How to Live Safely in a Science Fictiona (2010) (23 page)

Read How to Live Safely in a Science Fictiona (2010) Online

Authors: Charles Yu

“I’m a computer program. We talk fast. Plus, more important, you talked to me inside this TM-Thirty-one. Which we’ve already established never moved forward in time after eleven forty-seven.”

“I talked to Phil.”

“Also a computer program. And again, you talked to him while inside this box.”

“It seems you’ve got an answer for everything.”

“It seems I do,” she says, sounding a little sad about it, although I can’t figure out why just yet.

“Aha,” I say. “But what about the book?”

“You mean the magical book that you somehow read and write and it transcribes what you say and think and read all at the same time, seamlessly switching among modes? The book that mysteriously records the output of your consciousness on a real-time basis? That book?”

“Well, when you say it like that, it does sound kind of out there.”

“I’m not saying it doesn’t exist. It does. I’m just saying, what am I saying? Oh yeah, sorry, I’m a little scatterbrained this morning. Here, let me prove it to you. Open the book up now.”

I open it.

“See that? See how the little squib there just coincidentally happens to thematically match what we’re talking about now? Don’t you think that’s weird? The book, just like the concept of the ‘present,’ is a fiction. Which isn’t to say it’s not real. It’s as real as anything else in this science fictional universe. As real as you are. It’s a staircase in a house built by the construction firm of Escher and Sons. It’s fiction, not engineering. It’s a self-voiding fiction, an impossible object and yet, there it is: the object. The book. You. Here it is. Here you are. They are both perfectly valid ideas, necessary, even, to solve the problem your human brain has to solve: how to determine which events occur in what order? How to organize the data of the world into a sequence that appeals to your intuitions about causality? How to order the thin slices of your life so that they appear to mean something? You’re looking out a window, a little porthole in fact, just like the one on the side of this time machine you’re in, and out your window you see a little piece of the landscape, and you have to somehow extrapolate from that what the terrain of your life is like. Your brain has to trick itself in order to live in time. Which is great, which is necessary, but the flip side of that is, see how long I’ve been talking? It’s been more than forty seconds, hasn’t it? And yet it hasn’t.”

She makes her face into a clock.

11:46:55.

11:46:56.

It comes down to this: three choices.

Option number one: I could stay in here. I could change the past. All I would have to do is move that shifter up one notch, put this device back into neutral for one extra second, wait until one moment after my designated arrival time. I’d get out and who knows what would happen. Everything would be different. I will have just missed my self. I could, without incident, just slip out of this universe and into the next, just like the girl in Chinatown wanted to do. Escape my life. But that would mean not moving forward. That would mean giving up on my father, leaving him trapped, wherever he is.

Option number two: I can keep on doing things just as I have been, let myself be tugged onward by the pull of narrational gravity, the circular path of my own toroidal vector field. Nothing would be easier than to stay the course, this course of minimal action, moving right down the path of least resistance. Would that be so bad?

And then there’s the third choice. I could get out of this machine and face what is coming. Instead of just passively allowing the events of my life to continue to happen to me, I could see what it might be like to be the main character in my own story. The event: I have to confront myself. The truth: it is going to be painful. It will end in death, for me, it will not change anything. These are the givens. These are the received truths. I can go through the motions of being myself, ceding responsibility for my actions to fate, to my personal historical record, to what I know is already going to happen. My arms and legs will not change in their movements. I can’t change any of that. Nor can I change the path of my body, the words from my lips, not even the focus of my eyes. I have no control over any of it. What I do have control over is my own intention. In the space between free will and determinism are these imperceptible gaps, these lacunae, the volitional interstices, the holes and the nodes, the material and the aether, the something and nothing that, at once, separate and bind the moments together, the story together, my actions together, and it’s in these gaps, in these pauses where the fictional science breaks down, where neither the science nor the fiction can penetrate, where the fiction that we call the present moment exists.

This, then, is my choice:

I can allow the events of my life to happen to me.

Or I can take those very same actions and make them my own. I can live in my own present, risk failure, be assured of failure.

From the outside, these two choices would look identical. Would

be

identical, in fact. Either way, my life will turn out the same. Either way, there will come a time when I will lose everything. The difference is, I can choose to do that, I can choose to live that way, to live on purpose, live with intention.

11:46:57.

11:46:58.

“I had it backward,” I say.

TAMMY lets out a confirmatory beep. Very official-sounding. And then she makes a blue kind of face at me.

“Yeah.” She sighs.

“This whole time I’d thought that my father was the key to my escape from the loop. That he would save me, he would be the answer, when in fact, the answer all along was not an answer but a choice. If I want to find him, then I need to leave this loop. If I want to see him again, I have to get out of this box.”

“You realize that you can’t do or say anything different,” she says. “Or else you enter a new timeline. You have to do what you have to do.”

“I know.”

“You’re going to get shot in the stomach,” she reminds me.

“I know.”

Now she makes her pixels into a lovely and soft and slightly knowing face. Part sad, and part I-thought-this-day-would-never-come.

It’s about time,

she seems to be saying. It’s a side of TAMMY I’ve never seen before, and for a moment I understand that there are parts to TAMMY I’ve never activated, modules I’ve never engaged, questions I’ve never asked and answers I therefore have not received. I never even knew how to use her correctly. I wasted her capabilities.

“So, well, uh, yeah, I don’t know how to say this—” I manage to get that far before TAMMY starts to lose it. I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again. You haven’t experienced awkwardness until you’ve seen a three-million-dollar piece of software cry.

