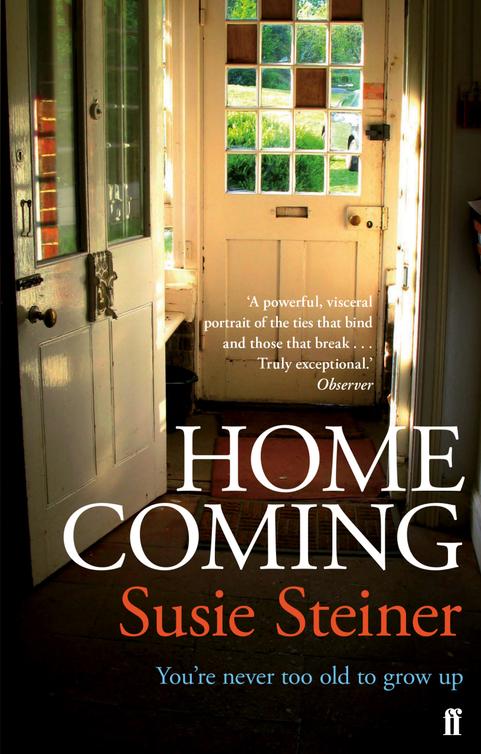

Homecoming

Authors: Susie Steiner

Susie Steiner

For Tom

— The start of the farming year —

Joe closes his back door, his feet cold inside his boots as he steps out into the yard in the dark. He can smell the rain coming and digs into his pocket for his phone.

‘Yep?’ says Max.

‘Let’s lift this beet then, shall we?’

‘I thought I was sorting it,’ says Max.

‘So did I. Ted Wilson brought a machine over last night.’

‘I was going to call him,’ Max says.

Joe listens to the fat cooing of a wood-pigeon somewhere over by the hay barn.

‘I were waiting for a break in the wet,’ Max says.

‘Well, you’d have a long wait then, wouldn’t ye? I’ve done it now.’

‘It’s set to tip it down,’ says Max.

That boy. Always looking for the obstacles.

‘We’ll just have to do best we can,’ says Joe, careful of his tone. ‘How soon can you get down here? You’ll need to hitch the trailer to the John Deere. I’ll meet you over on the in-bye.’

He pulls himself up into the harvester’s cab. The brown seat is frayed and sagging and he can taste the age on her: a diesel leak, worn metal. The dust off other farmers’ boots. First time he’s not been able to afford Wilson’s lads to lift the fodder beet for him, and here he is, pushing sixty, trying to drive a clapped-out harvester he’s never set eyes on before.

Joe starts the engine and pushes his foot gently down on the gas, feeling for its bite, keeping his eyes on the rear-view mirrors which are big as tea trays. Then he’s easing the harvester out through the farmyard gate with his mouth hanging open from the concentration of it; turning at a stately crawl, sharp right past his own front door.

Ann’ll be waking.

‘Shouldn’t you be lifting the beet?’ she’d said, more than two weeks ago. But the rains had never ceased, the ground as sticky as a clay-pit. So they’d waited. And she’d been on at him, too, about the money – how much he’d have to get at Slingsby to make the next rent payment to the water board and whether the stores would fetch more than fifteen pound a lamb this year. She wanted out. He knew she did. Wanted ‘a retirement’, she said, that wasn’t all watching the weather and getting up at dawn. She was pressing him to hand over more to Max, so he’d said it was Max’s job to sort the beet. And then he’d watched him as the days passed and it didn’t get done.

He’s gaining the feel of the harvester now: her weight against the gas. Marpleton village green slides by to his left and he glances across it at his slow roll: sees the Fox and Feathers unlit, and beyond, in the lightening dawn, Eric and Lauren Blakely’s house – a former rectory which stands taller than the workers’ cottages around it. Eric with his indoor shoes and his Nissan Micra, his farming days behind him. Alright for them, they’d owned their land. They weren’t tenants like him and Ann. All that work – farming a hundred acres, tending five hundred Swaledales on the moor, and what would they have to show for it? They were worth less every month, even with all the love and care that went into them and the patience they gave back, standing out on the moor in the harshest winters. No, they couldn’t be left. Max wasn’t ready.

Joe pulls off the road onto a dirt track that crosses the in-bye and feels the comfort of looking out across the lowland where his forage crops are grown and grass for hay and silage; fields penned by dry stone walls, where rams are put to the ewes at tupping and where the lambs are born. He marvels that he’s grown to love it so – when it was a thing foisted on him, not chosen. And who’d keep this in order if he were gone? Handing it on to Max – well, look how that was going. Couldn’t even organise for the beet to get lifted.

The sky is thundery and low as he pulls up beside a wall and jumps down from the cab. He looks across the field at the green tops of the fodder beet stretching away. The ground giving up its treasure to him: it was a beautiful thing. He pictures the soil and the layers – the substrata – brown then red, then glaring orange, reaching down to the earth’s core where it was hot. And him on the surface, gathering its riches up – drilling goodness and filtering it into trucks. This was what a man was meant for. What did she want him to do, if not this?

