How Soon is Now?: The Madmen and Mavericks who made Independent Music 1975-2005 (46 page)

Read How Soon is Now?: The Madmen and Mavericks who made Independent Music 1975-2005 Online

Authors: Richard King

In the video for ‘Last Train to Transcentral’ a model of the Ford Galaxie drove off the edge of an unfinished motorway flyover and

became airborne. For those closest to them it seemed that an

out-of

-control car flying through the air was as apt a metaphor as any for the duo’s state of mind. Cally Calloman, who had known both members of The KLF, and the members of the inner sanctum had, along with the rest of the industry, looked on at the ascent of The KLF in wonder. At the back of his mind Calloman realised that the size of their success was bound to have repercussions.

‘KLF was so condensed and so crazy. Everyone at Island said, “Oh, Cally, you know Bill Drummond – do you think you can get him to do a remix on the new this single or that single?” Their ascendance from The Timelords on was so steep … it was fantastic, but they were sort of uncontactable apart from Mick, who I like a lot. Mick was the earthbound member of planet KLF. It was a tiny coterie. If you said, “I think Tammy Wynette would be a great voice on this,” you’d get Tammy Wynette, and they went to Clive Davis, to get Tammy Wynette … and he is very much from that school, an old guy who could turn round and say, “Fine, I’ll give you Tammy Wynette” … not “You’re crazy, the demographic is all wrong.” … Bill didn’t even have to explain.’

‘Justified and Ancient’ was a reworking of a track on 1987

(What the Fuck Is Going On)

, another example of how the duo liked to play around with the same themes and ideas or, put another way, were able to rework the same material within the elevated aspect of The KLF. Drummond and Cauty certainly mined their recordings at length for source material – some of the pedal steel on

Chill Out

dates back to Drummond’s solo LP

The Man

.

‘The Stadium House Trilogy records are classic,’ says Houghton, ‘but they had recycled ‘What Time Is Love?’ three times, and got away with it. They weren’t exactly brimming with ideas but it didn’t matter, they just went, “Well, let’s do a rock version, ‘America What Time Is Love?’” and they got away with

it. What Bill and Jimmy had was an incredibly strong sense of commercial potential.

‘America What Time Is Love?’ was the last KLF single and featured former Deep Purple vocalist Glenn Hughes who sang over a frenetic stadium-rock-house version of the track. Seasoned KLF watchers sensed that the song was a carefully constructed, if blatant, attempt to ‘crack America’. ‘A lot of people probably thought that maybe we did have a proper vision,’ says Cauty, ‘but we didn’t really. We were just making it up from day to day. I’m still not sure how any of it would look from the outside.’

The ideas were becoming more and more grandiose. The video for ‘America What Time Is Love?’ featured a longboat being lashed on the high seas and driving rain of Pinewood’s submarine studio as Drummond and Cauty, dressed as knights and playing Gibson Flying Vs urged the boat’s crew and passengers to row harder and faster. The song sampled Motörhead’s ‘Ace of Spades’, and the duo’s work rate was running at an equally frenetic pace that was becoming untenable as thoughts within the camp suggested that The KLF might now have become something of a monster.

‘By the time we got to the end, to “America What Time Is Love?”, it was getting a bit weird really,’ says Cauty. ‘It seemed like it was so easy to have a hit, even though we’d still be putting everything into these records. “America What Time Is Love?” has got so many things in [it]. We had to get two 48-track machines going in the studio, all at the same time, just to get everything we wanted in. It was ridiculous, it was like a Meatloaf record. I think we’d pretty much said everything that was possible to say on a record. It had reached its peak and then really really there was no more.’

The duo began work on a new project,

The Black Room

, a title that was representative of their mental state and their decision,

having sampled Motörhead, to further explore metal and thrash music. They enlisted the help of Ipswich’s Extreme Noise Terror in the studio, starting to lay down tracks of aggressive rhythms and punishing vocals, but the sessions started to stall.

