasts. “I throw a treat into the back of the crate and say, ‘Do you want a cookie? Okay, it’s in your crate.’ So the crate becomes ‘Oh wow, this is my favorite spot anyhow, ‘cause I get a cookie when I go in there.’ I let them take their naps in there, then I let them out. I start with short periods of time, gradually getting longer. And so crate training is the easiest thing in the world to do.”

Exploring a Brave New World

Exploring a Brave New World

During the “behavioral refinement” phase, the puppies become bolder and strike out on their own into new areas. They want to investigate and explore absolutely everything. This is the time when serious breeders start exposing the puppies to as many new stimuli as possible. Brooke takes behavioral-enrichment play seriously—she wants to raise curious, intelligent, adaptable schnauzers, so she provides them with a huge selection of interesting toys and games to choose from.

My backyard is like Disneyland. I just love introducing them to this yard. They play on the patio, they play in the dirt; when they get courageous enough, they’ll explore the high grass I have growing in my garden, or they’ll explore inside my hedges. I teach them a lot of skills in their exercise area. Since they are terriers, they love to go into holes, so I provide carpeted cat tunnels for them to climb inside and run through. They love that, and when they get big enough, they climb to the top of them. I provide lots of different toys: pull toys so that they can pull against one another, toys with sounds or bells in them, different types of balls for them to chase, different things to stimulate them. I cycle between different toy combinations every single day.

Says Diana Foster of her German shepherd pups,

At this point, they don’t need the mother for survival anymore, but we like to keep them with her as long as possible, because of the natural way she disciplines them. For instance, she tells them not to touch her bone or stops them if they start getting too rough with her. Her correction is quick. The puppy may yelp and run away with his tail tucked. And what does the average person do? Pick them up. “Oh, you poor thing. Come here!” Everyone wants to rescue them and feel sorry for them when anything new happens. What they’re doing is reinforcing the fact that something bad just happened. But in their world, what happened wasn’t bad! It was just a learning experience. Their real mother couldn’t care less. She allows the puppy to work out the situation on his own. That’s how he grows, that’s how he learns. He may run away whimpering, but after just a couple of seconds, he’s back playing with his friends. It’s not a big deal. It’s only a big deal to the humans. I’m like Cesar. I sit for hours and I just watch the dogs. And you can learn so much just by observing what they do, especially a really good mother.

Angel’s mom, Binky, was such a good mother that she remained involved with the disciplining of her pups right up until the day each one was adopted out. That’s an important part of the reason Angel was so alert and open to accepting rules and structure once he came to live with my family.

Early Socialization: The Cautious Phase

Early Socialization: The Cautious Phase

(Eight or Nine Weeks)

At around eight or nine weeks of age, a puppy usually hits a phase where he goes from being outgoing and recklessly curious to becoming extremely cautious again. This is to be expected, and in nature it’s a stage that passes quickly. The best breeders take special care at this age not to overprotect their puppies but instead help them to develop real self-confidence on their own. “I make sure my puppies are safe and not being bullied or harmed in any way by the rest of the pack,” says Brooke. “But to rescue a puppy every time will only lead to a very fearful dog. I want to prepare all my puppies for being gone from me, their siblings, and their mother. At eight weeks, I take my puppies to Fashion Island here in Newport, California. There are many colors, noises, and smells that they haven’t experienced before. There is a special fountain that pops up water from the ground in irregular sequences. Although schnauzers are not supposed to be water dogs, I have yet to have a puppy that didn’t get into that fountain and enjoy trying to catch the bubbles!”