Hollow Earth: The Long and Curious History of Imagining Strange Lands, Fantastical Creatures, Advanced Civilizatio (8 page)

Authors: David Standish

Tags: #Gnostic Dementia, #Mythology, #Alternative History, #v.5, #Literary Studies, #Amazon.com, #Retail

BOOK: Hollow Earth: The Long and Curious History of Imagining Strange Lands, Fantastical Creatures, Advanced Civilizatio

12.48Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

The next round of northern exploration commenced within a few years of Columbus’s epochal (if mistaken) voyage of 1492. As is well known, he was aiming for Cathay, the spices and other profitable exotica of the Orient. Instead he slammed into a New World quite inconveniently in the way. Dreaming of a passage to India, when he reached Cuba he was convinced it was mainland China and sent a full dress party that included an authorized representative of the pope into the interior expecting to find some grand city, and of course he insisted on calling the inhabitants Indians. This was the first attempt in an ultimately futile search that would last another 350 years for that tantalizing shortcut to Asia.

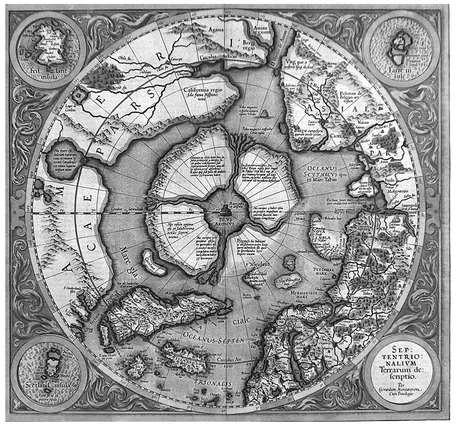

The idea of an open polar sea got a boost when Gerardus Mercator’s revolutionary—and beautiful—world map appeared in 1569. It rendered the earthly sphere into rectangular grids for easier use by navigators, even though the proportions got pretty weird in the north and south, with Greenland looming like Godzilla over puny North America cringing beneath it, one-tenth its size. Showing the arctic regions according to this scheme proved impossible, so Mercator drew another map of the Arctic, from a point of view in outer space above the planet. He combined several traditional elements—including an open polar sea—primarily drawing on a fourteenth-century text, now lost, called

The Travels of Jacobus Cnoyen of Bois le Duc.

It contained a summary account of travels to the north by an English friar who had gone there for King Edward III and written a book about it,

Inventio Fortunatae

, also now lost. But Mercator read Cnoyen’s book, and wrote a long letter about it to John Dee, Queen Elizabeth’s astrologer, in which he says the friar, using “magical arts,” claimed to have seen this utmost northerly place in 1360. The friar said that four arms of the sea rushed as torrential rivers between Arctic landmasses to form an ocean at the top of the world. These rivers crashed together at the pole, forming a terrible maelstrom that plunged into an abyss, the foaming water sucked down into the center of the earth. And so Mercator drew it in his polar map. Mercator places as his centerpiece at the pole a dark craggy rock—the legendary

Rupes Nigra

or Black Precipice, the lodestone mountain toward which all compasses presumably pointed.

12

The projection suggests a broken donut, with an inner sea as the hole and plenty of ocean space for navigation between the four northern landmasses and the known continents to the south. Thus his map of polar regions inadvertently served as an advertising poster for the open polar sea and a shortcut to Asia—and one that Symmes certainly knew.

The Travels of Jacobus Cnoyen of Bois le Duc.

It contained a summary account of travels to the north by an English friar who had gone there for King Edward III and written a book about it,

Inventio Fortunatae

, also now lost. But Mercator read Cnoyen’s book, and wrote a long letter about it to John Dee, Queen Elizabeth’s astrologer, in which he says the friar, using “magical arts,” claimed to have seen this utmost northerly place in 1360. The friar said that four arms of the sea rushed as torrential rivers between Arctic landmasses to form an ocean at the top of the world. These rivers crashed together at the pole, forming a terrible maelstrom that plunged into an abyss, the foaming water sucked down into the center of the earth. And so Mercator drew it in his polar map. Mercator places as his centerpiece at the pole a dark craggy rock—the legendary

Rupes Nigra

or Black Precipice, the lodestone mountain toward which all compasses presumably pointed.

12

The projection suggests a broken donut, with an inner sea as the hole and plenty of ocean space for navigation between the four northern landmasses and the known continents to the south. Thus his map of polar regions inadvertently served as an advertising poster for the open polar sea and a shortcut to Asia—and one that Symmes certainly knew.

Symmes insisted on this open sea for his own purposes, of course. It was additional “proof” of his polar openings and the idyllic interior that beckoned. But Symmes’ polar dreams were in the mainstream zeitgeist. True, he took his polar fascination one toke over the line, but it was going around. A polar mania in the form of voyages of exploration, both north and south, reasserted itself after 1815 and was going full tilt when Symmes offered his theory to the world and himself as the leader of an arctic expedition. Symmes and his polar holes influenced thinking about the hollow earth from then on. After Symmes, ideas about the hollow earth, in real life and in fiction, become inextricably linked with the poles and polar exploration, right down to the present.