*

Max presses the red button on his phone. He’s standing next to his Land Rover in the yard outside his farmhouse, not five miles from his father’s. He can feel the energy drain out of him. Joe had only said a week ago – about lifting the beet – and already he’s fallen short. Maybe he could’ve got round to it sooner, but he was caught. Never knew how much to spend or which was the right way. If he’d scrimped, Joe would say he should’ve been bolder. If he’d paid full whack and got in Ted Wilson’s boys, Joe would’ve asked him if he thought they were made of money. So he’d put it off, waiting for a break in the wet and to see if the answer might come to him.

He gazes at the farmhouse where a light is coming on. It casts a weak glow over the yard and the front door opens. Primrose is standing in her nightgown with her wellingtons on. Her nightie is see-through and her thighs are silhouetted in the yellow of the hall. ‘Sturdy,’ Joe had said of Primrose, when they announced they were to marry, and Max wasn’t sure if this was a compliment or another gibe.

‘Going over to the in-bye,’ he shouts to her across the yard. ‘Lifting the beet.’

‘In’t it too wet?’

‘Aye, well. He’s hired a machine off Ted Wilson, ha’n’t he. So it’s got to be today.’

‘Right,’ she says. ‘I thought you were s’posed to be sorting it.’

‘Doesn’t matter who sorts it, does it?’ he says, turning away from her and opening the car door. ‘S’long as it gets done.’

*

She walks into the kitchen. The lights are on and their claustrophobic glow creates a feeling of night abutting wakefulness. She puts a kettle on to boil and hears a thunder-clap outside but no rain. The air is charged with electricity, warm with it. She prepares her tea and toast with the same ritual she follows every morning.

Primrose opens her DIY manual on the kitchen table and hunches over it, her tea in one hand, her toast in the other and the metal overhead light casting a cone from above.Within minutes she’s lost in a labyrinthine task involving earth terminals and flex and circuit-breakers. She examines a diagram of a ceiling rose, following, with dogged precision, the pathways of each wire and their connectivity: the ones that must be broken, the ones that must not be touched. ‘

Loosen the two or three terminals that hold the flex wires

,’ she reads. ‘

Remove the wires, taking care not to disturb any of the wires entering the rose from the circuit cable

.’ She stifles a yawn and is surprised at how hard it is to stay awake this morning. It isn’t like her, Primrose being one of those people who accepts being awake as an indisputable fact.

Ten minutes later she is easing flesh-coloured bra cups over her breasts. She flinches and rounds her shoulders. They are too tender, like when she’s on the blob. Her belly has the same over-ripe feeling. She looks in the mirror but she looks the same. She finishes dressing and washes her face with a cracked bar of Imperial Leather soap.

Out in the yard, she creaks and rustles in her anorak as she mounts her bicycle. The light is dusk-like under the lowered cloud and on the journey, the rain starts to plop in fat drops onto her shoulders. By the time she reaches the Co-op in Lipton two miles away, she is soaked through.

She’s first in. She unlocks the door and turns on the lights. They flicker on with a plink-plink, so that she sees flashes of the empty green plastic boxes for veg and the aisles of jams and tins and Mr Kipling cakes that last in their boxes for years.

She’s just taken her place on the high stool out front, with the

cigarettes

behind her – has lifted the stiff cover off the till, folded it and stowed it under her feet – when Tracy and Claire clatter in through the door in mid-conversation.

‘So what did she say?’ Tracy is asking Claire as they make their way past the till.

‘Hiya Prim,’ says Claire, smiling at her.

Primrose smiles back but doesn’t reply. There is a metallic taste in her mouth.

‘Come on,’ she hears Tracy saying at Claire’s back as they walk down to the staff room, past the mulligatawny soup. ‘I won’t say owt.’

She can’t hear Claire’s reply.

Primrose shifts on her high stool. She slouches, then straightens. She puts a hand on her lower belly.

*

Ann’s fingernails are painted with pink pearlised varnish which flashes and sparkles under the gloom of her umbrella as she hurries up Lipton High Street. Perhaps she shouldn’t have sent that email to Bartholomew. Toned it down a bit. ‘Your dad’s lifting the beet by himself – hired some rust bucket off Ted Wilson. Oh I do feel sorry for him, doing a job like that at his age, but he won’t stop. Won’t slow down. You’d think Max would step up.’

Her expression beneath the shadow of her umbrella is crumpled. She’s prodding her youngest for his usual response. ‘Sell up, mum. It’s too much of a strain at your age.’ And then she can argue against him, as if it’s some internal refrain she’s wanting to play out. ‘Sell what? Lamb prices are on the floor, house prices going up every week. We’d have nowhere to live.’

