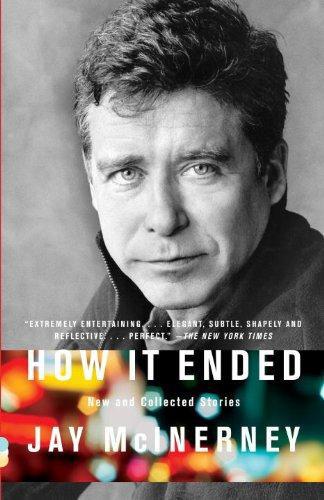

How It Ended: New and Collected Stories

Read How It Ended: New and Collected Stories Online

Authors: Jay McInerney

Tags: #General, #Literary, #Fiction, #Short Stories, #Fiction - General, #Short Stories (Single Author), #Jay - Prose & Criticism, #Mcinerney

Also by Jay McInerney

NONFICTION

A Hedonist in the Cellar

Bacchus and Me

FICTION

The Good Life

Model Behavior

The Last of the Savages

Brightness Falls

Story of My Life

Ransom

Bright Lights, Big City

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

Copyright © 2009 by Bright Lights, Big City, Inc.

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by

Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc., New York,

and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

Knopf, Borzoi Books and the colophon are

registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

The following stories originally appeared in book form in

Model Behavior:

A Novel and Stories

(New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1998): “The Business,”

“Con Doctor,” “Getting in Touch with Lonnie,” “How It Ended,” “The Queen

and I,” “Reunion” and “Smoke.” These stories, along with “My Public Service,”

“Simple Gifts” and “Third Party,” were subsequently published in Great Britain

in the collection

How It Ended

(London: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 2000).

Some stories were previously published in the following: “Putting Daisy Down”

in

The Guardian Literary Supplement

, “The Madonna of Turkey Season” in

Image

(Dublin), “The Last Bachelor” in

Playboy

and “Everything Is Lost” in

The Sunday Times Magazine

(London).

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

McInerney Jay.

How it ended : new and collected stories / by Jay McInerney. — 1st ed.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-307-27152-5

I. Title.

PS3563.C3694H69 2009 813′.54—dc22 2008053518

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents either are the

product of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to

actual persons, living or dead, events or locales is entirely coincidental

.

v3.0

For Barrett and Maisie

PREFACE

Like most novelists I cut my teeth writing short stories, and that's one habit I've never been able to break. I was lucky enough to study under two masters of the form, Raymond Carver and Tobias Wolff, who were both teaching at Syracuse University when I showed up in 1981 after being fired from

The New Yorker

for being a very bad fact-checker. Like the Talking Heads, I believed that facts all came with points of view. Whether or not I was correct to conclude that fiction was my métier, I clearly couldn't be trusted with the facts.

In fact, I'd gone to Syracuse specifically to study with Carver, whose writing I'd revered ever since I read

Will You Please Be Quiet, Please?

not long after it came out in 1976. I was lucky enough to get Wolff, who had just published

In the Garden of the North American Martyrs

, in the bargain. As a teacher, Ray operated on intuition: He saw himself as a nurturer rather than a critic. His greatest gift was to foster the inner editor in each of us, questioning word choice, querying what he considered pretentious verbiage, underlining or crossing out questionable adjectives and sprinkling question marks in the margins. Besides presiding over workshops, he taught a course called “Form and Theory of the Short Story,” in which we read his favorite practitioners: Chekhov, Babel, Hemingway, Welty and the O'Connors, Frank and Flannery. At the beginning of each class he would light up a cigarette and ask, “So, what did you think?” Ray's idea of a good session was one in which these were the last words he spoke. When a student from the English department proper challenged him about this methodology, demanding to know why the class was called “Form and Theory” when there was little of either, Ray nervously sucked on his cigarette and hunched lower in his chair. “Well,” he said after a very long pause, “I guess it's like we read the stories … and then form our own theories.”

Toby was far more analytical, and more critical. He would disassemble a short story before our eyes like a forensic pathologist, labeling the various components and explaining how they worked or, as was the case with most of our workshop submissions, why they didn't. Unlike his distinguished colleague, he didn't suffer fools, or their stories, gladly.

At Syracuse I wrote “In the North-West Frontier Province,” which I sent to

The Paris Review

. A few weeks later I was astonished to receive a phone call from George Plimpton, its longtime editor, who told me, in that silvery patrician voice, he quite liked the story and was inclined to publish it but wondered if I possibly had anything else to show him. After rereading my old stories and realizing that they were all pretty much derivative crap, I found a paragraph written in the second person that I'd scrawled after a disastrous night on the town. This struck me as more original, and subsequently I stayed up all night writing “It's Six A.M. Do You Know Where You Are?”—which became my first published story when George brought it out in 1982. At some point I realized I had more to tell about this particular character in this particular voice, and the story became the basis for my first novel,

Bright Lights, Big City

. “In the North-West Frontier Province” eventually found a place, as a kind of backstory, in my second novel,

Ransom;

since it seems to me my first successful story, I've included it here.

