How to Break a Terrorist (15 page)

Read How to Break a Terrorist Online

Authors: Matthew Alexander

A VISIT FROM THE BOSS

G

ENERAL GEORGE W. CASEY

sits quietly in the conference room for almost an hour as Randy summarizes the past few weeks. The breaks we’ve made have done serious damage to the networks around Baghdad. As a result, the number of suicide bombings in the second half of April have plummeted. Since the Baratha Mosque attack on April 7, where three suicide bombers killed at least seventy people, there have been no catastrophic attacks.

We’re making a difference, even if we haven’t made the final jump to Zarqawi yet.

At the end of the briefing General Casey says, “I have a question. Why do they join?”

Randy’s ready for the question. He gives the general the standard line. They want to establish a caliphate. They want a fundamentalist state and Sharia law. They want to use Mesopotamia as a base to attack the United States and Israel.

That’s not exactly right. I have the chance to influence the senior commander in Iraq and I want to say something.

I stand up. General Casey turns and looks at me. “Sir, that is true for some of the Al Qaida loyalists, but there is a distinction. Since coming here, I’ve seen many average Sunni who have joined Al Qaida out of economic need and out of fear.”

The general gives me an inquisitive look.

“Fear of the Shia militias, the Badr Corps, the Mahdi Army. After we invaded and disbanded the army, the Shia threw most of the Sunni out of work. Then they started moving into their neighborhoods, kidnapping and killing people. Many of our detainees joined Al Qaida simply to survive. They aren’t ideologues, and they don’t believe in Al Qaida’s dogma, but they see Al Qaida as the only entity willing to help them.”

I want to say: if we could only harness that, figure out a way to work with the Sunni so that they feel that we are protecting them, that we are their allies, most would turn against Al Qaida.

General Casey’s response to me is a dismissive, “Hmm.” I decide to keep my mouth shut. Randy’s already looking at me with bulging eyes.

So much for that. The meeting breaks up, and I head into the routine for the day. In a few days, I’ll lose Steve to an assignment at another station. I’ll cover down on Abu Raja and Naji, so by week’s end I’ll have my hands full. Meanwhile, Tom and Mary are busily working with Abu Bayda. Soon his son will leave for Abu Ghraib to be outprocessed, as will he. Abu Bayda will almost certainly hang. A senior Al Qaida leader cannot hope for much mercy in front of the court, no

matter how much information he provides. That said, perhaps his cooperation will buy him some leniency.

His son will be released. He has committed no crime other than being his father’s boy. His mother lives in Baghdad, and he will soon be able to return to her.

Naji and his older brother Jamal are still living in the storage room. We bring them extra treats and cups of hot cocoa whenever we get the chance. Meanwhile, we’re trying to track down their nearest relatives.

A SLIP

A

BU RAJA STARES

at me in complete surprise. His hands clutch the mask he’s just pulled off.

“Hello, I’m Matthew. Steve had to leave for a few days, so I’ll be talking with you.”

“Oh. Yes. Nice to meet you.” He regains his composure, but life in the cellblock has not been kind to this pediatrician. I thought he hit bottom last week, but he’s plunged even further. He’s aged since he’s been here, and his eyes betray hopelessness.

“I appreciate your willingness to cooperate with us.”

He sighs and recites, “Whatever I can do to help, Mister Matthew.”

“I’ve read the reports, so I know what you and Steve have discussed, but I did want to ask you a few questions.”

“Certainly.”

“Where did you say you grew up?”

“Mansur. My family is from Mansur,” he says bleakly.

“Has it been hard for you to work since the invasion?”

“Yes. After I lost my government job, it has been very hard.”

“It is a noble thing, what you do—taking care of sick children.”

I see the shreds of his pride well up above the despair for just a brief moment. “Thank you. It was my life’s work…once.”

He sounds wistful. Yearning. That gives me an idea.

“Abu Raja, if you could go back and do things over again, what would you do differently?”

He doesn’t even have to think about it. In fact, he looks as though he’s thought of only that since he got locked up.

“A few years ago, I received a job offer to work in Qatar. I turned it down…” His voice trails off. He fights his emotions. I wait.

“I…should have taken it. I should have moved my mother and myself to Qatar. We never would have come to this if I’d just taken that path.”

“Maybe you can still get to Qatar,” I say.

That barely registers on him.

“I can’t make promises, but I’ve seen others get out of Iraq. We have the power to do that. But it’s not easy to convince our boss.”

He looks even more miserable.

“What more can I tell you? I’ve admitted my role. I’ve admitted who I am. I’ve told you that I was at the farmhouse.”

“I know. And I’ve talked with Ismail, too.”

Suddenly, some fight surges into Abu Raja.

“No. Ismail is a confused boy. I only met him one time. He has had very little to do with my operation.”

