How Music Works (31 page)

Authors: David Byrne

Tags: #Science, #History, #Non-Fiction, #Music, #Art

as with the early generation of CDs, I don’t think the technology was up to

the job yet. Those recordings have a slightly brittle quality that we might

have convinced ourselves was actually crystalline clarity. The excitement of using new technology also inspired everyone to believe that what we were

doing was important, of the moment, and top quality, just in case anyone

had any doubts.

As usual, I often improvised melodies to tracks that didn’t yet have any

melodies or words. The horn and string arrangements would be recorded after

I had these vocal melodies in place. Hernandez and other arrangers would

react to my wordless vocal melodies. Their horns and strings would fill in the gaps around the vocals and leave a musical space for them to be heard.

My singing style was inspired to change again, just as it had when we

recorded

Remain in Light

. The vaguely melancholy melodies over the syncopated grooves—typical of Latin music—was attractive as an emotionally lib-

erating combination. That the melodies and often the lyrics could be tinged

with sadness, but the buoyant music acted as a counterweight—a sign of

hope and an expression of life going on amid life’s calamities. The vocal

melodies and lyrics often hinted at the tragic nature of existence, while the rhythms and music said, “Wait—life is wonderful, sexy, sensual, and one

must persevere, and maybe even find some joy.” When it was time to record

the vocals, I began to sing in the studio with as much of that feeling as I

could muster, which maybe wasn’t all that much, given my background, but

it was the beginning of another big change for me. My daughter was born

around that time, so perhaps my evolving a more open singing approach

might have reflected this big change in my life.

With the help of Fernandez, I put together a live band, a fourteen-piece

orchestra, including Brazilian singer Margareth Menezes, for a world tour.

Near the end, in the middle of a South American leg, there was a bit of

170 | HOW MUSIC WORKS

trouble. Some of the percussionists left (pushing everyone to play in myriad styles had its limits), and they were replaced by Oscar Salas, a great Cuban drummer from Miami. He knew all the grooves from the various regions, so

it wasn’t as crazy a swap as it might have seemed. I realized that by adding a kit drummer, I could possibly make some music that fused the muscle of

funk and other styles with the lilt and swing of Latin grooves.

I didn’t forget that insight, and for my next record,

Uh-Oh

, I continued working with Salas, and I brought in George Porter, Jr., the incredible bass player from the New Orleans band the Meters, to work with us. Much Latin

music has a framework referred to as the

clave

(the key), which sometimes isn’t even played or audibly articulated by any one instrument. (What a

beautiful concept that is: the most important part is invisible!) The clave

divides the measures into a three-beat and a two-beat pattern—for rock-

ers it’s like a Bo Diddley beat, or the Buddy Holly song “Not Fade Away.”

(Rock and roll didn’t just come from country and blues mixing; there was

Latin flavor in there, too!) All the other parts, even the horns and the vocals, acknowledge the clave pattern and play with awareness of it, even if it isn’t always audible.

I heard an undercurrent of clave in the New Orleans funk that the Meters

made famous, which is not surprising given that city’s waves of immigra-

tion from Cuba and Haiti. I thought George might help me find a way to

create a hybrid out of Latin grooves and the funk he was accustomed to.

By now I was a little more familiar and comfortable with some of those

grooves, and I felt I could let things move into uncharted and undefined

territory. The rhythms didn’t have to be restricted to only one genre. I

didn’t feel the need to have Milton or José determine how a song would go

on this project; I more or less knew when I was writing the songs what the

rhythms would be.

I asked the Brazilian musician Tom Zé to do the arrangement for one

of these songs, “Something Ain’t Right.” The groove was based on an ijexa

rhythm, which is usually played on cowbells and is often associated with

Candomblé, the Afro-Brazilian religion. The groove is featured in a number

of songs by artists from Salvador, in Brazil’s Bahia region, so I knew Tom

would be familiar with it. He did some wonderful horn arrangements, but

then he surprised us all by pulling out some Bic pens, minus the ink car-

tridges, and passing them out to the horn players. Each plastic penholder

DAV I D BY R N E | 171

had a thin little piece of plastic taped to the end, which functioned like

a reed on a saxophone or clarinet. He had an arrangement all worked out

for these guys to play the pens in one section of the song. It wasn’t just

noise, either. He had them play a hocket pattern, where each player plays

just one note, quickly, and by deciding which players played what, and when, an intricate pattern resulted. It was brilliant. Only Tom Zé would have had

the nerve to ask these New York session guys to play Bic pens.

BACK TO THE BEGINNING

In 1993, I wanted to write some songs that were more stripped down, and

to foreground their emotional content. I sensed that if the horns and

strings and multiple percussionists were stripped away a bit, then what I

was singing about might communicate more directly. Maybe I had been get-

ting carried away with the window dressing. This emphasis on a thoroughly

personal kind of writing was a big change for me, and it was possibly as

much in response to a recent death in the family as it was musical evolution.