Finding a shortcut to Asia from Europe through a Northwest Passage had initially appealed to the English because the known routes to the Orient—around Africa and South America—had been monopolized by the Spanish and Portuguese. Over time the monopoly crumbled, but dreams of finding the passage lived on. The pursuit of it took on a certain frenzy during Symmes’ lifetime and must have contributed to his polar visions. Many of the polar “authorities” Symmes invokes in support of his theory were involved in seeking this icy grail.

Polar projection from Gerardus Mercator’s revolutionary world map. (Collection of The Map House of London)

The archipelago lying above the North American continent proved both tantalizing and maddening to these explorers. Around every cape might lie an open sea and a straight shot to Asia—or more bays that finally gave way to a shoreline, more large islands to navigate around, or a wall of ice. But great rewards lay at the end of the labyrinth if it could be found. The names of those who tried and failed ornament the map of northern Canada, a cartographical necropolis of brave futility. They include John Cabot, Jacques Cartier, Henry Hudson, and James Baffin.

Samuel Hearne, a Hudson’s Bay Company employee who made several heroic treks through the Canadian north between 1769 and 1772, became the first European to walk overland from Hudson’s Bay to the Arctic Ocean—and back!—thereby establishing that there was no sea passage through continental North America. His 1795 account of his adventures,

Journey from Prince of Wales Fort in Hudson’s Bay to the Northern Ocean,

makes stirring reading even today, and is cited repeatedly by James McBride in support of Symmes’ theory, particularly in regard to the abundance of wildlife Hearne encountered, taken as testimony of a mild interior where these creatures presumably overwintered.

13

Journey from Prince of Wales Fort in Hudson’s Bay to the Northern Ocean,

makes stirring reading even today, and is cited repeatedly by James McBride in support of Symmes’ theory, particularly in regard to the abundance of wildlife Hearne encountered, taken as testimony of a mild interior where these creatures presumably overwintered.

13

Noted naturalist Daines Barrington published

The Possibility of Approaching the North Pole Asserted

in 1775. It was reprinted with new material in 1818, the same year Symmes produced his first circular, and is another of the polar authorities McBride quotes in support of Symmes.

14

The Possibility of Approaching the North Pole Asserted

in 1775. It was reprinted with new material in 1818, the same year Symmes produced his first circular, and is another of the polar authorities McBride quotes in support of Symmes.

14

In 1789 Alexander Mackenzie, working for the North West Company, rival to the Hudson’s Bay Company, made an epic hike comparable to Hearne’s nearly twenty years earlier, from Lake Athabaska in present northeastern Alberta, to Great Slave Lake, where he encountered the beginnings of the river now bearing his name, following it over five hundred miles northwest to its mouth in the Beaufort Sea, above the Arctic Circle. In 1793 he crossed the Canadian Rockies and reached the Pacific; both journeys provided further verification that no continental passage existed. His

Voyage from Montreal on the River St. Lawrence, Through the Continent of North America, to the Frozen and Pacific Oceans, in the Years 1789 and 1793

was published in 1801, yet another resource McBride picked over in defending Symmes.

15

Voyage from Montreal on the River St. Lawrence, Through the Continent of North America, to the Frozen and Pacific Oceans, in the Years 1789 and 1793

was published in 1801, yet another resource McBride picked over in defending Symmes.

15

Exploration of the far north had almost died out in the early nineteenth century—until about the same time Symmes published Circular 1. Oddly, renewed interest in the Arctic resulted from the end of the Napoleonic Wars and the January 1815 Treaty of Ghent, which concluded the American–British War of 1812. In fighting these wars on almost worldwide fronts, the British had built up a huge naval fleet with hundreds of ships and thousands of sailors. Suddenly they had no one to fight. The result was massive layoffs (just as Symmes had been mustered out shortly after war’s end), officers reduced to half pay, and a splendid fleet lying idle. What to do with all those ships and well-trained officers? Second Secretary of the Admiralty John Barrow had a plan to keep at least some of them busy. Arguing that unlocking the secrets of the north had virtually become a matter of British honor, Barrow set several expeditions in motion that began a renewed effort that ended in 1854 with the first successful navigation of the Northwest Passage, 350 years after the first attempts. However, the route was so far north that it was useless commercially. Barrow, also a founder of the Royal Geographic Society, proselytized for and hyped this ambitious enterprise. In 1818 his

A chronological history of voyages into the Arctic regions; undertaken chiefly for the purpose of discovering a north-east, north-west, or polar passage between the Atlantic and Pacific: from the earliest periods of Scandinavian navigation, to the departure of the recent expeditions

appeared and sold rapidly.

A chronological history of voyages into the Arctic regions; undertaken chiefly for the purpose of discovering a north-east, north-west, or polar passage between the Atlantic and Pacific: from the earliest periods of Scandinavian navigation, to the departure of the recent expeditions

appeared and sold rapidly.