He’s protecting Ismail again. Amid the wreckage his life’s become, he is trying to do the honorable thing.

“I understand. You know though, there is one thing that still troubles me.”

He sits quietly and waits for me to continue. I pause. He continues to wait. I can see him scrape together some defensive energy.

“The thing is, I don’t get why Abu Haydar went to the farmhouse with you, Abu Gamal, and Abu Bayda.”

“What is your question?” he says that so quietly that I barely pick it up.

“Well, Abu Haydar was released four months ago from Abu Ghraib. Why would he risk going to the house with you after such a narrow escape?”

“I don’t know,” comes his rote reply.

“Why would he risk capture again?” I am genuinely puzzled by this. It doesn’t make sense to me.

“Maybe Abu Shafiq told him.”

I freeze.

Abu Shafiq is Abu Raja’s boss. Why would Abu Shafiq be talking to Abu Haydar if he were just a cameraman?

I try to keep my face a mask, but I think the shock registers. He’s looks at me worriedly, realizing he just gave up something very valuable.

I have to pounce on this quickly.

“When did Abu Shafiq tell him?”

“I’m not sure,” Abu Raja hesitates.

“But Abu Haydar and Abu Shafiq met together?”

Desperate, his eyes search the room.

“Abu Raja, are you telling me that Abu Haydar and Abu Shafiq met together?”

“Yes. They met one time.”

“Why?” I fire each question at him as soon as he finishes each answer, giving him no chance to think.

“I don’t know why they met.” It is more lament than answer.

“But they met. Without you?”

He doesn’t want to answer that one.

“Abu Raja, they met without you?”

“I’m just…I don’t know. I’ve tried to tell you so many things I’ve forgotten what I’ve told you.”

“They met without you?”

“Yes. That I know of.” He sounds like he’s just made a confession.

“How do you know they met?”

“I saw them on the street together, talking.”

“One time?”

“Yes one time.”

“Let me ask you this. What can I do for you?”

He sighs with relief.

“Thank you. Thank you so much.”

“We’re here to help.”

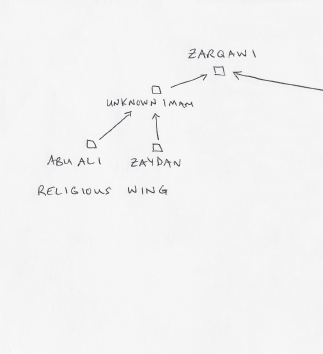

Ten minutes later, I’m back in the ’gator pit, my mind spinning. We’ve gotten this all wrong from the very beginning, and I need to think it through. I sit down at my desk and pull out the wire diagram that I’ve made based on what we thought we knew about the Group of Five.

Abu Gamal is the bomb maker. He was at the house to wire the suicide vests before their mission. Abu Raja is Al Qaida’s media czar. He says he’s the leader of the group. Abu Bayda, the oldest, turns out to be Al Qaida’s northern regional commander. Abu Haydar is just the cameraman.

Baloney.

Maybe we have this all wrong. First, why would Abu Bayda be there? If this was just another preface to a series of suicide bombings, why would such senior men be present? Maybe the target was significant. Maybe this was supposed to be on the scale of the Golden Dome or larger.

That might make some sense. But that still doesn’t explain why a regional commander is in a house hundreds of miles from his area of operation. Why would he care about an operation destined to hit Baghdad?

And it doesn’t explain what Abu Raja just gave me. Abu Haydar is no cameraman. He met alone with Abu Raja’s

boss, Abu Shafiq. That strongly suggests those two are either equals, or even that Abu Haydar is Abu Shafiq’s boss.

Abu Raja isn’t the leader of the Group of Five. Abu Haydar is.

And if he’s higher in the chain of command than Abu Raja, that puts him right inside Zarqawi’s inner circle.

Why risk bringing so many senior leaders to one suicide bombing preshow? What if they weren’t at the farmhouse for a suicide strike?

Holy shit. Maybe we really do have this all backwards. Maybe the suicide bombers were there to protect the Group of Five. They were having a meeting, perhaps to discuss Iraqwide strategy, which would explain Abu Bayda’s presence. If it was just a regional planning session, there’d be no reason to have Abu Bayda there. I wish we’d been able to interrogate the fifth member of the group. He might have given us something useful. As far as I know, though, he’s still in the prison hospital at Abu Ghraib.

If this was a national Al Qaida conference, there would need to be a leader with higher prestige than the senior propaganda officer and a regional commander. That suggests two things: if Abu Haydar’s actually higher than Abu Shafiq, then he was there to represent Zarqawi. If not, either Zarqawi’s operations officer, Abu Ayyub al Masri, or Zarqawi would have been expected at the meeting. Maybe both.

Abu Haydar is the key.

DICE ROLL

G

ENERAL

A

LLENBY

:

You acted without orders, you know.