‘The risk just went on being even braver,’ says Calloman. ‘The self-destruct button just went on to be an ogre. They got bigger and bigger and bigger because they could say, “Oh we’ll destroy all this one day,” and one of them would say to the other, “Oh great, destruction that’s fantastic!”’

The KLF signifiers of horned men, capes,

mise en scène

on the grand scale, the Ford Galaxie 500, the duo’s choreographed dance ‘routines’ were all now facets of their lovingly created mythology. While they were always taken seriously by the media, the sense that Drummond and Cauty’s greater role was as pranksters or situationists is a charge that still rankles with them both.

‘Even though there was humour in it,’ says Cauty, ‘we were deadly serious about it, and really meant everything we did. I think that’s one of the reasons why it sort of worked so well, because people can tell when they hear something that these people really mean this. It’s like any kind of art that you do: you have to put everything into it, and if you don’t, then people can tell.’

For Drummond, who has continued to resist any attempts by the media to define whatever his particular preoccupations are at any given time, the idea that The KLF was a project or a scam is one that haunts him still. ‘Every note we played, every single thing that came out, I felt’, he says. ‘We completely meant every moment.’

The KLF’s runaway commercial success meant that they would be duly honoured by the BPI at the 1992 Brit Awards. The band were nominated for Best Artist and Best Single and were invited to perform at the ceremony.

‘Towards the end, because of the scale and success, and the sort of blind acceptance of whatever they did, I think they just felt that what they were doing was meaningless,’ says Houghton. ‘I think they were both pretty close to nervous breakdowns. I think they could have done serious damage to themselves at that point, when they did the Brit Awards. There were bits of that that were totally Ealing Comedy, like when they sent a motorcycle courier up there to pick up their awards. The courier gets there, he picks it up, walks off and then goes back and gets it signed for.’

Drummond and Cauty had planned to mark the Brits with a series of gestures on live television that would be an unforgettable assault on the sensibilities of an audience comprising the great and the good from an industry whose conventions, protocol and standards they had mistrusted and abused since the first JAMs release.

‘I remember meeting them, about six in the morning, that day and they had the dead sheep in the back of the van,’ says Houghton. ‘This is typical of what they would do. They did it all themselves. Bill had driven up that morning to somewhere in Northampton, to pick up this dead sheep, and they really were going to throw blood over the audience and I said, “You can’t do that, you really

cannot

do that,” and I did put that in the

Mirror

or the

Sun

, and it ran that morning: “The KLF are going to throw buckets of blood everywhere” and they were actually stopped from doing that.’

While their plans to cover the music industry in sheep’s blood had been scuppered by Houghton, The KLF still staged a

career-ending

performance to end all career-ending performances. An unhinged-looking Drummond, wide-eyed, on crutches and wearing a kilt, staggered onstage alongside the members of Extreme Noise Terror and Cauty, whose zipped-up clothing made him look like a petrol bomber. Drummond announced

their arrival with the cry of ‘ENT vs The KLF This … is Freedom Television’. As the two bands launched into a hardcore thrash version of ‘3 a.m. Eternal’, the massed black ties of the phonograph industry sat in dumbstruck horror, as ENT treated the Hammersmith Odeon to the sort of set they were used to playing to a wall of stagediving hardcore thrash fans in a rock dive. The spectacle concluded with Drummond chomping on a cigar and firing round after round of blank ammunition from a machine-gun he pointed at all corners of the audience.

One crucial detail had been lost in the chaos of the performance, however. ‘I’ve always had this rock star fantasy, ever since I was young, that I’d have this massive guitar solo,’ says Cauty. ‘I’d been rehearsing it and rehearsing it. This was it. Hammersmith Odeon – I’m gonna do my guitar solo at last, them I’m finished. So of course I come up to the front of the stage and go “wrram” and my lead gets pulled out of my guitar. I’ve only got, like, twenty seconds to do my solo and I spend the whole time just finding the end of the lead to plug it back in and that was it – that was the last thing I ever did in the music business. So tragic, but I’m OK now – but what a lost opportunity that was, ’cause it was a brilliant solo.’

