How They Started (16 page)

Authors: David Lester

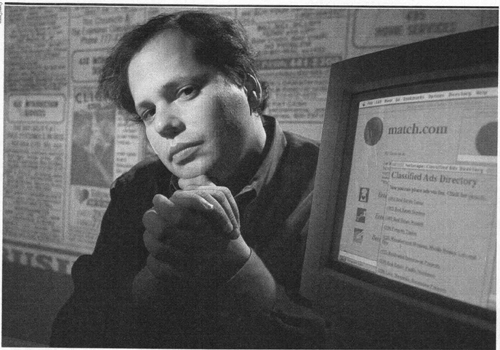

An early version of Match.com.

Early on, ECI made a bold decision: to focus the marketing entirely on women who were already online.

Later on, the company widened its reach and began a multifaceted campaign through traditional print and television media, targeting the 25 million Americans who already used dating services but did not have a compelling enough reason to go online.

It was not long before the company’s continued growth attracted the attention of more outside investors, and in 1994 Electric Classifieds received its second round of funding from venture capitalists, raising $1.7 million led by Silicon Valley venture capital firm Canaan Partners.

“It was pretty easy to raise funding because it was pretty novel—there was some skepticism at first, but once we became the market for new relationships, that disappeared.” Gary says.

In 1995, just after the first round of venture capital, the early pace of expansion forced Gary to buy one of the largest servers offered by Sun Microsystems, costing $300,000. The problem was, the venture capital money had already been tied up in other parts of the expansion, leaving the company with no money to pay for the server.

“I told the sales guy that it was great, the machine looked good, but we had one problem—I had no money to pay for it!” he says. “He told me I was going to put him out of business—so I gave him my new venture guy’s home phone number and told him to call him up and get the money from him. I made it his problem!” Needless to say, Gary recalls that particular venture capitalist being less than impressed. Despite these early hurdles, the Match.com website finally went live in April 1995, marking the birth of the site as we know it today.

Gary shows how Match.com sorts ads according to the user’s location and preferences.

The combination of Electric Classified’s innovative business plan and its huge growth soon proved irresistible to the mass media and Match.com was catapulted out of obscurity to become the darling of the business world. It was the subject of articles in

Wired

and

Forbes

, with Gary being named #36 on a list of the 100 most influential people on the Internet. His quirky persona as CEO also proved appealing, with a notable example being an early television interview in 1995 in which he proclaimed that Match.com would “bring more love to the planet than anything since Jesus Christ.”

Electric Classifieds also saw Match.com’s appeal spread to some unexpected sectors. The site quickly proved popular among older women, for example. Gary had thought that this group would be the most resistant to an online dating service, but their troubles finding men in real life led them to embrace the connectivity and global appeal that Match.com offered.

Despite this success, troubles were beginning to grow between Gary and his investors. The board had doubts about Gary’s ability as CEO, aggravated by what he admits was his early immaturity. A major flashpoint developed when investors found out that Match.com was beginning to target the gay and lesbian sector. Gary saw this group as a loyal market that deserved to be served—but certain investors perceived it differently. “They went ballistic,” says Gary. “We had some towering arguments about it.”

Another fundamental disagreement soon arose between Gary and the board over the wider direction that ECI was to take. The board was increasingly at odds with Gary over strategy: they wanted to use ECI as a vehicle to sell classifieds technology to newspapers, a process that Gary fundamentally disagreed with.

“[Newspapers] were slow moving and I could see how long it took them to do anything at all. Even though some of them were a hundred thousand times bigger than us, I always knew we could take them on ourselves. I always knew working with the newspapers would turn out to be a dumb idea.”

These incidents and disagreements over strategy led to Gary leaving his post as Match.com CEO in mid-1995. “We had a big fight. I left,” says Gary, simply. “It was a great time to be starting other things, so I moved on to new ventures.”

“It’s the exception rather than the rule that the founder is a good CEO,” Gary says. “The guy that has the idea is not normally the guy with the skills to manage 300 people.”

Gary remained on the ECI board as the chairman, helping with the overall strategy and vision until the Match.com business was sold off to Connecticut firm Cendant in 1998 for $7 million. Again, it was a decision that Gary strongly resisted, believing the brand to be vastly undervalued. From the investors’ point of view at the time, it was a canny piece of business, selling a brand for over three times what they bought it for just a few years after investing. But Gary’s estimation of the true worth of the business proved to be much closer to the mark, as Cendant sold the site on to US giant Ticketmaster for the eye-watering sum of $50 million just one year later. Gary resigned from the ECI board after the sale to Cendant, pocketing just $50,000—as well as a lifetime account on Match.com.

Despite the acrimonious split, Gary believes his experience at Match.com was an instructive one. He learned that despite having a knack for good ideas and keen business insight, he was not born to be a CEO—a lesson he says can serve as a cautionary tale for other would-be entrepreneurs.

“It’s the exception rather than the rule that the founder is a good CEO,” Gary says. “These cases of Amazon, with Jeff Bezos being the founder and CEO, or Mark Zuckerberg—these aren’t normal. The guy that has the idea is not normally the guy with the skills to manage 300 people.”

