House of Hits: The Story of Houston's Gold Star/SugarHill Recording Studios (Brad and Michele Moore Roots Music) (14 page)

Authors: Roger Wood Andy Bradley

Tags: #0292719191, #University of Texas Press

Miller followed up with several other Starday singles, including “Family Man” (#457), which charted as high as number seven in late 1959, and “Baby Rocked Her Dolly” (#496), which made it to number fi fteen in 1960. That same year he won the

Cashbox

award for “Most Promising Country Artist”—

an irony, given that none of his subsequent recordings (on Starday, United Artists, and elsewhere) did as well as those fi rst Gold Star Studios–produced hits.

Among the many other notable Starday artists who recorded at Quinn’s place was Benny Barnes (1936–1987). His “Poor Man’s Riches” (#262) impressively soared to number two on the country charts in 1956. As Andrew Brown writes for the

Benny Barnes

compilation, “He had defi ed current trends and record industry wisdom by hitting with a hard country performance at a time when rock ’n’ roll had threatened to consume everything in its path.” The Beaumont native’s fi rst single for Starday had featured “Once Again” backed with “No Fault of Mine” (#236). But his second Starday release, “Poor Man’s Riches,” was the best-seller, and it was also reissued on Mercury (#71048). His last single for Starday, credited to Benny Barnes with the Echoes, was “You Gotta Pay” backed with “Heads You Win (Tails I Lose)” (#401). After that, like his friend George Jones, Barnes moved to Mercury. But he continued to be produced by Daily and, through 1959, make records at Gold Star Studios (for the Mercury, Dixie, and D labels).

Another Texas singer who came to Gold Star to record for Daily was Roger Miller (1936–1992), best known for later hits (such as “Dang Me” and “King of the Road”) recorded elsewhere for other labels. In 1956 Jones had introduced the unproven Miller to Daily, leading to the production of several singles, including two issued on Starday: “Can’t Stop Loving You” backed with “You’re Forgetting Me” (#356) and “Playboy” backed with “Poor Little John” (#718).

Other Daily-produced tracks by Miller were released on Mercury, including a reissue of “Poor Little John” with “My Pillow” (#71212). Quinn had engineered all of these.

The lineup of Gold Star staff musicians regularly used during its prime Starday era (1954 to 1957) included the following: Hal Harris, Eddie Eddings, Glenn Barber, or Cameron Hill on lead guitar; Ernie Hunter, Earl Caruthers, Joe “Red” Hayes, Kenneth “Little Red” Hayes, Tony Sepolio, or Clyde Brewer on fi ddle; Herb Remington, Frank Juricek, Al Petty, or Buddy Doyle on steel guitar; Charles “Doc” Lewis or “Shorty” Byron on piano; Russell “Hezzie” Bryant, Ray “Shang” Kennedy, or J. T. “Tiny” Smith on bass; and Bill Kimbrough, Red Novak, or Darrell Newsome on drums. As Glenn Barber says, “It was a real who’s who of Houston singers and musicians.” Frank Juricek adds, “We always had great guitar players on our sessions. Quite often it was Hal Harris.

5 8

h o u s e o f h i t s

Bradley_4319_BK.indd 58

1/26/10 1:12:13 PM

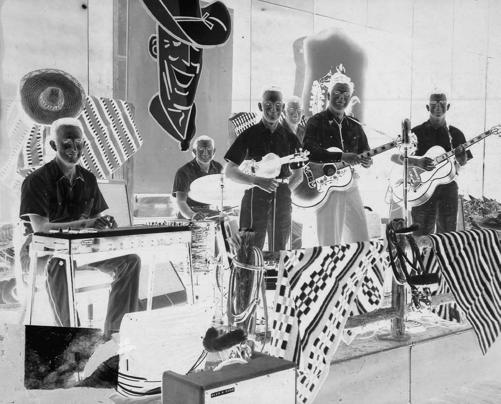

The Sun Downers (left to right, front row: Herb Remington, Clyde Brewer, Johnny Ragsdell, Frank Whiteside; back row: Red Novak on drums, Hezzie Bryant), at the Rice Hotel ballroom, Houston, 1950s

He started that plucking guitar stuff when it became the thing to do or the new sound in country records.”

As for Hal Harris (1920–1992), he was a highly respected fi nger-picking guitarist who played on numerous Gold Star sessions. His aggressive guitar style shone brilliantly on many country and rockabilly recordings for Starday or D Records, including some credited to Jones, as well as others by Barnes, Barber, the Big Bopper, Link Davis, Eddie Noack, Ray Campi, Bob Doss, Sleepy LaBeef, Rock Rogers, and others.

p a p py d a i ly a n d s t a r d ay r e c o r d s

5 9

Bradley_4319_BK.indd 59

1/26/10 1:12:13 PM

By documenting and publicizing artists such as these during the mid-1950s, Starday ranks right up there with Quinn’s previous Gold Star Records label in terms of historical signifi cance. They both were early, infl uential, and unusually prolifi c independent Texas-based companies recording regional talent. Their respective catalogues are now cultural artifacts, a rich source of mid-twentieth-century roots music from the state’s largest city.

