Horsekeeping (19 page)

Authors: Roxanne Bok

In late September the rubble finally was cleared away. George reverted to living in his car for months, unwilling to give up on his damaged home, and felt compelled to stand guard against varmints and voyeurs. He posted too many KEEP OUT/NO TRESSPASSING signs, inviting attention. Because of a fall that broke her neck, Ursula spent time in hospital and then in a nursing home, the very fate she had feared. But she adamantly refused to move to Illinois with Ross, and, still in possession of her Yankee iron will, planned to rebuild. I hoped she would live long enough to see it through.

CHAPTER TEN

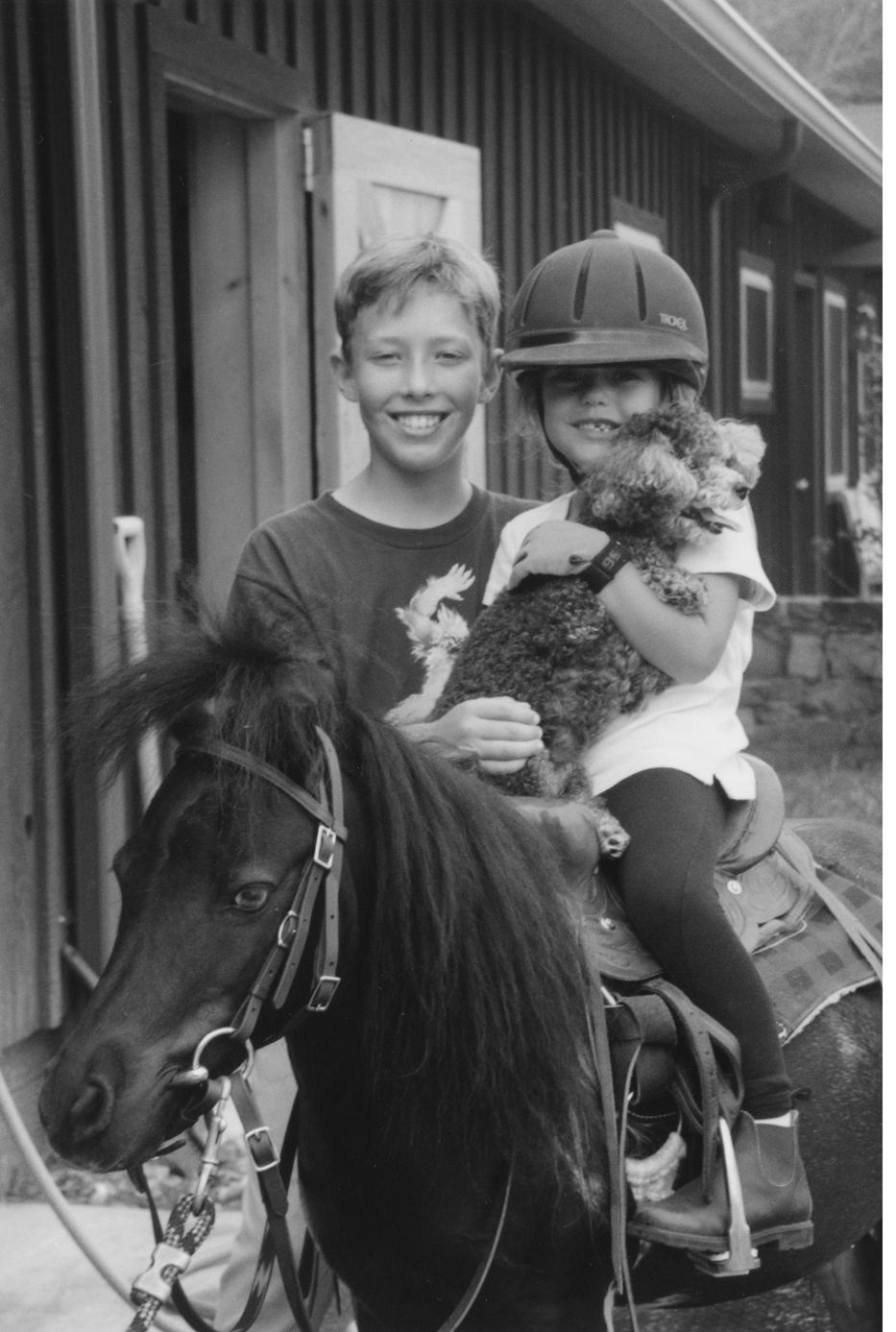

A Colt and a Filly

I

N ACCORDANCE WITH THE HYPERBOLIC PHRASE, I would “kill for” my children, Elliot and Jane, as they are my own flesh and blood. I fully believe I could lift a vehicle off my kid as described in those emergency tales of superhuman strength. When Jane asks how much I love her, I honestly submit a superlunary answer.

N ACCORDANCE WITH THE HYPERBOLIC PHRASE, I would “kill for” my children, Elliot and Jane, as they are my own flesh and blood. I fully believe I could lift a vehicle off my kid as described in those emergency tales of superhuman strength. When Jane asks how much I love her, I honestly submit a superlunary answer.

“I love you and Elliot more than anyone or anything in the entire universe.”

“Even more than Daddy and Velvet?” she asked.

“Yes, even more than the two of them put together.”

“Hey,” Scott said, “I'm sitting right here.”

“Someone I created takes precedence over someone I married.” I rolled my eyes at him like “

duh

.”

duh

.”

“Where do I rank against the pets?”

“Velvet or Bandi?” I frowned, thinking it over.

And I am not even especially maternal, not naturally the giving type. One by one our friends began spawning with gusto claiming that “your life isn't complete without kids; it's what

makes

a family.” Ambivalently, after fourteen years of marriage, we took the plunge, had one, barely made it through the baby stage and then, according to rules of genetic conspiracy, five years later we forgot the mastitis and sleepless months and had another, and persuaded everyone we knew to do the same to convince ourselves we had done the right thing. There is no u-turn, nor any upside in admitting that life as we had known itâlong Sunday mornings with the

New York Times

, sex without the door barricaded, some hours of the week with nothing to do, a leisurely, narcissistic self-indulgenceâceases to exist, and the needy, adorable little people, whom you love more than anyone you have ever known includingâand this is bigâ

yourself