I wanted to jettison everything, to start from scratch. I had heard Lucinda

Williams and my friend Terry Allen, and I wanted to write songs that

seemed to come from the heart as much as theirs did. Writing from expe-

rience went against the grain for me, but I wanted to let the lyric content

dictate the music a little more. I had the concept, though not the same

instrumentation, of traditional jazz combos in mind. Musically I might have

been inspired by the recent rise of the improvisation scene around the old

Knitting Factory on Houston Street. I liked the idea of a small ensemble that listened to and played off each other and whatever the lead instrumentalist

or vocalist was doing. So I wrote the songs, and instead of going straight

into a recording studio, I put together a small band and performed them live, in small clubs.

The songs and their arrangements began to gel as they were tested in

front of live audiences. The plan was to more or less record the band playing live in the studio relatively soon, as I had an image in my mind of classic

small-ensemble jazz recordings, with all the musicians more or less in a

circle in the middle of a studio—a re-creation of a club stage or bandstand.

A situation in which everyone could hear and see everyone else, very old

172 | HOW MUSIC WORKS

school. I hoped that after having done some live shows, the band would

know the arrangements and would play each song as if it were second nature,

an old friend.

It didn’t work out that way. A band member was fired, producers came

and went, the whole plan fell to pieces. But the core group—the rhythm

section of Todd Turkisher and Paul Socolow—survived. The fairly stripped

down and bared-soul aspect of that

David Byrne

record managed to allow me an escape from the musical cage I’d made for myself. I’d just recorded and

toured with two very large, Latin-inspired bands, and as much as I loved

that experience, I could tell I was being branded as the rocker who had abandoned the cause. This new record did feel like a fresh start, even though it was born out of death and thwarted plans.

THE STUDIO COMES HOME

By the late nineties, new audio technology had emerged that allowed

musicians to make professional-caliber recordings in their home stu-

dios. I bought a little mixing board and a couple of DA-88 machines, which

used Hi-8 video cassettes to record eight tracks of good-quality digital

audio. Other companies came out with other machines. The ADAT devices

used super-VHS videocassettes, which were cheaper than the Hi-8 cas-

settes, so more musicians adopted these for their home studios. They often

synched the recorders to midi devices too, so as tape rolled, the sampler or other devices could be instructed to play pre-determined notes or drum

samples along with the recorded tracks. Cheap Atari computers sometimes

entered the picture as well. They had software that allowed you to make

visual representations of these midi sequences which would then be used to

trigger beats (typically), samples, and synthesizers. A whole song arrange-

ment could be created without actually playing anything, and without the

need for recording tape. With this gear one could see that the need for an

expensive recording studio was beginning to become superfluous.

DAV I D BY R N E | 173

TECH TALK

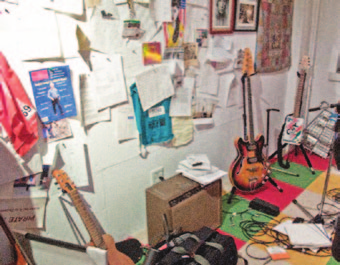

These days I work in a home studio, which I’ve carved out of the larger

room you can see on the bottom of this page.I Tidy, eh? Embarrassing,

actually.J

There is no professional sound-absorbent baffling here as there might be

in a professional recording studio, but the floors of this former industrial building are concrete, so sound doesn’t really escape and bother the neighbors. I put industrial carpet down, and one wall is covered with a kind of

sound-absorbent sheetrock, so I’ve taken some precautions to prevent sound

leaking out. Unwanted sound coming in can be an issue too, but unless a

truck backfires outside or an ambulance goes by, I’ve found that it is perfectly adequate, at least for recording vocals and guitars. There’s no space in my

room for drums or anything like that, but for writing, playing one instrument, programming, and singing, it’s fine. There’s a good tube microphone, another mic for a little old guitar amp, and a nice preamp and compressor to massage the mic signals before they become ones and zeros. That’s pretty much all

you need to find out where a song wants to go and, I’ve found, even enough to record real vocals and some guitar parts.

Serial numbers and security codes for software are pinned to the wall, along with a Tammy Wynette poster. The computer is tucked under the desk. It’s a

mess, but amazingly, this is how we make records now.

Home-studio recordings can now sound as good as the big-name studios,

and the lower pressure (and less expensive) vibe in a home environment is

often more conducive to creativity. Home recordings can be used for more

than just demos. This idea is somewhat revolutionary as far as recording and

I

J

composing music goes, and the repercussions of these baby steps will be huge further down the road.

By 1996, I’d written some new songs, which arrived in a wide variety of

styles—maybe because I wasn’t writing for a specific band anymore. It seemed to me that the songs would best be interpreted by either different musical

groups or by a single group pretending to be a variety of groups. For most of this record, I chose the former, deciding to record the material by inviting a lot of musicians and producers I liked to perform and record specific songs.

Judicious casting of these collaborators, who would also be creative produc-

ers, helped me get the variety I felt the songs were asking for. I worked with Morcheeba at their studio in London, with the Black Cat Orchestra in Seattle, with Devo at their studio in LA, with Joe Galdo in Miami, with Hahn Rowe