How the Whale Became (5 page)

Read How the Whale Became Online

Authors: Ted Hughes

There was one creature that never seemed to change at all. This didn’t worry him, though. He hated the thought of becoming any single creature. Oh no, he wanted to become all creatures together, all at once. He used to practise them all in turn – first a lion, then an eagle, then a bull, then a cockatoo, and so on – five minutes each.

He was a strange-looking beast in those days. A kind of no-shape-in-particular. He had legs, sure enough, and eyes and ears and all the rest. But there was something vague about him. He really did look as if he might suddenly turn into anything.

He was called Donkey, which in the language of that time meant ‘unable to stick to one thing’.

‘You’ll never become anything,’ the other creatures said, ‘until you stick to one thing and that thing alone.’

‘Become a lion with us,’ the Lion-Becomers said. ‘You’re so good at lioning it’s a pity to waste your time eagling.’

And the eagles said: ‘Never mind lioning. You

should concentrate on becoming an eagle. You have a gift for it.’

All the different creatures spoke to him in this way, which made him very proud. So proud, in fact, that he became boastful.

‘I’m going to be an Everykind,’ Donkey cried,

kicking

up his heels. ‘I’m going to be a

Lionocerangoutangadinf

.’

Half the day he spent on a high exposed part of the plain practising at his creatures where everyone could see him. The other half he spent sleeping in the long grass. ‘I’m growing so fast,’ he used to say, ‘I need all the sleep I can get.’

But Donkey had a secret worry. He had no means of earning his living. He couldn’t earn his living as a lion – not when he only practised at lion five minutes a day. He couldn’t earn his living as any other creature either – for the same reason.

So he had to beg.

‘When you see me grow up into a

Lionocerangoutangadinf,

’ he said, as he begged a mouthful of fish from Otter, ‘you’ll be glad you helped me when I was only learning.’

And he went off kicking up his heels.

Before long the animals grew tired of his begging. It took them all day to find food enough for

themselves

. So whenever Donkey came up to them to beg they began to tease him:

‘What?’ they cried. ‘Aren’t you the finest, greatest creature in the world yet? What have you been doing with your time?’

This made Donkey furious. He galloped off to a high hill, and there he sat, brooding.

‘The trouble is,’ he said, ‘there’s no place among these creatures for somebody with real ambition. But one day – I’ll make them stare! I’ll be a better lion than lion, a better eagle than eagle, and a better kangaroo than kangaroo – and all at the same time. Then they’ll be sorry.’

All the same, he wished he could earn his living without having to beg.

As he sat, he heard a long sigh. He looked around. He hadn’t noticed that he was so near Man’s farm. He looked over the fence and saw Man sitting beside a well, with his head resting in his hands. As he looked, Man gave another sigh.

‘What’s the matter?’ asked Donkey.

Man looked up.

‘I’m weary,’ he said. ‘Drawing water from this well is hard work.’

‘Hard?’ Donkey cried. ‘If it’s strength you’re

wanting

, here I am. I’m the strongest creature on these plains.’

‘But still not strong enough to draw water,’ sighed Man.

‘Just watch this.’ Donkey marched across, took hold of the long pole that stuck out over the well, and began to drag it round. He had often seen Man doing this, so he knew how. Water gushed out of a pipe on to Man’s field of corn.

‘Wonderful!’ cried Man. ‘Wonderful!’

Donkey flattened back his ears and pulled all the harder. Man danced around him, crying:

‘You’re a marvel. Oh, what I wouldn’t give to have you working for me.’

As he said that, Donkey got an idea. He stopped.

‘If you’ll give me food,’ he said, ‘I’ll do this every day for you.’

‘It’s a bargain!’ said Man.

So Donkey started to work for Man.

Only a little bit each morning, mind you. He still spent most of the day out on the plains practising at all his creatures. Then he retired early to sleep in the little shed that Man had made for him – it was dark, out of the wind, and the floor was covered with deep straw. Lovely! There he would lie till it was time for work next morning.

One day Man said to him:

‘If you’ll work twice as long for me, I’ll give you twice as much food.’