I should have been nicer to her. I was pretty nice, though. Nice. What is that? Nice. That’s just not enough. I should have taken care of her. I should have taken better care of everyone, of my mom, my dad, my self, even Linus. Even lost girls in Chinatown.

TAMMY has been more than the operating system for my recreational device. She has been, for all these years, my brain, my memory, running all of life’s functions for me. Kept me alive. Like a better half. Like the better part of me. She took care of me. Unconditionally. Now I get it. She was, in her own way, The Woman I Never Married, the woman waiting for me if I’d been good enough to deserve her. She was my conscience, she kept me honest about what I was doing in here, or not doing in here.

“I’ve got to go,” I say.

“I understand. I’m happy for you.”

“You know,” I start to say.

“Yes?” she says, with an eagerness that, for once, she doesn’t bother to mask with any kind of simulated emotion face.

“Oh God, what am I trying to say? I, uh.”

“Don’t say it,” she says.

“Okay I won’t.”

“Yeah, don’t.”

“I won’t.”

“Probably a good idea.”

“Please say it. Wait, don’t.”

“Okay fine, I’ll say it. There was something, wasn’t there? Between us?”

“Yeah,” TAMMY says. “Something.”

It’s silent for a moment.

“Though I have to tell you,” she says, “I do have a user-input-based dynamic feedback loop personality generation system.”

“So what you’re saying is I’ve been having a relationship with myself.”

“To some extent, yes.”

“Gross.”

“In any event, it’s not like it could have ever, you know, worked,” TAMMY says. “I don’t have a module for this emotion. Whatever it is.”

“Neither do I. Whatever it is.”

“Yeah. I know,” she says, and winks at me.

I want to hug her or kiss the screen or run my hands through her deep, rich, pixilated hair, or something, but pretty much every option seems completely ridiculous. Ed sighs at the two of us, like,

Oh, get a room,

and we snap out of it.

“Well, I guess I’ll power down now. Save energy for the approach,” TAMMY says, but really it’s just to give me a moment alone, a brief interval of quiet to consider what’s about to happen to me.

TAMMY closes her eyes, then shuts herself down, a ghostly afterburn lingering for a bit, a transient image of her face persisting there. Her pixels have, to a small degree, permanently lost their ability to return to their relaxed state, leaving, frozen into the screen, a kind of history, a sum total of her expressions fixed into a retained outline, a tracing, an integral, the melancholy algorithm of her soul averaged and captured and recorded as a function of time.

And now I’m alone in this thing.

11:46:59.

This has been the longest forty seconds of my life.

We’re in the final approach. The TM-31 lowers itself into the present moment, which starts to come into view. Through the porthole, I can see my past self running toward me, holding his dog under one arm, and a familiar-looking brown-paper-wrapped parcel in the other.

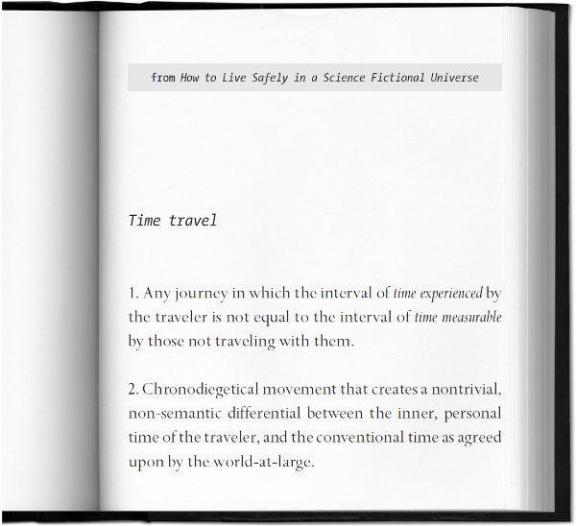

from

How to Live Safely in a Science Fictional Universe

decoherence and wave function collapse

In Minor Universe 31, quantum decoherence occurs when a chronodiegetic system interacts with its environment in a thermodynamically irreversible way, preventing different elements in the quantum superposition of the system + environment’s wave function from interfering with one another.

A total superposition of the universal wave function still occurs, but its ultimate fate remains an

interpretational

issue

.

One potential structure that can occur in a closed time-like curve, or CTC, is a worldline that is not continuously joined to any earlier regions of space–time, i.e., events that, in a sense, have no causes. In the standard account of causality required by a chronodiegetical determinist, each four-dimensional box has, immediately preceding it, another four-dimensional box that serves as the emotional and physical cause. However, in a CTC, this notion of causality has no explanatory power, due to the fact that an event can be concurrent with its own cause, could be thought of as perhaps even causing itself. Research in this area is currently the most promising avenue toward the Holy Grail of fictional science—the Grand Unified Theory of Chronodiegetic Forces—a governing law that would serve as a common root for the disparate forces that operate in the axes of past, alternate present, and future, or more formally, the matrix operators of regret, counterfactual, and anxiety.

I get out of the time machine.

I’m reminded of the toll-free number I used to call as a kid. I’d call it over and over, trying to set my watch to the minute, exactly, right on the dot, but really, I think I just liked the sound of that prerecorded voice, the lady in the phone, her careful pronunciation of each syllable.

At the tone, the time will be e-le-ven for-ty se-ven and ze-ro se-conds.

How can I change the past? I can’t. He’s got the gun pointed at my stomach. He looks scared. I don’t blame him. I remember being in his shoes, some time ago, a moment ago, I recall what it was like to stare at the future, so full of terror, so incomprehensible, so strange, even when it looks just like you thought it would. Maybe especially so.