Gary also learned to take a more inclusive approach with investors rather than the combative style he adopted while at the company. He advises: “When the process begins of building and getting a CEO in, you may as well be part of the process as opposed to fighting it.” He adds that you have to “kiss lots of frogs” to get the “right” investors and only regrets his choice in hindsight, if not the investment itself.

Electric Classified’s sale of the Match.com brand proved to be the beginning of the end for the business. Changing its name to Instant Objects, the company persisted with the doomed goal of selling backend technology to newspapers, and, despite raising an additional $25 million in venture capital, finally shut its doors in 2001.

However, this wasn’t quite the end of the ECI saga. In 2004, the defunct company’s outstanding debt was bought by none other than Gary himself, who then sold off some patents he had filed while at the company for a handsome profit. “I bought the debts for maybe $300,000 and made a couple of million dollars from the sale,” he says. “It’s a nice story.”

Where are they now?

Today, Match.com competes with PlentyOfFish.com as the world’s leading dating site and established the template for many other imitations, fulfilling the potential that Gary always knew it had.

It claims to have over 20 million members (1.3 million of whom are paying subscribers) with a 49:51 male:female ratio. It’s also a truly global affair, with sites in 25 different countries in eight languages. The company is still under the control of IAC (InterActive Corp.) and would comfortably be valued in a multiple of hundreds of millions of dollars.

“I’m happy it’s done so well,” Gary says. “I knew as soon as I had the idea it was going to be huge—I’ve got my vision wrong many times but I got this one right.”

And Gary’s life after Match.com has proved just as eventful. After leaving the company, he started NetAngels, a venture that offered early collaborative filtering technology that was merged with another company, Firefly, and was eventually sold to Microsoft.

In the late 1990s, Gary became embroiled in one of the longest running and most notorious disputes in Internet history when fraudster Stephen Cohen stole the Sex.com domain—which Gary had registered for free when starting Electric Classifieds—and used it to form the basis of a multi-million-dollar pornography empire. This battle to save what was rightfully his would take Gary many painful years, with Cohen’s evasiveness almost leading to his ruin. Eventually, Gary obtained some of what was owed to him, receiving a $65 million judgment that included Cohen’s mansion in the prestigious San Diego neighborhood of Rancho Santa Fe. Gary now lives in the mansion, and Cohen bought himself a lengthy prison sentence.

Today, Gary devotes his time to investing in ethical and sustainable businesses and estimates he is an investor in 15 such ventures. A notable recent investment success has been Clean Power Finance, founded in 2007 as an online service that enables solar buyers and sellers to connect with financial products. Kleiner Perkins and Google were some of the other investors, and the company reportedly channels $1 million into the solar industry every day.

But did Gary ever achieve his original goal of finding love? “I finally got married about four years ago—but it wasn’t through Match.com!”

Gary explains. “It was a hybrid model—I offered a reward on the Internet of a trip to Hawaii for two if you set me up with my future wife. This guy I know set me up with my wife, and he got his holiday, so everyone was happy.”

How 140 characters changed the world

Founders:

Jack Dorsey, Christopher Isaac “Biz” Stone and Evan Williams

Age of founders:

29, 31, 33

Background:

Software developers/Google employees/serial entrepreneurs

Founded in:

2006

Headquarters:

San Francisco, California

Business type:

Social media/microblogging

In five short years, Twitter grew—and

grew

—

into a tool that revolutionized global communications. It became so ubiquitous that using it became a verb: to tweet. The brief status updates of Twitter would change the way news is reported, governments are toppled, and charitable donations are solicited.

But Twitter is almost as famous for what it hasn’t done: turn a profit. Despite attracting a huge audience and raising over $1 billion in venture capital, Twitter continues to struggle to find a business model that will let it cash in on its popularity.

As a teenager growing up in St. Louis, Missouri, Jack Dorsey

created software that helped taxi and ambulance dispatchers locate their vehicles. Jack attended Missouri University of Science and Technology, then transferred to New York University before dropping out in 1999.

He moved west, taking up residence inside the former Sunshine Biscuit Factory in Oakland, California, and he began working on a Web-based dispatch start-up idea. In July 2000, inspired by the Web-posting service LiveJournal, he got an idea for a simple, real-time update service—a more “live” LiveJournal.

He sketched the idea on a sheet of wide-ruled notebook paper. There would be a small box for writing what you were doing, room for a bit of contact information, and a search bar for finding others on the service.

That was it. Jack wanted to call it Stat.us.

Evan Williams grew up on a farm in Clarks, Nebraska. He lasted a year and a half at the University of Nebraska before dropping out in favor of a string of tech jobs. In 1996 he moved to Sebastopol, California, to work for technology publisher Tim O’Reilly and his O’Reilly Media. He began in marketing but floundered as a staffer and switched to writing code as an independent contractor. “I was bad at working for people,” Evan would later say.

In 1999 he co-founded Pyra Labs with ex-girlfriend Meg Hourihan. Pyra’s hit product was a simple, early Web-logging platform called Blogger, a term Evan coined.

Blogger lacked a business model—the platform was free. Evan wanted to focus on improving the user experience and building the audience first, then figure out how to make money.