Donkey thought:

‘Twice as much food means twice as much strength. And if I’m going to be a

Lionocerangoutangadinf

– well – I shall need all the strength that’s going.’

So he agreed to work twice as long.

Next day, Man asked him the same again. Donkey agreed. And the next day, and again Donkey agreed. He was now working from dawn to dusk. But the pile of food that Man gave him at the day’s end! Well, after eating it, Donkey could do nothing but lie down on his straw and snore.

After about a week of this he suddenly thought:

‘Here I am, being gloriously fed. Getting stronger and stronger. But I never have time to practise at my

creatures. How can I hope to become a

Lionocerangoutangadinf

if I never practise my creatures?’

So what did he do? He couldn’t very well practise while he was working. The sight and sound of it would have terrified Man, and Donkey didn’t want to lose his job. So he did the only thing he could. He began to practise in his head.

Soon he got to be wonderfully good at this. He could fancy himself any creature he wished – a mountain goat, for instance, leaping among the clouds from crag to crag, or a salmon, climbing a swift fierce torrent – for hours at a time, all in his head. He would quite forget that he was only

walking

round a well.

Once or twice Man removed him from the well and set him to draw a plough. But donkey was so absorbed in practising at his creatures inside his head that he forgot to turn at the end of the furrow. He went ploughing straight on, through the hedge and into the next field. After this, Man never asked him to do anything but walk around the well, and Donkey was quite contented.

So it went on for several years, and Donkey fancied that he was becoming more and more skilful at his creatures. ‘I mustn’t be in too great a hurry,’ he said to himself. ‘I want to be better at everything than every other creature – so a little bit more practice won’t hurt.

So he went on. Always staying on with Man for just a little bit more practice inside his head.

‘Soon,’ he kept saying, ‘soon I shall be perfect.’

At last it seemed to Donkey he was nearly perfect.

‘A few more days, just a few more days!’ Then he would burst out on to the plains, the first

Lionocerangoutangadinf

. Within three days, perhaps even within two, the animals would crown him their king – he was sure of that. Just as he was thinking these lovely thoughts he heard a sudden cry. He looked up and saw Man running towards his house, his arms in the air.

At the same moment, over the high fence, came Lion.

Donkey stood, and watched Lion out of the corner of his eye. He tilted one fore-foot carelessly.

Lion stared at him.

At last, making his voice sound as friendly as he could, Donkey said: ‘My word, Lion-Becomer, you’ve changed. Are you Lion yet?’

Lion turned away from him without a word and walked up the path. When he reached Man’s house, he stood up on his hind legs and, lifting one paw, like a lion in a coat of arms, began to beat upon the door.

‘Throw out your wife and children, Man!’ he roared.

Man was crouching under the table inside the house, trembling all over, not daring to breathe.

Finally Lion got tired of beating the door, which was of thick wood and studded with big bolts. He turned round and began to sniff among the

outhouses

and gardens. He came to Donkey again, who was still propped idly on one foreleg beside the well.

‘Hello again. Lion,’ said Donkey, and he let his voice be ever such a little bit scornful. ‘Your hunting

isn’t so good, is it? I think I could give you a lesson or two in lioning,’

Lion stared, amazed.

‘Now,’ thought Donkey, ‘now to reveal my true self. Now to reveal what I have made myself after all these years of hard practice.’

And he gave a great leap and roared.

‘See!’ he cried. ‘This is the way!’

And again he leapt and roared, leapt and roared. He became so taken up with his lioning that he

completely

forgot about Lion.

Now it was years since Donkey had actually tried to leap or roar. He was far too stiff with his years of hard work to leap, and his voice had become stiff as his muscles.

So, though it seemed to him he was doing a

wonderful

lion, he was really only kicking out his heels stiffly, and sending up a harsh bray.

But he was delighted with himself. He went on, leaping and roaring, as he thought, leaping and

roaring

, so that his harness clattered, the long pole bounced and banged, and Lion screwed up his eyes in the dust from the kicking-out feet.

At last Lion could stand it no longer. He raised his paw, and with one blow knocked donkey clean into the well. He then jumped back over the fence and returned to his wife, who was waiting on the skyline.

