How Does Aspirin Find a Headache? (25 page)

Read How Does Aspirin Find a Headache? Online

Authors: David Feldman

Flight paths are usually determined by visual, auditory, or olfactory stimulation. For example, bees and butterflies orient to the color and size of flowers; dragonflies orient to their prey items; moths orient to a wind carrying a specific smell, usually a “pheromone.”

Submitted by Dallas Brozik of Huntington, West Virginia

.

What’s

the Difference Between “French” and “Italian” Bread?

Not a whole lot, it turns out. But there are enough differences in ingredients to account for the subtle differences in taste and, particularly, texture.

Baking consultant Simon Jackel kindly wrote us a primer on the subject:

French and Italian breads are made from the same basic ingredients: flour; water; salt; and yeast. Both use “strong” flours. And they both develop crisp crusts in the oven due to the injection of live steam.

But there the similarity ends, because “French” breads, but not “Italian,” also incorporate small amounts of shortening and sugar in the formulation. The effect of these additional ingredients is to allow the French dough to expand more and become larger in volume, lighter in consistency, and more finely textured in the interior. In contrast, Italian breads are denser and less finely structured in the interior.

The shape of the loaf may tip off the nationality of the bread. Sometimes, “Italian” bread is formed in a football-like shape, as opposed to the sleeker “French.” And sometimes “Italian” bread is topped with sesame seeds, an embellishment that would probably make the French pop their berets.

Submitted by Todd Kirchmar of Brooklyn, New York

.

Why

Have So Many Pigeons in Big Cities Lost Their Toes?

The three main dangers to pigeons’ toes are illnesses, predators, and accidents. Pigeons are susceptible to two diseases that can lead to loss of toes: avian pox, a virus that first shrivels their toes to the point where they fall off, and eventually leads to death; and fungal infections, the price that pigeons pay for roaming around in such dirty environments.

Nonflying predators often attack roosting pigeons, and the toes and lower leg are the most vulnerable part of pigeons’ anatomy. Steve Busits, of the American Homing Pigeon Fanciers, told

Imponderables

that “Rats or whatever mammal lives in their habitat will grab the first appendage available.”

Accidents will happen, too. Busits says that toes are lost in tight spaces, namely “any cracks or crevices that their toes can become stuck in.” Bob Phillips, of the American Racing Pigeon Union, adds that toes get lost while pigeons are in flight, with television antennas and utility wires being the main culprits.

Submitted by Nancy Metrick of New York, New York. Thanks also to Jeanna Gallo of Hagerstown, Maryland

.

How

Do Highway Officials Decide Where to Put a “Slippery When Wet” Sign?

The holy grail of signage policy is the

Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices

, a Federal Highway Administration publication that is followed by state jurisdictions as well. In other

Imponderables

books, we’ve regaled you with complex descriptions of how the MUTCD specifies exactly where, how, and why certain traffic signs should be posted.

But the MUTCD passage on “Slippery When Wet” signs is remarkably vague by comparison:

The Slippery When Wet sign is intended for use to warn of a condition where the highway surface is extraordinarily slippery when wet.

It should be located in advance of the beginning of the slippery section and at appropriate intervals on long sections of such pavement.

Without specific instructions, state highway agencies have to decide where to place signs.

So how do they decide what roadways are slippery?

1. According to Harry Skinner, chief of the traffic engineering division of the Federal Highway Administration’s Office of Traffic Operations,

Highway surface will become extraordinarily slippery if the aggregate or rock in the pavement becomes polished and cannot drain off all water with which it comes in contact.

Obviously, all surfaces are more slippery when wet than when dry, and a roadway shouldn’t be slapped with a “Slippery” sign merely because it becomes slick when ice accumulates. In fact, specific “Icy Pavement” signs are available to warn about these conditions. Sometimes, “Slippery” signs are erected precisely because the roadway looks innocuous; one state document we read indicated that a “Slippery When Wet” sign should be placed where “skid resistance is significantly below that normally associated with the particular type of pavement, or where there is evidence of unusual wet pavement.”

2. Bridges tend to be more slippery than adjacent pavements and may warrant a sign.

3. If a roadway is suspected of being slippery, engineers can do a technical analysis, determining the “coefficient of friction.

4. But the most common motivation for placing a “Slippery When Wet” sign is a little more depressing, as Joan C. Peyrebrune, technical projects manager of the Institute of Transportation Engineers, explains:

Generally, signs are placed at locations where an accident analysis indicate that a significant number of accidents caused by slippery conditions has occurred. The number of accidents that warrant a “Slippery When Wet” sign varies for each state.