As the band walked off stage, Scott Piering’s voice boomed out over the PA: ‘Ladies and Gentlemen, The KLF have left the music business.’

The performance left the audience feeling aghast and assaulted as, for the first time in its history, a performance by a multimillion selling band at the Brits Award Ceremony was met with silence.

‘It absolutely fucking terrified people,’ says Houghton. ‘Sir George Solti was up for a lifetime achievement award and he was in the front row, and as soon as they started up, he fled the building, hotly pursued by people with clipboards, “You can’t go,

you’ve got an award to accept.” There was just stuff that people didn’t even notice, it was fantastic.’

The KLF had ended their career live on TV in a hail of hardcore metal and machine-gun fire, an act of visceral aggression that was indicative of the fragile mental state of both Drummond and Cauty. ‘We were both exhausted,’ says Cauty. ‘It just happened overnight. Nobody knew it was coming. We just said, “That’s it, we’re deleting all the records, we’re going away, goodbye.”’

With the studio bill and Extreme Noise Terror’s fee still owing (both were later settled), The KLF ceased to exist the moment they walked off stage at the Hammersmith Odeon. Drummond and Cauty, at least in the territories where the decision was theirs to make, deleted the entire KLF back catalogue.

‘I genuinely believe that Bill actually was of a mind to chop his hand off or, who knows,’ says Houghton. ‘They were so crazed at that time that nothing would’ve surprised me. It was kind of spiralling out of control, I think, at that point.’

‘We’d been going so flat out and then we both literally woke up one morning and went, “Well, that’s it, there’s no more,”’ says Cauty. ‘I just remember it was such a relief. It was so exciting, you know. We put this full-page advert in the

NME

and it was great, something new at last.’

Such was The KLF’s popularity and reputation for double bluff that the press second-guessed the duo’s announcement and assumed the band were performing another piece of KLF theatre. The reality was that the non-stop sidestepping and widescreen success of The KLF had tested the limits of both its members. ‘I couldn’t carry on,’ says Drummond. ‘I was about thirty-nine then, and I just had to stop, you know. This had taken over every area of my life. There’s a lot of other things I wanna do. I’m not saying I had a breakdown, in a classical sense, but that’s what it felt like. My marriage came to an end.’

Houghton had been on the journey, if once removed, from its beginnings and had seen their meteoric success and

self-imposed

isolation from the outside world combine to affect their health. ‘They could’ve done something which I think would have to have bordered on self-harm of some sort,’ he says. ‘That’s kind of where it was heading – or something that was actually seriously illegal to the point of getting them into serious trouble.’

The band’s success and legacy and the adventures of the K Foundation that followed are still something Drummond and Cauty are processing today. ‘We never did it for the money,’ says Cauty. ‘Anyway, I wouldn’t recommend it to anybody, as a job, being in The KLF.’

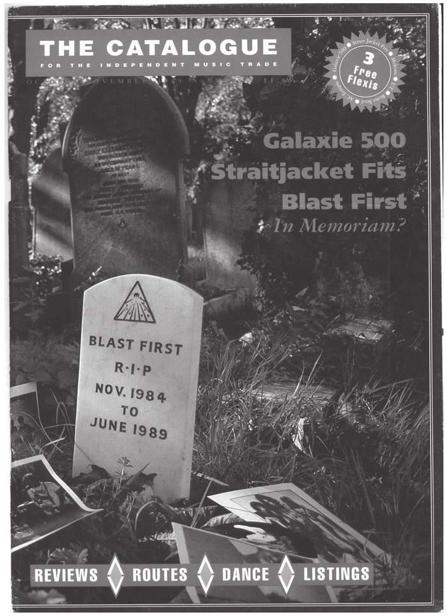

Cover of Rough Trade’s in-house trade paper,

The Catalogue

, October–November 1989 (

author’s archive

)