Poor Donkey! When Man hauled him out of the well he was in a sorry state. But he was a wiser Donkey. That night he ate his oats and lay down with a new feeling. No more Lionocerangoutangadinf for him. no more pretending to be every creature.

‘It’s best to face the truth,’ he said to himself, ‘and the truth is I’m neither a lion nor an eagle. I am a well-fed, comfortable, hard-working Donkey.’

He could hear the lions roaring hungrily out on the plains, and he thought of the antelopes running hither and thither looking for a safe corner and a place out of the wind. He pushed his head under the warm straw, and smiled into the darkness, and fell into a deep sleep.

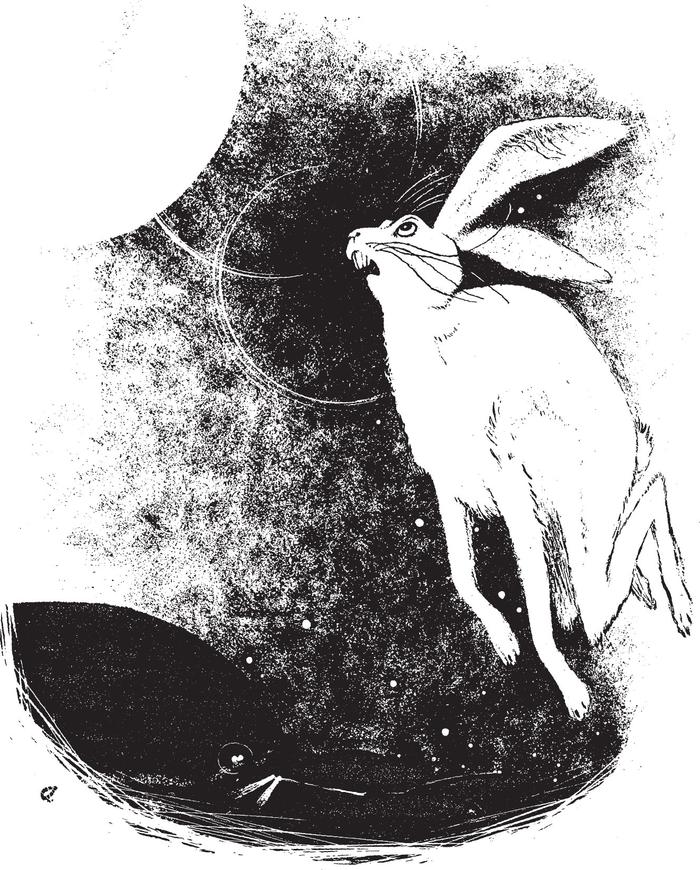

Now Hare was a real dandy. He was about the

vainest

creature on the whole earth.

Every morning he spent one hour smartening his fur, another hour smoothing his whiskers, and another cleaning his paws. Then the rest of the day he strutted up and down, admiring his shadow, and saying:

‘How handsome I am! How amazingly handsome! Surely some great princess will want to marry me soon.’

The other creatures grew so tired of his vain ways that they decided to teach him a lesson. Now they knew that he would believe any story so long as it made him think he was handsome. So this is what they did:

*

One morning Gazelle went up to Hare and said:

‘Good morning, Hare. How handsome you look. No wonder we’ve been hearing such stories about you.’

‘Stories?’ asked Hare. ‘What stories?’

‘Haven’t you heard the news?’ cried Gazelle. ‘It’s about you.’

‘News? News? What news?’ cried Hare, jumping up and down in excitement.

‘Why, the moon wants to marry you,’ said Gazelle. ‘The beautiful moon, the queen of the night sky. She wants to marry you because she says you’re the handsomest creature in the whole world. Oh yes. You should just have heard a few of the things she was saying about you last night.’

‘Such as?’ cried Hare. ‘Such as?’ He could hardly’ wait to hear what fine things moon had said about him.

‘Never mind now,’ said Gazelle. ‘But she’ll be walking up that hill tonight, and if you want to marry her you’re to be there to meet her. Lucky man!’

Gazelle pointed to a hill on the Eastern skyline. It was not yet midday, but Hare was up on top of that hill in one flash, looking down eagerly on the other side. There was no sign of a palace anywhere where the moon might live. He could see nothing but plains rolling up to the farther skyline. He sat down to wait, getting up every few minutes to take another look round. He certainly was excited.