As for Gold Star Studios, the numerous Daily-produced sessions there for Starday (and for its Mercury affi

liation) provided what was surely Quinn’s

most important source of income from 1955 through 1959. However, he was still recording a variety of performers for other labels during this period. (For instance, in 1956 eventual country star Mickey Gilley made his fi rst single there for Minor Records.) Yet the Quinn-Daily business relationship was crucial to the fi nancial stability, and subsequent expansion, of the Gold Star enterprise, and it would continue even after Daily left Starday.

6 0

h o u s e o f h i t s

Bradley_4319_BK.indd 60

1/26/10 1:12:13 PM

7

The Big Studio

Room Expansion

ust as the 1950s were a boom

time for certain local independent record companies such as Starday, even more so were they a period of explosive expansion and prosperity in Houston proper.

As Bob Allen writes, “All roads led to Houston in Southeast Texas in the early ’50s. The teeming port metropolis was growing so rapidly from the spoils of the cattle, oil, and shipping industries that it was practically bursting at the seams.” Given that context, perhaps it is not surprising that, even though scores of important records have been made there, Houston would rarely be considered a major recording center.

After all, Houston would never really develop or promote itself as such. By 1950 there was so much money being generated in the city’s many business arenas that civic leaders and power brokers likely scoff ed at the notion that recorded music could possibly be one of its prime exports. Perhaps unlike Nashville, the rapidly rising petrochemical capital of the nation did not really need the music business. At any rate, lacking any leadership or support from outside their decidedly eccentric ranks, the various studio proprietors, A&R

producers, label owners, and musical forces never coalesced to create a collective identity for, or to promote, the Houston recording scene.

Nonetheless, it was a fertile and profi table era for some of the shrewdest of the independent music producers. And none was sharper than the Starday Records cofounder known by the paternal nickname. As Allen goes on to say,

“If you came down the pike to Houston with music in your mind, the man to see was Harold W. ‘Pappy’ Daily . . . who had slowly built himself a small empire.” Just as the Duke-Peacock owner Don Robey, despite the presence of many competitors, dominated the local recording of black talent in the 1950s, Daily prevailed over much of the white music scene. Their business pursuits Bradley_4319_BK.indd 61

1/26/10 1:12:13 PM

surely stimulated the city’s job market for engineers, songwriters, and musicians, as well as other investments in real property, equipment, and related services. But though they built impressive companies, neither Daily nor Robey could ultimately transform the role of music recording in Houston’s overall economic development.

Nonetheless, for regular session players such as Clyde Brewer, the 1950s were a fi ne time to be working in the city. He says,

Herbie [Remington] and I would get a call almost daily from either Quinn [of Gold Star Studios] or Holford [of ACA Studios] to cut a serious session for a record company or a vanity record for anyone wanting to ride the coattails of George [Jones], Benny [Barnes], or [Big] Bopper.

As far as the founder of Gold Star Studios was concerned, in the late 1950s things were going pretty well. In fact, from late 1958 to early ’59, Quinn had constructed a large new recording studio of his own design. By expanding off the back and one side of his house (the ground fl oor of which remained a smaller studio), he had created a sizable and splendid sanctuary of sound.

Since the bulk of the new building spilled over into the previously vacant side yard, it got its own entrance and street address, 5626 Brock, while the house number remained 5628.

In addition to the big studio room, the fi rst fl oor of the new building also housed two bathrooms, an entrance foyer and reception offi

ce, the stairwell

to the control room, and an engineer’s offi

ce that led directly into the studio

area. The exterior looked like a corrugated steel Quonset hut. The dimensions ran forty-eight feet long by fi fty-three feet wide, with a ceiling height of twenty-two feet. The fl ooring was a type of hardwood parquet. The walls were covered with acoustic tiles and strategically placed heavy drapes that Quinn’s wife had made. There were two vocal booths situated in the back corners below the large window, which signifi ed the control room. In a highly unusual move, Quinn had installed the control room upstairs on the second-fl oor level, off ering it an overhead view of the performance space below.

That control room ran twenty feet wide by sixteen feet deep, with a ceiling height of ten feet. Its wall surfaces and ceiling were covered with acoustic tiles. The fl oor was carpeted to reduce some of the sonic “liveness” caused by the huge window. Considering where Quinn had placed the stairway in relation to the new studio, it was a walk of many steps from the fl oor where the musicians performed up to the control console. However, because of the studio’s unusually grand size, that elevated vantage point off ered exceptional sightlines for the engineer.

6 2

h o u s e o f h i t s

Bradley_4319_BK.indd 62

1/26/10 1:12:13 PM

Bill Quinn, at the gate to Gold Star Studios (with the “Big Room” expansion in the background), 1960 (photo by and courtesy of Chris Strachwitz) The mixing console consisted of several Ampex MX-10 tube mixers ganged together. The fi rst state-of-the-art machines that had been set up at Gold Star Studios in 1955 were Ampex 350 and 351 mono tape machines. The fi rst multitrack machine, installed in 1960, was a three-track Ampex machine. In the mid-1960s it would be upgraded to an Ampex four-track that recorded on half-inch tape. Mixing was done fi rst to a mono Ampex 350 quarter-inch machine and later in the mid-1960s to a quarter-inch Ampex 351 stereo machine.