W

hen Rough Trade Limited went into administration in 1991 the news was met with a mixture of incredulity and resignation. While more hardened observers in the business had long assumed it was only a matter of time before the inevitable happened to a company run by amateurs, Rough Trade’s turnover in the late Eighties had been increasingly on the up. By 1989 the independent distribution sector – Rough Trade and its more successful and more orthodox rival Pinnacle, plus a handful of specialists – accounted for over 30 per cent of the music market. Rough Trade was, on paper, enjoying its most profitable period; following the no. 1 success of ‘Pump Up the Volume’ and ‘Doctorin’ the Tardis’, along with a series of Top Ten dance singles it was distributing, the company had shown itself capable of competing tooth and nail in the market.

Within Collier Street, despite the steady flow of chart-bound releases, it was becoming apparent that there were financial problems. Office Christmas parties were cancelled in 1989 and Richard Powell resigned, leaving the critical path in the hands of a new layer of management. If the London office was often volatile, the roots of the company’s demise lay further afield, in New York. Robin Hurley was running Rough Trade Inc., the American division of Rough Trade. As a former member of The Cartel he had an insider’s understanding of the company’s ethos and working methods which he had attempted to re-create in America.

‘When I moved to [the] USA in ’87 to run Rough Trade, it was in San Francisco,’ says Hurley. ‘It was really a shop and a wholesaler. It was run by a bunch of hippies and anarchists and it was really off the radar from what was going on in England. Rough Trade had had success in Germany, and there was an admittedly naive thought at Distribution, that, if we’re going to sign bands like The Smiths, we should have them worldwide and have them for the US, which at that point was half the world’s record sales. San Francisco had the best pot, was the nicest city in the USA to live in, as thought by a number of people in RT, and it was thought of as the right place to be. But when I lived there I realised, lovely though it is, it was something of a backwater both musically and in terms of the industry. For us to grow in the States we’d need an office in either New York City or Los Angeles. New York was closer to England there was more going on musically and we already had an office on the West Coast. So New York at that point was where the label happened: the A&R and the radio people and San Francisco was where the stock was held and distributed.’

Underestimating the size of the American market, which often required a chain of separate distributors to move stock from one coast to another and had a similarly fragmented media, Rough Trade did manage to successfully sign a number of American acts which gave the label a strong run of releases in its final years. Regularly spending time in New York, Travis’s downtown links remained strong. In 1987, to almost total indifference, he released

World of Echo

, Arthur Russell’s meditative tone poem for cello, voice, noise and filtered space,

*

one of the first records to address AIDS. Rough Trade’s release schedule featured

one-off

records by East Coast bands the Feelies and They Might Be

Giants; Travis also signed Boston’s Galaxie 500 to an album deal along with San Francisco’s Opal and the band who subsequently emerged from their demise, Mazzy Star.

‘Geoff was the driving force,’ says Hurley, who oversaw the bands’ domestic careers in the US. ‘Galaxie, Mazzy Star, along with Camper Van Beethoven and Lucinda Williams, were all signed in the USA. And we kept trying to grow the distribution in the States. I was in touch with Ivo and we licensed the first two Pixies records, the first Breeders record and the Wolfgang Press album for Rough Trade USA.’

Travis’s American signings were proof that, if the politics and internal arguments were destabilising the business at Collier Street, his A&R radar was still at its sharpest. The label hit a purple patch of critical approval and strong sales as Galaxie 500’s

Today

and

She Hangs Brightly

, Mazzy Starr’s debut, were both rapturously received in 1990.

Despite the label’s successes Travis was becoming aware that the company’s ongoing problems were getting more and more serious, though the extent of the seriousness and the lack of leadership within Distribution to address the problems was being kept from him. ‘From my point of view I was running the label,’ says Travis. ‘Although we had a proper distribution board, I was pretty much marginalised because the distribution people had an issue with the record company. They were jealous because I think they thought the record company was glamorous and my profile was the highest for whatever reason.’

Rough Trade had severely underestimated the running costs of a bicoastal American distribution and record company. Hurley was watching Rough Trade Inc. haemorrhage money and was continually having to call London to wire more and more funds to keep Rough Trade’s American division in business.