T. E

.

L

AWRENCE

:

Shouldn’t officers use their initiative at all times?

G

ENERAL

A

LLENBY

:

Not really. It’s awfully dangerous.

—Lawrence of Arabia,

1962

A SINGLE, EMPTY HAND

1100

MEETING, MAY

1, 2006

T

HE GROUP OF

Five seems to be the compound’s only link to Zarqawi. But Abu Bayda isn’t talking about those above him, nor is Abu Raja. Abu Haydar isn’t talking at all.

Randy’s standing in front of all of us. He’s put one foot up on a chair again, his signature meeting pose. He’s frustrated and angry and filled with a sense of urgency. Not only is the pressure—from the president down to the task force commander—greater than ever, but Randy’s a short timer now. He’s due to leave us in a matter of weeks and he wants Zarqawi badly. He doesn’t want to head home after all this time without accomplishing the mission.

He runs through all our current detainees. We have a new crop. Naji and Jamal are gone. We found an uncle who has taken them in. I can only hope that he’ll try to undo the damage the father inflicted on young Naji’s mind. That’s a thin reed to grasp, though. Chances are that as soon as he can

wield a knife, we’ll catch him on one of Al Qaida’s beheading videos.

“I know I’ve said this a million times, but we’ve got to pick up the pace,” Randy vents. “We’ve got to close the gap. Enough said.”

He sits down at the head table and calls for the first slide. Abu Haydar’s face appears on the screen in front of us.

At the 2300 meeting last night, Mary had again recommended his transfer. She still hasn’t gotten anything out of him.

Lenny stands. He looks agitated.

“Nothing to report. Detainee still maintains that he was only a cameraman.”

Randy grinds his teeth. “Recommendation?”

“Transfer to Abu Ghraib.”

“Please,” I hear Mary whisper from a chair behind me, pleading.

Randy squints at Lenny. He looks pained and pissed off. He exhales hard and finally says, “Approved. Get him out of here.”

The meeting breaks up. The last time I asked Randy if we could put somebody else on Abu Haydar, he made it clear that would never happen. As I left his office, he told me not to bring it up again. The look in his eye told me I was dangerously close to stepping over the line.

Abu Bayda is still considered the leader of the Group of Five. Abu Haydar is still officially the cameraman. Yet everything in me screams that he’s the link. He’s the guy we need to get talking.

And it won’t happen. Mary and Lenny have tried to control him, but he has maintained control the entire time. He’s

played them both and in every interrogation I’ve watched, it is clear he has no respect for them. In return, they treat him with contempt.

As I leave the conference room, I approach Randy. He eyes me warily, as if he expects me to barrage him with more requests. Instead, I ask, “What time are the prisoners being transferred today?”

“The admin guy says twenty-three hundred hours.”

Twelve hours from now. I return to my desk and study my computer monitor.

We’re going to lose everything we’ve worked for with the Group of Five and a shot at Zarqawi. I know it. I can feel it. But, will Abu Haydar ever talk? Our new methods have had success with Abu Ali, Zaydan, Ismail, Abu Gamal, Abu Raja, Abu Bayda, and other small fish. But even they have their limits. Nobody spills all. Except for Naji, that is. Our new methods have rolled up many networks, but Abu Raja, Abu Bayda, and Abu Gamal never gave up their boss.

Maybe our new methods won’t work on Abu Haydar either. The trouble is, we haven’t been able to try them.

What am I going to do?

Nothing. Nothing can be done. I start editing the day’s reports.

I look at the clock. Thirteen hundred already. Abu Haydar gets transferred in ten hours.

I grab a notebook and head over to the Hollywood room. Steve, who just got back to us from his other mission, is in the middle of an interrogation with Abu Raja. Trying to distract myself, I tune in.

It’s going nowhere. Steve tries to get him to give up Abu Shafiq, but Abu Raja’s not budging. At one point he says,

“I’ve told you everything I know already. I just want to leave. I don’t care about the consequences. I just can’t take these endless questions anymore.”

I close my eyes and rub my temples.

How many times have we captured so many senior leaders in one place?

Surely, there will be other leads, and other branches to follow. Maybe we can find another way to Abu Shafiq.

I switch to another screen and press a few buttons to listen in. Rachel, a new ’gator, a blonde-haired, twice-divorced mother of three, is going over a map with a former Fedayeen, one of Saddam’s personal bodyguards. She’s using an approach I taught her that leverages hope. She’s mixing new and old methods. In return, the former Fedayeen is providing targets. Maybe there’s hope here. I keep watching.

Yet this will take days, maybe weeks, to develop. And in the meantime, how many innocent Iraqis will die? How many American soldiers will be ambushed and killed? How many suicide bombers will turn marketplaces into bloody bedlam?