, are yours for life. And though other parents do not like to admit it, and with rare exceptions, we really only deeply love our own: everyone else's just don't compare. It's primal.

makes

a family.” Ambivalently, after fourteen years of marriage, we took the plunge, had one, barely made it through the baby stage and then, according to rules of genetic conspiracy, five years later we forgot the mastitis and sleepless months and had another, and persuaded everyone we knew to do the same to convince ourselves we had done the right thing. There is no u-turn, nor any upside in admitting that life as we had known itâlong Sunday mornings with the

New York Times

, sex without the door barricaded, some hours of the week with nothing to do, a leisurely, narcissistic self-indulgenceâceases to exist, and the needy, adorable little people, whom you love more than anyone you have ever known includingâand this is bigâ

yourself

, are yours for life. And though other parents do not like to admit it, and with rare exceptions, we really only deeply love our own: everyone else's just don't compare. It's primal.

While Scott and I will do absolutely anything for them, it doesn't mean that self-sacrifice is returned. By nature, children experiment, and we are the laboratories. Just when we think we've got their fastball sorted out, they throw us a curve: Elliot yells “Damn it” in the middle of a crowded store when they are out of cupcakes; both kids get ornery and bored while sitting among enough toys and books to stock a day care center; Jane throws her first and only tantrum during an all-important elementary school interview (the bright-eyed admissions director turned sullen at my protestations of “that's a first, we've never seen that before,” and replied “Of course,” while scribbling Xs and !!!s across our file); one regresses and wets the bed again just when I had disposed of the waterproof mattress pad, and, well, you get the picture.

Scott and I are decent parents, maybe even better than average. But we have our weak spots. For Scott, it's the car. When both kids jabber at once to a tired Pa who just finished a hard week's work, trying to get his attentionâthat is, each trying to get all the attention, pitching the decibels louder and louder, and Scott is trying to maneuver a Suburban around the craters on the Willis Avenue bridge at rush hour, and 1010 WINS is blaring a twenty-minute backup on the Bruckner Boulevard onto which we have just turned, well, think pressure cooker and Linda Blair. I smile smugly when Scott loses it because it is so rare. Volatility is more my trademark with mealtimes, particularly family dinners, my Achilles heel. An example:

“Jane, please tell Elliot dinner is ready.”