At last the sky grew dark and a few stars lit up. Hare began to strut about so that the moon should see what a fine figure of a creature was waiting for her. He looked first down one side of the hill, then down the other. But she was still nowhere in sight.

Suddenly he saw her – but not coming up his hill. No. There was a black hill on the skyline, much

farther to the East, and she was just peeping silver over the top of that.

‘Ah!’ cried Hare. ‘I’ve been waiting on the wrong hill. I’ll miss her if I don’t hurry.’

He set off towards her at a run. How he ran. Down into the dark valley, and up the hill to the top. But what a surprise he got there! The moon had gone. Ahead of him, across another valley, was another skyline, another black hill – and that was the hill the moon was climbing.

‘Wait for me! Wait!’ Hare cried, and set off again down into the valley.

When he got to the top of that hill he groaned. And no wonder. Far ahead of him was another dark skyline, and another hill – and on top of that hill was the moon standing tiptoe, ready to fly off up the sky.

Without a pause he set off again. His paws were like wings. He ran on the tops of the grass, he ran so fast.

By the time he got to the top of this hill, he saw he was too late. The moon was well up into the sky above him.

‘I’ve missed her!’ he cried. ‘I’m too late! Oh, what will she think of me!’

And he began leaping up towards her, calling:

‘Moon! Moon! I’m here! I’ve come to marry you.’

But she sailed on up the black sky, round and bright, much too far away to hear. Hare jumped a somersault in pure vexation. Then he began to listen – he stretched up his ears. Perhaps she was saying terrible things about him – or perhaps, yes, perhaps flattering things. Perhaps she wanted to marry him

much too much ever to think badly of him. After all, he was so handsome.

All that night he gazed up at the moon and listened. Every minute she seemed more and more beautiful. He dreamed how it would be, living in her palace. He would become a king, of course, if she were a queen.

All at once he noticed that she was beginning to come down the other side of the sky, towards a black hill in the West.

‘This time I’ll be waiting for her,’ he cried, and set off.

But it was just the same. When he got to the top of the hill she was no longer there, but on the farther hill. And when he got to the top of that, she was on the next. And when he got to that, she had gone down behind the farthest hills.

Hare was furious with himself.

‘It’s my own fault,’ he cried. ‘It’s because I’m so slow. I must be there on time, then I shan’t have to run after her. To miss the chance of marrying the moon, and becoming a king, all out of pure slowness!’

That day he told the animals that he was courting the moon, but that the marriage day was not fixed yet. He strutted in front of them, and stroked his fur – after all, he was the creature who was going to marry the moon.

He was so busy being vain, he never noticed how the other creatures smiled as they turned away. Hare had fallen for their trick completely

That night Hare was out early, but it was just the

same. Again he found himself waiting on the wrong hill. The moon came over the black crest of a hill on the skyline far to the East of him. Hill by hill, he chased her into the East over four hills, but at last she was alone in the sky above him. Then, no matter how he leapt and called after her, she went sailing on up the sky. So he sat and listened and listened to hear what she was saying about him. He could hear nothing.

‘Her voice is so soft,’ Hare told himself.

He set off in good time for the hill in the West where she had gone down the night before, but again he seemed to have misjudged it. She came down on the hilly skyline that was further again to the West of him, and again he was too late.

Oh, how he longed to marry the moon. Night after night he waited for her, but never once could he hit on the right hill.

Poor Hare! He didn’t know that when the moon seemed to be rising from the nearest hill in the East or falling on to the nearest hill in the West, she was really rising and falling over the far, far edge of the world, beyond all hills. Such a trick the creatures had played on him, saying the moon wanted to marry him.

But he didn’t give up.

Soon he began to change. With endlessly gazing at the moon he began to get the moonlight in his eyes, giving him a wild, startled look. And with racing from hill to hill he grew to be a wonderful runner. Especially up the hills – he just shot up them. And from leaping to reach her when he was too late,

he came to be a great leaper. And from listening and listening, all through the night, for what the moon was saying high in the sky, he got his long, long ears.