Abu Haydar is the key to stopping the carnage.

The rules of this game are rigged. Somebody above Randy, above Roger, is micromanaging our unit and deepening the division between the old-school and new-school adherents.

Maybe Abu Raja didn’t slip. Maybe he handed me that piece of intel as an approach. He’s already proven he can be deceptive. Maybe Abu Haydar is just a cameraman.

No. If he were just a cameraman, he never would have taken the risk of going to the farmhouse—not with one stay at Abu Ghraib in his past. He’s committed. He’s cunning

and highly intelligent. He has all the hallmark behaviors of a leader.

He’s the one. I know it. I go back to editing reports.

I look at my watch. Fifteen thirty. An hour and a half has passed. We lose Abu Haydar in eight hours, thirty minutes.

I run to the chow hall to grab food for my new ’gator, who won’t have time to make it before the evening meal finishes. I bring the food back and leave it on her desk. I walk back to the Hollywood room to check on the interrogations. Steve comes in and asks for permission to give a detainee an extra blanket. I approve. He says the guy is a nobody, but he’s helped a little bit. Maybe that will turn up something. I return to the ’gator pit.

I sit down at my desk and start correcting more reports. The little clock in the corner of my screen reads 1630. I can’t stop looking at it.

We’re six hours and thirty minutes away from letting our biggest fish slip from our grasp. I read another report.

Across from me, Randy is feverishly sorting through piles of paper on his desk. Occasionally, he utters a curse under his breath. I check the time. Fifteen minutes before 1700. He’s scrambling to get his notes together for his daily briefing of the task force’s senior leadership.

Inspiration strikes. Perhaps I can use his distraction to my advantage.

No. I’ve got to play by the rules others have put in place. They’re there for a reason, and my role is not to judge them. My role is to uphold them. To respect them.

How many lives will be on your hands if you don’t at least try? The window will close in five minutes.

My heart starts to race. I am a major in the United States

Air Force. I take orders. I give orders. I follow the rules. I perform my duty.

I swore an oath to the Constitution to protect this country from all enemies.

Where do we draw the line? If everyone decided they knew what was best for the country, best for their unit and command, no matter what the rules may be, we’d have total chaos. The system would break down.

But this is wrong. We’ve had the wrong ’gators on the right man for three weeks without any result. Our hands are tied. We cannot try anything new. We can’t run another approach. And Zarqawi will slip through our grasp once again. We’ll be back to where we were in 2004.

Randy puts a few final pages on top of one pile and scoops them under his arm, looking frazzled.

It’s now or never. If I’m wrong, my career ends. I’ll be thrown out of Iraq, sent home in disgrace. But if I’m right, lives will be saved.

If I don’t do this, will I look back in twenty years and see every suicide attack from now until Zarqawi is stopped as my burden?

An image flickers into my mind from a video Ismail admitted editing. No doubt Abu Raja distributed it far and wide as an example of Al Qaida’s daring resistance.

It starts with a typical Baghdad street scene. Men in dishdashas move along, conducting business and buying goods. Women in black burkas hustle past the cameraman. He walks forward through the crowd, and it becomes clear he’s following another man dressed in a white dishdasha and a tan linen vest.

They walk past an outdoor restaurant. People sit clustered

around tables, laughing and drinking tea. Parents shepherd children along. One little girl holds her father’s hand as he crosses the street from camera left to camera right.

The man in the linen vest continues on. We never see his face, just the back of his head. For a moment, the cameraman loses him in the crowd, but then he spots him again as he emerges near a busy intersection. The camera halts. It zooms in on Linen Vest, who steps between cars stuck in a traffic jam.

The explosion is so intense that the camera swings towards the ground. All we see is pavement, but we hear the sounds of mass panic clearly: screams of agony, pleas for help, sobbing women. In the distance, alarms wail.

The cameraman seems to regain his footing. The scene pans slowly upward. The street is desolate. Bodies lay in heaps. Smoke coils over burnt and blackened cars parked by the curb. A huge charred crater mars the middle of the intersection. A truck burns nearby.

The little girl, at most ten years old, lies in the middle of the street at camera right. Her body is sprawled next to her dead father’s. Her hand is stuck straight up in the air, as if her dying act was to reach out for the comfort of her father’s grip, only to find empty air.

Our enemy holds this up to the world as proof of their resolve against us.

I will not hate the enemy, but I will do everything I can to stop it.

I stand up. Randy is heading out the door. I give chase.

As I cross paths with Randy in the hallway, I can see that he’s agitated and consumed by his thoughts. I mumble as I pass, “Mind if I give Abu Haydar a shot?”

He doesn’t look at me. He can’t hear me. I’m an aggravation he doesn’t have time for right now.

“Whatever,” he says.

He strides ahead down the hallway, leaving me in his wake.

I take that as approval and head for the cellblock.