Scott is already doing his best to tilt this dinner toward success. Flattering Jane with a job gives her some ownership and a vested interest in cooperation.

“OK, Daddy,” she chirps, and runs in tight, excited steps to the playroom.

“Aayot [her mutilation of Elliot], come eat dinner.”

Immediately she races back.

“He's not coming.”

“Yes I am, Jane, give me a minute. Sheesh,” Elliot yells, slamming his laptop shut.

He bounds in and slumps into his chair. We assemble around the table, and the kids assess their plates. Neither child is happy with the appetizing marinated chicken and broccoli that Scott has given up time with his Sunday newspapers to lovingly prepare. Tonight, like all nights, they would have preferred pasta with “Farmer John cheese” as Jane persists in calling parmesan. But, to his credit, Elliot rallies.

“Rub-a-dub-dub, thanks for the grub.”

Scott and I cautiously exchange glances. Our hopes rise. Maybe tonight will be that rare experience of cute word-play and meaningful conversation, where we manage to keep some control and perhaps impart a tiny bit of wisdom, so that even if we cannot quite label the meal pleasurable, we can tag it a “learning experience.”

“Mommy, when will I get booties?” Jane says, suddenly looking very concerned.

Elliot chokes, spits some chewed greens onto the lazy Susan and howls because he knows that Jane means “boobies,” her twice-mangled euphemism for breasts. She has been asking this question a lot lately, and Elliot, embarrassed about all things sexual, finds it hysterical every time. I'm just grateful when the “booties” question comes out at home rather than in an elevator, or in church. Maintaining an even keel, I reply:

“Elliot, don't be a barbarian. Please eat over your plate and use your fork. I've told you Janie, you'll grow breasts when you're a teenager, but only if you eat your dinner.”

“What's a teen-angle again?

“A teen

ager

is someone thirteen, fourteen, fifteen, sixteen, seventeen, eighteen, or nineteen years oldâall the numbers that end in âteen.' Please take a bite of chicken. Daddy made it special for you and it's really yummy.”

ager

is someone thirteen, fourteen, fifteen, sixteen, seventeen, eighteen, or nineteen years oldâall the numbers that end in âteen.' Please take a bite of chicken. Daddy made it special for you and it's really yummy.”

“What's for dessert?” Jane wants to know.

Elliot snorts again, sending milk out of his nose.

“EE WWW , GROSS,” Jane declares.

Dessert is a loaded topic. Because Scott and I have fallen into the trap of bribing Jane with dessert to prompt her to eat her dinner, a practice that the childcare gurus declare the ultimate no-no, it raises our hackles. Every day we say we have to call a halt to the practice, but there is usually some mitigating circumstance that saps our will. It doesn't help that Elliot eats well: rather, it makes us feel like we've run out of steam with child number two. Elliot takes great pride in his attention to vegetables and his restraint regarding dessert, if only as a way to distinguish himself from his little sister, who, as he has announced on numerous occasions, was “the worst thing that ever happened to me when I was five.” Internally, Scott and I are beating our selves up about our inadequate parenting in regard to food and projecting ahead to inevitable eating disorders, and then my thoughts shift to Cain and Abel, but little Freudian Jane has already moved on:

“Will I get a penis when I'm a teen-angel?”

Elliot bursts out: “Of course not, Janeâyou're a girl. You have a

vagina.

Sheesh!”

vagina.

Sheesh!”

“Sheesh!” Jane shouts louder, and rolls her eyes at her brother.

A volley of “sheeshes” ensues.

I consider myself lucky that body parts are only discussed. My good friend's daughter once showed her vagina to her grandfather at the dinner table.

Scott comes to the rescue with the double-whammy of a conversation stopper:

“HEY! Elliot. Tell me one good thing that happened in school today. Jane, eat a carrot.”

Dead silence, with the exception of scraping forks sculpting food pyramids.

That's inventive,

I think to my own unimaginative, sulking self.

