How (26 page)

Authors: Dov Seidman

I had an even more powerful reason to take off my Master of the Universe suit and open up to Alan. Vulnerability creates true opportunities for deep collaboration, a much more profitable relationship than just making money. Being transparent with him created a moment that made it clear that I thought Alan was more valuable than the money he could potentially invest. After all, in the same way I want my journey and the journey of LRN to be more significant than just our bottom line, Alan wants to be more than just a money man. The opening I extended allowed him to see an opportunity to pursue his own journey of significance, to share his knowledge and wisdom in a more substantive way. Instead of just showing him a bright shiny wheel, I showed myself as a gear, with powerful teeth but also with spaces into which he could intermesh. My transparency gave him a vision of what we could accomplish together in one machine, to create an intimate collaboration that had the potential to set off an upward spiral of meaningful endeavor. Not long after, Alan and Polaris did invest in LRN, and I asked him to sit on our corporate board, where he is now an integral part of who we are.

What does it mean to be truthful? To be open? To act from principle rather than for a desired effect? For one thing, it’s simpler. As Mark Twain once wrote, “If you tell the truth you don’t have to remember anything.”

41

More importantly, in a world accustomed to falsehood and deception, in which daily we receive hundreds of commercial messages inveigling us to one act or another, transparency and forthrightness can be tremendously refreshing. No one can copy your HOWS, and within the wide spectrum of human behavior, the HOW of active interpersonal transparency can become a powerful differentiator.

DOING TRANSPARENCY

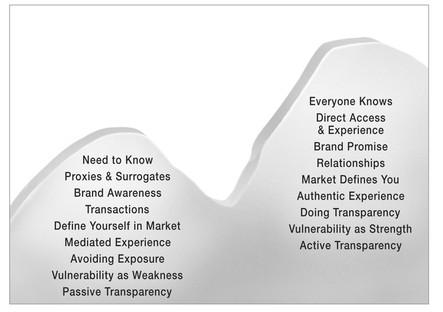

The Certainty Gap does not just describe a condition of the world; it also describes our relationship with those around us in business. There is a Certainty Gap between people, too. Business relationships are formal relationships, and just like companies use programs or advertising as formal layers between themselves and their market, people rely on personal surrogates and proxies in their dealings with others each day. When a buyer in a negotiation tells a potential vendor, “We’re talking to your competitors,” when it isn’t true, the buyer is using the illusion of false action to secure a better price. When a boss says, “Get it to me by four o’clock,” without sharing the reasons and benefits of the action, the boss is relying on the proxy of his or her position to get things done. When the world is opaque and you can’t see beyond people’s personal proxies, there is a Certainty Gap in your interactions with them. But when active transparency is in the room and people show you what’s behind the curtain, it raises the floor, the Gap is smaller, and the conditions that breed the trust you need to fill it rush in. The conditions of general uncertainty in the world make transparency—both technological when you can turn it to your favor and interpersonal when you can bring it to the table—into one of the most powerful HOWS there is.

CHAPTER

8

Trust

For it is mutual trust, even more than mutual interest

that holds human associations together. Our friends

seldom profit us but they make us feel safe.

—H. L. Mencken

A

few years ago, in the early days of the blogging phenomenon, a New York-based web designer named Jason Kottke told a fascinating story on his blog,

Kottke.org

, about his experience with a coffee-and-doughnuts street vendor he called Ralph.

“I stepped up to the window, ordered a glazed donut (75 cents),” Kottke writes, “and when he handed it to me, I handed a dollar bill back through the window. Ralph motioned to the pile of change scattered on the counter and hurried on to the next customer, yelling ‘Next!’ over my shoulder. I put the bill down and grabbed a quarter from the pile.” Kottke was intrigued by this behavior, so he decided to investigate. “I walked a few steps away and turned around to watch the interaction between this business and its customers. For five minutes, everyone either threw down exact change or made their own change without any notice from Ralph; he was just too busy pouring coffee or retrieving crullers to pay any attention to the money situation.”

1

As he observed and considered what may be gained or lost by this unusual policy, Kottke noticed that Ralph was serving an extraordinary number of customers. To confirm this suspicion, he went and watched two other similar vendors nearby. On average, both spent twice as much time with each customer and served half as many in a given time period.

Kottke is no economist, but it was immediately apparent to him “that Ralph trusts his customers, and that they both appreciate and return that sense of trust (I know I do).” He also noticed something that often eludes us. “When an environment of trust is created,” he writes, “good things start happening. Ralph can serve twice as many customers. People get their coffee in half the time. Due to this time-saving, people become regulars. Regulars provide Ralph’s business with stability, a good reputation, and with customers who have an interest in making correct change (to keep the line moving and keep Ralph in business). Lots of customers who make correct change increase Ralph’s profit margin. Etc. Etc.”

Kottke observed, in a firsthand anecdotal way, a quantification of trust in action. Because Ralph trusts his customers to make honest change, he is able to serve far more of them than his competitors serve. In economic terms, Ralph reduced his transaction costs by substituting trust for the labor of making change. A cost-benefit analysis would probably reveal that what he loses in dishonesty or error he more than makes up for in gross sales volume. Additionally, although increased volume results in less of the person-to-person service time that you would suspect is necessary to build customer loyalty, Ralph’s customer loyalty seems anecdotally to have increased. The introduction of trust had an unintended consequence for his business: It made customers more likely to get their daily doughnut fix from him rather than his competitor down the block.

Trust is a funny thing, one of those soft things that we often rush by. What’s not so funny is how often it lies at the center of our challenges and opportunities. “Trust is like the air we breathe,” Warren Buffett said. “When it’s present, nobody really notices. But when it’s absent, everybody notices.”