‘We were the biggest drain on Rough Trade trying to grow

in America,’ says Hurley, ‘trying to get over a certain point where sales would take care of themselves. The year we closed a distributor went under owing us a million dollars. Generally, in England people pay their bills, or in Germany they’re legally obliged to pay their bills. I would pick up the phone to London and say, “I think we’ve had our best month ever. We’ve just shipped x thousand records,” not realising that we might have to wait months to get paid. As our business grew the cash flow became crippled.’

In London a solution was found. The most successful of the Rough Trade distribution companies, Rough Trade Deutschland, would channel their payments to America rather than head office in London. What seemed like a good idea in the now permanently occupied Rough Trade meeting room was in fact illegal and illustrated the lack of technical expertise on the Rough Trade Distribution board.

‘There was a lot of money moving from Rough Trade Deutschland,’ says Hurley, ‘but the German government took a different view of it. Rough Trade Distribution was also suddenly hit by a big tax penalty, so those three things all hit at once. But Rough Trade America was the biggest single factor.’

Whatever the structures that had been put in place and the adherence, or not, to the critical path, the management’s lack of business skills ensured that the company was heading towards an inevitable conclusion. A sense of panic started to grip Collier Street, but in the short term the company, in a typical act of Rough Trade internalisation, was keeping its problems to itself.

‘I would go across every four months and sit in rather depressing meetings,’ says Hurley. ‘The writing was on the wall. There was a naive belief that we could pull through and we lost months with that sort of hope that something would come through. Warner Brothers showed an interest – they wanted 51

per cent and that was rejected. Arrogance is the wrong word. It was never arrogant, but it was a proud company that believed we had better music than other companies and the cultural philosophy was better. You were supposed to have a sabbatical after five years and as the company grew and got bigger that became harder – all those great ideas fell by the wayside.’

Many of those ideas had come from Richard Scott, who had left in 1988, dispirited that the idea of providing an alternative structure to the mainstream, which functioned around such ideas like de-centralisation and mutuality, had long been ceded to market share and competition. The Cartel, his lasting legacy, was disbanded in the summer of 1990. Two of its members, Red Rhino in Leeds and Fast Forward in Scotland, had already ceased trading. ‘I think I felt doomed,’ says Scott. ‘I felt that I was sort of, in a way, past my sell-by date. The actual structure that was evolving was one that I didn’t feel particularly comfortable with, which is why I decided to leave.’

The growing fiscal crisis at Rough Trade was finally starting to become common knowledge outside Collier Street. The production and release schedules of the smaller labels the company distributed were put on hold. Rough Trade’s biggest clients – Mute, KLF, 4AD, Beggars, Rhythm King and Jazz Summer’s Big Life, the latter being two dance pop labels with singles permanently on the radio and in the charts – were starting to realise the severity of the situation: Rough Trade had begun the long drawn-out process of going bust.

John Dyer was a young marketing executive at Mute who handled much of the label’s day-to-day dialogue with Rough Trade and became Daniel Miller’s eyes and ears as the situation at Collier Street started to unravel. ‘We were the last ones to know in a strange kind of way,’ he says. ‘There was an indie politeness. All these smaller labels were not getting paid and our

frustration was that we

were

getting paid. If we’d have known a bit earlier about the problems that were mounting up, maybe we could have gone in and actually taken control of it more. It’s all hindsight. I don’t think anyone would’ve run off to the majors at all. There was a system and that was the only system: there was Pinnacle and Rough Trade and Pinnacle was a very different sort of headspace for our little crew of labels.’

The endless meetings at Rough Trade – for so long a withering characterisation of the company – were now no longer populated by members of staff mediating each other’s in-house difficulties. An emergency committee was set up by Rough Trade’s

biggest-label

clients who were, they now realised, the company’s biggest creditors. Rather than Geoff Travis or the recently departed Richard Powell, a new face was chairing the meetings for Rough Trade: Powell’s replacement George Kimpton-Howe. Formerly of Pinnacle, Kimpton-Howe was a man, most of the staff at Rough Trade was convinced, who had been promoted well above his capabilities. As events started to take their course, it became clear he was not someone well equipped to handle a crisis.