I think to my own unimaginative, sulking self.

“Well?” Scott persists.

“Lunch and recess,” Elliot sullenly replies.

“That's two. Did you finish reading

Skinnybones

? Jane: pick up a carrot, put it in your mouth, chew it and swallow it or Daddy will be very angry with you.” He looks back at Elliot, who, feeling the pressure, replies,

Skinnybones

? Jane: pick up a carrot, put it in your mouth, chew it and swallow it or Daddy will be very angry with you.” He looks back at Elliot, who, feeling the pressure, replies,

“Of course I finished

Skinnybones

. It was so dumb.”

Skinnybones

. It was so dumb.”

Elliot re-slumps and probes a piece of chicken only to smear it around in a dollop of ketchup. Simultaneously, he rolls his eyes at no one and Scott rolls his eyes at me. Looking for support, he forces a smile, and I icily return a grimace. Mouth full of carrot, Jane pipes in:

“Daddy, you have a big butt.”

Elliot snorts out some more food, and Scott knows instinctively that this will push me over the edge into my “I hate eating with the kids mode,” about which we both know I will later suffer guilt because, as the same aforementioned child-rearing experts have said, it is crucial to their pint-sized psyches to share quality mealtimes. Right now, I would rather be having a root canal with some good nitrous. This thought sours me more, but I feel I should defend my maligned husband.

“Jane. That is not a nice thing to say. And Daddy does not have a âlarge bottom'. People come in all different shapes and sizes and it's what's inside that matters.”

The content of my saccharine speech falls as flat as my delivery. To quote a Dr. Seuss character: “I said and said and said these words, I said them but I lied them.”

Losing ground, I cave and pull out old faithful.

“Besides, Jane, you are not eating your dinner. Please eat a piece of chicken. When you eat well, you can have an Oreo for dessert.”

“I'm eating a carrot.” Jane opens her mouth wide to display chewed carrot, but it is not lost on any of us that though Jane has artfully rearranged her plate, she is still working on her first bite of the meal. The rest of us, meanwhile, have set a record pace in order to end our misery. Elliot, impatient for some Oreos, can't restrain himself any longer.

“Jane, you are so slow. And, you have the worst eating habits. All you ever eat is candy and ice cream and snack all day long. You're gonna' be fat.”

Jane crumbles. Shoulders sagging, she hangs her large head in shame. Her straight brown hair covers most of her face, and hot tears drip onto her untouched chicken.

“Good move, El,” I say.

“But it's true,” he protests, genuinely hurt.

“Jane has to learn to pace herself just like you did when you were four. Please say you're sorry to Jane, and Jane, please have a bite of chicken.” I catch her just before her “woe is me” point of no return.

There is a thoughtful pause in which we are all humbled. Elliot rescues us.

“Sorry, Janie.”

“It's okay, Aayot.”

Â

Â

I REALIZE THAT A KID BEHAVING BADLY IS EXPECTED and necessary for proper development. And it is often funny in retrospect. But there are the times when parents behave atrociously and can broker no excuse. Many of us have cringe-worthy experiences we wish we could take back or at least forget. They never invoke nostalgia and torture us forever. My lack of skill on one particular day shocks me still.

I had had too much tea, caffeine being both necessary and the enemy. On the one hand, I'm naturally tightly wound, and stimulants are the last thing I need. On the other, to play with my kids on weekend mornings instead of sleeping late while they watch videos, I need a little boost.

So, this Saturday morning in February, in Salisbury the cruelest month, I was over-caffeinated and bushed from a long week.

So, this Saturday morning in February, in Salisbury the cruelest month, I was over-caffeinated and bushed from a long week.

Other books

The Rogue Crew by Brian Jacques

ALWAYS FAITHFUL by Isabella

Crossroad Blues (The Nick Travers Novels) by Atkins, Ace

Sarah Gabriel by Keeping Kate

Snakeskin Shamisen by Naomi Hirahara

Night of the Living Dummy by R. L. Stine

Plunder of Gor by Norman, John;

Ryan by Vanessa Devereaux

The Rise & Fall of Great Powers by Tom Rachman

Babylon by Camilla Ceder