She wears a beige mac, darkened by the wet at her elbows and at the base of her back. Hanging from the crook of her bent arm is her handbag, large and practical. She is stooping, her feet taking quick steps on the pavement. They’ll be having a right job getting the beet up in this, she thinks. Joe’s been glued to the weather reports these last weeks – standing beside the kitchen radio, craning his ear, looking at his shoes. You were so at the mercy of the weather, farming. Like some poor referee between a low sky and the sodden earth. But Joe, he’d tell the clouds where to blow if he could.

The rain subsides, as if some hand has turned a celestial dial round to ‘off’. Ann slows her pace and stops outside Richardson & Smith, Residential & Farm property sales. Her umbrella and mac are reflected in the glass. Hovering just above her indistinct shoulders is a square panel containing four pictures: a farmhouse, some outbuildings, fields and a line map of the land. Frank and Joan Motherwell’s farm. She’d heard they were selling: millions, that land would go for. Cashing in on the bull market and moving abroad to start over. Somewhere hot, Maureen Pettiford had said yesterday, as Ann handed her coins across the counter in return for

The Times

.

‘Joan can’t wait to see the back of the place.’

‘And Frank?’ Ann had said.

‘He’s not taking it so well.’

Somewhere hot. She’d made Joe go on a holiday once. Long time ago, when money wasn’t so tight. Never again. The fidgeting. The deep sighs, then heaving himself off the lounger to call Max.

She’d said to him, only last week, ‘Max managed alright then, didn’t he? When we went to Málaga that time?’

‘If doing nowt is managing,’ Joe had said.

‘Oh come off it,’ she’d said, but he’d shot her a look, like she was trespassing where she shouldn’t.

‘Slowly, slowly catchy monkey,’ Lauren had counselled, when she’d gone across the green for a cup of tea.

Ann begins to feel the wetness that has slid off her umbrella; a cool patch at the base of her spine. She is taking in the sunflower-yellow colour on Joan Motherwell’s kitchen walls and the patterned blue curtains which look like a toddler’s defaced them. She grimaces. Her own house wouldn’t come off much better, mind. Bet Joan can’t believe her luck. She thinks of the desultory yard at home, a mess of machinery parts and ripped hessian sacks; the pole barn for hay and straw, clumps of it strewn into the mud.

‘That’s a fair old price is that,’ says a familiar voice at her shoulder. Ann spins round. It is Lauren, her face smiling out from beneath a giant floral umbrella. ‘Makes Eric and me wonder if we shouldn’t have held on for a bit longer. Market seems to go up every week.’

Ann nods. She pats her collar-bones. They both peer at the Motherwell farm details.

‘I know they’ve had to struggle,’ says Ann, ‘what Joan’s been through, tearing Frank away from the place, but still, that’d take the edge off.’

‘She still has to live with Frank,’ says Lauren. ‘Frank without a farm. Wouldn’t wish that on me worst enemy.’

Easy for Lauren to say. Ann and Joe, they’d be lucky to get enough for a two-bed flat on the trunk road out of Malton. Above the Chinese. Perhaps it was better to press on, like Joe said: stay in the big house where her bairns were born. Wait for things to get better.

Lauren is rubbing her shoulder. ‘Don’t think on,’ she says. ‘There’s nothing you can do about it so don’t think on. Lamb prices’ll pick up. Here, do you fancy darts tonight – at the George in Morpeth-le-Dale? It’s just a friendly – they haven’t chosen the league yet, but between you and me, I think the captaincy’s in the bag.’

‘I don’t know,’ says Ann, patting her collar-bones again. ‘I don’t know the rules.’

‘Don’t be daft. I can fill you in. I’ll pick you up at seven.’

‘Alright then, yes. I’d love a lift.’

‘Get that wrist action going,’ says her friend as she walks backwards away from Ann, her hand nodding with an imaginary dart, her face drenched in red from her umbrella.

Lauren has, over twenty years of friendship, taught Ann the value of hobbies – ladies’ darts, the WI, flower-arranging, church committees, life-drawing classes – and Ann is continually surprised by the richness these diversions bring to her life. On the face of it, they provide contact with others which Ann, well, she’d be shy about it normally. More than that, they bring her a singular involvement in the moment: herself, up against all these new things, even if it was only poking a delphinium into a damp block of oasis. Often she showed no discernible talent – her pottery was shocking. But as she got older this seemed to matter less. The vanity of youth – what a liberation it was to be free of it. It is age, too, that’s taught her a kind of dogged tenacity. She’s realised, late in the day, that the stringing together of small things, and keeping going – above all plodding on – is what makes a life.

Nevertheless, she has to fight resistance at her core – her inner sod – which pours scorn on her hobbies and plays on her desire to stay cocooned at home, instead of grimacing at the cold night like a physical shock and some draughty hall full of strangers, or worse, acquaintances, to whom she must present herself, jollied up with a sweep of Yardley lipstick. She dreads the navigating of the difficult few among the genial whole: those women who were barbed or envious or who presented to her a perfect life. Lauren didn’t seem to suffer the same reluctance, though age had also taught Ann that you never really knew how hard people were paddling beneath the surface.