My next novel,

Story of My Life

, grew rather more organically out of a short story published under the same title in

Esquire

in 1987. Likewise, “Philomena,” published in

The New Yorker

in 1995, later evolved into the novel

Model Behavior

. (Not included here is “Savage and Son,” published in

Esquire

in 1993, which became the basis for my novel

The Last of the Savages

, because it seems to me a novella rather than a short story—a question not merely of length but of scope.)

Clearly, I was attracted to the long form, and my short stories—some of them, at least—often turned out to be warm-up exercises. There's psychological as well as practical value in using one as a sketch for a novel; the idea of undertaking a narrative of three or four hundred pages, which might consume years of your life, is pretty daunting. A novel's a long-term relationship. Sometimes it's easier to pretend you're engaging in a one-night stand and see how it feels.

On the other hand, at the risk of contradicting myself, I have always been more than a little daunted by the short story. Whereas even a medium-sized novel—let alone the kind Henry James described as a loose baggy monster—can survive any number of false turns, boring characters and off-key sentences, the story is far less forgiving. A good one requires perfect pitch and a precise sense of form; it has to burn with a hard, gemlike flame.

“Smoke” was written in 1985, shortly after the publication of

Bright Lights, Big City

. It was the first outing for Russell and Corrine Calloway, who have reappeared in

Brightness Falls

and

The Good Life

. In between novels I have continued to write stories, seven of which were published in hardcover in 1999 along with the short novel

Model Behavior

, but since they did not appear in the paperback edition I have included them here: “Smoke,” “The Business,” “How It Ended,” “Getting in Touch with Lonnie,” “Reunion,” “The Queen and I” and “Con Doctor.”

It's strange how the retrospective view highlights the temporal signature of certain stories. “My Public Service,” which I somehow forgot to include in

Model Behavior

, was written in 1992, years before Monica Lewinsky became a household name. “The Queen and I” was written at about the same time, when the Meatpacking District was still the center of the industry for which it was named by day, and by night devoted to another kind of meat altogether and populated largely by transsexual streetwalkers and their cruising johns. Those familiar with its current incarnation as Manhattan's glossiest hub of platinum-card nightlife might have a hard time recognizing it here. And speaking of change—I saw no reason not to tinker with these older stories when I thought they might be improved. Nor did I feel compelled to resurrect several stories which seemed, on reflection, to resemble sleeping dogs.

The twelve most recent stories, including “Sleeping with Pigs,” “Invisible Fences,” “I Love You, Honey,” “Summary Judgment,” “The Madonna of Turkey Season,” “The Waiter,” “Everything Is Lost,” “The Debutante's Return” and “Putting Daisy Down,” were composed in something of a sprint from December 2007 through the late spring of 2008. “Penelope on the Pond,” which features Alison Poole, the protagonist of my 1988 novel

Story of My Life

, was also written during this period. (Alison has enjoyed an interesting career as a fictional character: Bret Easton Ellis borrowed her for

American Psycho

, where she narrowly avoids getting murdered by Patrick Bateman, and she subsequently assumed a prominent role in his novel

Glamorama

. Moreover, the woman who inspired this character has recently achieved a certain real-life notoriety, but that's a factual matter which needn't further concern us here.) Corrine Calloway returns in “The March,” which I wrote while I was working on

The Good Life

. And the most recent story here, “The Last Bachelor,” was finished in May of 2008, though the first few paragraphs were written in the early nineties and then set aside.

As different as these twenty-six stories—written over the last twenty-six years—might be, certain preoccupations and obsessions seem to have endured. But enough of these damn facts. I enjoyed writing these stories, and hope you enjoy reading them.

Jay McInerneyAugust 2008

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

It's probably impossible to acknowledge all of those who have helped inspire, improve and meddle with these stories, written over a span of twenty-six years. Still, it would be ungrateful not to try. Special thanks to George Plimpton for saving me from law school by publishing my first short story, and to Raymond Carver and Tobias Wolff for reading and commenting on numerous unpublished narratives that preceded it. Bill Buford, as editor at

Granta

and later

The New Yorker

, helped shape and polish several of these stories. I owe a debt of gratitude as well to Rust Hills, who nurtured and published many installments of my fiction during his tenure at

Esquire

, and to Alice Turner, former fiction editor at

Playboy

. Mona Simpson, Bob O'Connor, Donna Tartt, Julian Barnes, Helen Bransford, Terry McDonell, Bret Easton Ellis, Virginia O'Brien, Jon Robin Baitz and Anne Hearst McInerney are among the early readers who have helped to improve these stories. And I feel very lucky and blessed to have had Binky Urban as a reader and an adviser since the start of my career. Finally, Gary Fisketjon has been my closest reader for thirty years, since we were classmates at Williams College. I showed him my earliest stories not long after we exchanged blows in the name of a romantic rivalry. He's read every line of fiction I have written since then, and I've benefited immeasurably from his advice, even if some of his criticism has reminded me of his right jab.