‘We were suddenly presented with a cataclysmic moment rather than a moment that we could have all managed a bit better,’ says Dyer. ‘Suddenly Mute were faced with millions of pounds of losses as were The KLF, as were Beggars, as were Rhythm King. And from Rough Trade we were just encountering pretty fucking awful business strategy. There was a guy called George

Kimpton-Howe

, who felt the need to drive to work in a BMW, and people had trusted him because he took a Pinnacle philosophy into a bunch of indie kids and he was out of his depth.’

To make matters worse Rough Trade were in the middle of moving offices. A large open-plan office and warehouse building spread over five floors had been secured on Seven Sisters Road in Finsbury Park. Compared to the GLC-financed fit-out of Collier

Street, the Finsbury Park premises were a backwards step. The building was rickety and in disrepair. Once the workforce was relocated to Seven Sisters Road, while the lease was still to run on Collier Street, the first task Kimpton-Howe had to face was the process of dismissing them.

Travis, while present at the emergency comittee meetings, was keeping away from the increasingly tense winding-down processes of Rough Trade Distribution. The label still had a release schedule to honour and, while he had to make some of the record company staff redundant, he also hired a new label manager, Andy Childs. A former A&R who had signed Wire to the EMI subsidiary Harvest more than ten years previously, Childs was well versed in the realpolitik of the music industry. ‘As I was joining, loads of people had been made redundant,’ he says. ‘Geoff was just letting everyone go but at the same time he was looking at what he saw as the next phase of the label. My first week there I made myself scarce, because it was really an awkward situation. Everything moved to that big place in Finsbury Park, which was only temporary, while all the distribution side of it went into administration.’

Rough Trade now had to meet the running costs of two warehouses, Collier Street

and

Seven Sisters Road. Remarkably, a decision was taken to open a third warehouse in Camley Street, Islington, to accommodate all the overstocks of unsold vinyl that had accrued throughout Rough Trade’s trading history.

‘There’s this thing that label owners hate,’ says Dyer, ‘which is that they don’t like to destroy the stock … “Oh man, we might sell it next year … you know someone in Russia might buy it.” It’s absolute bunkum. What you end up doing is taking this stock around with you everywhere. So Rough Trade started paying for a multistorage warehouse, storing all our crap which we were too wimpy to destroy, because it’s sacrilegious to destroy vinyl.

So, suddenly, from having one warehouse they’ve got three, then it all catches up with them.’

As a metaphor for the failings and naivety of the independent sector, a warehouse leased purely for the purpose of housing its unsold and, by the outside world at least, unloved stock, is entirely apposite. The piles of records stacked up by employees working for cash-in-hand and a few guest-list favours are testament to the passion and folly and eternal optimism of the music obsessives who try and swim in the shark pools of the entertainment industry.

‘Kimpton-Howe didn’t realise about the housekeeping that was necessary,’ says Dyer. ‘It was all, “Let’s keep this going,” instead of thinking, “Let’s get rid of the warehouse and have a purge.” The sort of thing that’s common sense to a twelve-

year-old

was not being exhibited.’

Andy Childs was also aware that he was entering a company in its death throes that was being severely mismanaged. For someone who had experienced the manufacturing schedules and tightly controlled production capacities of a major label, the endless overflow of vinyl at Rough Trade was startling to witness. ‘Whoever was doing stock control was on another planet. That warehouse was full of unsold records and unwanted records, it was unbelievable. You’ve got this cavernous huge space and records had just been dumped. There was no business going on. It had just been frozen. It was like walking into this huge subterranean cavern with records put up and you’d walk around the corner and there’d be people in the dark, sifting through records. It was really odd, thousands and thousands of records, just dead stock lying there.’