2

That is because trust allows us to function in times of uncertainty. When the Certainty Gap—that space between the unpredictable nature of the world and our ideal vision of stability—grows, we look for something to fill it. That something is

trust

. Trust calms the fears that uncertainty breeds. In times of high uncertainty, therefore, we pay more attention to the source of trust: human conduct—HOW we do what we do. Trust becomes, more vitally than ever, the currency of human exchange.

Business has long known about the benefits of trust, but absent any real metrics or data found itself at a loss to be able to do anything about it. Similarly, we as individuals innately seek trusting environments and trusting relationships in order to enrich our lives, although we often don’t give much conscious thought to how to create them.

THE SOFT MADE HARD

We have two ways of calculating the value of trust: subjectively (how it makes us feel) and objectively (in dollars and cents). Subjectively, almost all of us would rather live and work in a world where the Certainty Gap is filled with trust, predictability is high, and we feel safe and secure. So we accept prima facie that trust plays an important role in the way we live our lives. Trust makes us feel safe. It allows us to function and thrive in an uncertain world. To fully understand the value of trust in business, however, we must begin to quantify it objectively, to move it from the realm of feelings to the realm of observable benefit. Trust, for instance, allows us to rely on each other, to divide up labor and form teams knowing that each will do his or her part, and to share confidences with others. Without trust, how could you send a confidential strategy e-mail to a partner and know that it will remain confidential? Business, for its part, has long suspected that trust could, in fact, be objectively quantified, but it is only recently that researchers have done so. Their findings reveal a startling truth: Trust, to use an old cliché, makes dollars

and

sense.

In a groundbreaking 2002 study, Professors Jeffrey H. Dyer of the Marriott School at Brigham Young University and Wujin Chu of the College of Business Administration at Seoul National University proved empirically what the blogger Jason Kottke observed on the streets of New York. Dyer and Chu surveyed almost 350 buyer/supplier relationships involving eight automakers in the United States, Japan, and South Korea and found a direct, and dramatic, relationship between trust and transaction costs. The least trusted buyer incurred procurement costs

six times

higher than the most trusted: same parts; same sorts of transactions;

s

ix times more expensive. These additional costs came from the added resources that went into the selection, negotiation, and compliance costs of executing deals. Dyer and Chu point to Nobel Prize-winning economist Douglass C. North’s findings that these sorts of transaction costs account for more than a third of all business activity They also found, perhaps to no surprise, that the least trusted companies were also the least profitable.

But Dyer and Chu didn’t stop there. They also studied the relationship between trust and certain value-creating behaviors, specifically the willingness to share critical information among business partners. Though it was unclear, in a chicken-or-the-egg sort of way, which led to which, their data clearly demonstrates that trust extended by one company to another increases value-creating behaviors, like information sharing, which, in turn, leads to higher levels of trust. One executive they interviewed put it like this:

We are much more likely to bring a new product design to [high-trust Automaker A] than [low-trust Automaker B]. The reason is simple. [Automaker B] has been known to take our proprietary blueprints and send them to our competitors to see if they can make the part at lower cost. They claim they are simply trying to maintain competitive bidding. But because we can’t trust them to treat us fairly, we don’t take our new designs to them. We take them to [Automaker A] where we have a more secure long-term future.

3

Like the oxytocin response between one person and another, trust between companies leads to more trust. It sets off an upward spiral of cooperative, value-creating behaviors. “This phenomenon makes trust unique as a governance mechanism,” Dyer and Chu conclude, “because the investments that trading partners make to build trust often simultaneously create economic value (beyond minimizing transaction costs) in the relationship.”

I was struck by these stories about transactions both small, like Ralph’s doughnuts, and medium-sized, like Dyer and Chu’s study, but I wondered if the same principles applied at the highest levels of business and the biggest deals. This reminded me of a story told to me by Mike Fricklas, executive vice president, general counsel, and secretary of Viacom Inc., one of the largest media conglomerates in the world, when we met recently at Viacom’s headquarters in Times Square. After a successful career in mergers and acquisitions (M&A), Fricklas came to Viacom to negotiate their purchase of Paramount and Blockbuster, two of the biggest media deals of the 1990s. Since then, he has played a central role in Viacom’s growth and acquisitions. Mike and I have worked together for many years, and I have found him not just a first-rate lawyer, but a true adviser to those at the highest levels of business. So I asked him how trust factors into the work he does every day. “Transaction costs are not such a big deal in large commercial transactions,” he told me. “What’s much more strategic is if people want to do business with you in the first place.”

4

When we spoke, Mike confessed that Viacom was currently pursuing a strategy of modest-sized acquisitions, but pointed out what he felt was a significant advantage that Viacom, by virtue of its square dealing, enjoyed. “People trust us enough that at the beginning of the relationship, when we first reach out to potential acquisition targets, we’re getting a series of exclusivities—in effect, ‘trust me’s’—where companies are taking themselves off the market because they want to move forward with us.”

This is an example of how existing trust can fill the Certainty Gap between two companies, especially when one is the target of an acquisition and may have a lot to lose. Obviously, having an exclusive, first-look opportunity to transact business represents a significant advantage in the marketplace. But it is another soft, anecdotal example of the value of trust, and I wanted to know if Mike could make a direct connection between trust and profit at the highest levels of business. “Absolutely,” he immediately replied. “In economic terms, trust is important to the cost of capital. When you need money to finance a large deal, you often can’t clue the market in to the exact specifics of your business plan without compromising your competitive advantage. So the market relies on trust and your past consistency. With trust, they lend you money at a lower rate. So a multibillion-dollar transaction will close at a lower price when you are a preferred partner, rather than going to the stock market and paying with the same green as everyone else.”