This strategy reminds us of an old cartoon we found in a sick joke book: As an automobile pileup of epic proportions turns an intersection into a scrap-strewn catastrophe, an expressionless policeman mounts a ladder to place an “out of order” sign over a failing traffic light.

The intent of the “Slippery When Wet” sign is no different from the “Falling Rock” sign we talked about in

When Did Wild Poodles Roam the Earth?

The hope is that the driver, fearing impending doom, will slow down a tad. And maybe now that you know that these notices serve as markers for misguided drivers who once veered off the road, the signs will do their jobs even more effectively.

Submitted by Herbert Kraut of Forest Hills, New York

.

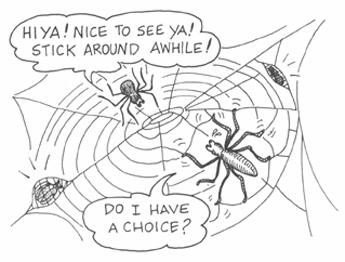

Yes, spiders get caught in the webs of other spiders frequently. And it isn’t usually a pleasant experience for them. Theoretically, they might well be able to navigate another spider’s web skillfully, but they are rarely given the choice. Spiders attack other spiders, and, if anything, spiders from the same species are more likely to attack each other than spiders of other species.

Most commonly, a spider will grasp and bite its intended victim and inject venom. Karen Yoder, of the Entomological Society of America, explains, “Paralysis from the bite causes them to be unable to defend themselves and eventually they succumb to or become a meal!”

Different species tend to use specialized strategies to capture their prey. Yoder cites the example of the Mimetidae, or pirate spiders:

They prey exclusively on other spiders. The invading pirate spider attacks other spiders by luring the owner of the web by tugging at some of the threads. The spider then bites one of the victim’s extremities, sucks the spider at the bite, and ingests it whole.

The cryptic jumping spider will capture other salticids or jumping spiders and tackle large orb weavers in their webs. This is called web robbery.

Other spiders will capture prey by grasping, biting, and then wrapping the victim with silk. Leslie Saul, Insect Zoo director of the San Francisco Zoo, cites other examples:

Others use webbing to alert them of the presence of prey. Others still have sticky strands such as the spiders in the family Araneidae. Araneidae spiders have catching threads with glue droplets. The catching threads of Uloborid spiders are made of a very fine mesh (“hackel band”).

Dinopis

throws a rectangular catching web over its prey item and the prey becomes entangled in the hackle threads.

Saul summarizes by quoting Rainer F. Foelix, author of

Biology of Spiders

: “The main enemies of spiders are spiders themselves.”

Not all spiders attack their own. According to Saul, there are about twenty species of social spiders that live together peacefully in colonies.

Submitted by Dallas Brozik of Huntington, West Virginia

.

Over the years, we have received many Imponderables about McDonald’s but have found answers elusive. Now, with the help of Patricia Milroy, customer satisfaction department representative, we can finally unburden you of some of your obsessions.

To

Exactly What Is McDonald’s Referring When Its Signs Say “Over 95 Billion Served”?

This Imponderable has provoked more than one argument among our peers. We’re proud to finally settle the controversy. No, “95 billion” does not refer to customers served, sandwiches served, food items served, or even hamburgers served.

The number pertains to the number of

beef patties

served. A hamburger counts as one patty. A Big Mac counts as two. A quarter-pounder with cheese counts as one. A double cheeseburger counts as two. Got it? The practice undoubtedly started when McDonald’s served no other sandwiches besides (single-patty) hamburgers and cheeseburgers.

By the time you read this, McDonald’s will have “turned over” the sign and added another digit. Expectations are that the corporation will have sold 100 billion beef patties before the end of 1993.

Submitted by Jena Mori of Los Angeles, California

.

Why

Are McDonald’s Straws Wider in Circumference Than Other Restaurant or Store-Bought Straws?

McDonald’s has test-marketed numerous sizes and materials for their straws. Milroy says:

After working with our suppliers and testing them with our customers, we’ve found that the present size of our straws is preferred by the majority of our customers.

One of the readers who posed this question guessed the key to the wider circumference of McDonald’s straws—many, many milkshakes get sold at the Golden Arches. Any fan knows of the frustration of trying to suck up a thick glop of milkshake through a narrow straw: liquid gridlock. Sure, Mickey D’s might give us more straw than we need for Coca-Cola, iced tea, or milk, but when we choose milkshakes, the bigger the better.