Four Royal Navy ships left England in April 1818—the same month Symmes began handing out his circular, offering to lead his own polar expedition—two in search of the Northwest Passage and two in an effort to reach the pole. Commander David Buchan headed the polar voyage, which was a complete bust. North of Spitsbergen they ran into horrific winds and wall-to-wall pack ice. They were back in London drinking hot toddies by October. The other expedition, led by Captain John Ross and Lieutenant William Parry, made some headway, though the explorers turned around for home due to what proved to be a major delusion on Ross’s part. The well-outfitted ships reached the west coast of Greenland by June, rediscovering Baffin Bay and naming Melville Bay just south of Thule. In early August, in far northwestern Greenland, they came upon a small band of Inuits, who were moved and amazed at these majestic creatures—the ships, which the Inuits were convinced must be alive. Awestruck, curious, they approached and addressed the ships, asking them, “Who are you? Where do you come from? Is it from the sun or the moon?” A crew member who spoke their language tried to explain. “They are houses made of wood.” The Inuit refused to believe him, saying, “No, they are alive, we have seen them move their wings.”

16

It is the most touching passage in all the arctic annals.

16

It is the most touching passage in all the arctic annals.

These were just the beginning of a succession of voyages mounted by the Royal Navy for the next three decades. Symmes must have ground his teeth in frustration at being left out of all this arctic exploration, to be on the sidelines watching. He was in many ways simply a product of the times, as things polar had captured the popular imagination. Eleanor Ann Porden, on meeting John Franklin aboard his ship just before his first voyage, was moved to lyrical ecstasies, publishing

The Arctic Expeditions: A Poem

in 1818. So moved, in fact, that on his return, she married him. In Scotland, a billboard-sized panorama—those scenic paintings on a roll that were slowly unspooled in theaters to music and commentary, a low-tech precursor to the movies—called

The Arctic

was playing to a packed house in Glasgow, described as

Messrs. Marshall’s grand peristrephic panorama of the polar regions, which displays the north coast of Spitzbergen, Baffin’s Bay, Arctic Highlands, &c. : now exhibiting in the large new circular wooden building, George’s Square, Glasgow: painted from drawings taken by Lieut. Beechey, who accompanied the polar expedition in 1818; and Messrs. Ross and Saccheuse, who accompanied the expedition to discover a northwest passage.

Journals and memoirs by arctic explorers became a growth industry in Symmes’ lifetime, and they must have rankled. What to do? Try even harder to get Symmes’ lifetime, and they must have rankled. What to do? Try even harder to get that expedition going.

The Arctic Expeditions: A Poem

in 1818. So moved, in fact, that on his return, she married him. In Scotland, a billboard-sized panorama—those scenic paintings on a roll that were slowly unspooled in theaters to music and commentary, a low-tech precursor to the movies—called

The Arctic

was playing to a packed house in Glasgow, described as

Messrs. Marshall’s grand peristrephic panorama of the polar regions, which displays the north coast of Spitzbergen, Baffin’s Bay, Arctic Highlands, &c. : now exhibiting in the large new circular wooden building, George’s Square, Glasgow: painted from drawings taken by Lieut. Beechey, who accompanied the polar expedition in 1818; and Messrs. Ross and Saccheuse, who accompanied the expedition to discover a northwest passage.

Journals and memoirs by arctic explorers became a growth industry in Symmes’ lifetime, and they must have rankled. What to do? Try even harder to get Symmes’ lifetime, and they must have rankled. What to do? Try even harder to get that expedition going.

Symmes left St. Louis in 1819. The country was experiencing its first serious economic depression, remembered as the Panic of 1819, a postwar slump compounded by a flaky unregulated banking system and greatly reduced foreign commerce. He gave up on Indian trading and moved his family to Newport, Kentucky, just across the Ohio River from Cincinnati. There is no information about what he did for a living there during the two years before he hit the lecture trail, how he supported that crowd of children. McBride says that he completely occupied himself with working out his theory.

He had already gained a bit of a reputation. Some zealous heartland boosters, eager to claim the frontier contained more than yahoos and grifters, had taken to calling him “Newton of the West.” He could be found some days at the new Western Museum in Cincinnati, hanging out with other esteemed scientists including John James Audubon, who worked there briefly and made a sketch of Symmes in 1820 for

Western Magazine

. In it he sits sideways at a table salted with several scientific instruments and a journal, a few fat volumes on a shelf, and a large globe with the North Pole cut off behind him. He wears a dark frock coat and a lighter collared vest, collar up, his thinning black hair combed forward to combat a deeply receding hairline, nose a little pointy, eyes a little squinty, brows beetley, mouth a little soft. He radiates a certain innocence and otherworldliness. Symmes shared Audubon’s interest in birds. He wrote a note for the

National Intelligencer

in 1820 about purple martins, largest of the American swallows, whose nests were everywhere in Cincinnati, so they clearly “delight in the society of man,” but they “migrate in a peculiar manner. It appears to be unknown from whence they come, and whither they go.” His speculation was that they migrated to somewhere else that people congregated.

17

Naturally he had a plan to find out—by banding them.

Western Magazine

. In it he sits sideways at a table salted with several scientific instruments and a journal, a few fat volumes on a shelf, and a large globe with the North Pole cut off behind him. He wears a dark frock coat and a lighter collared vest, collar up, his thinning black hair combed forward to combat a deeply receding hairline, nose a little pointy, eyes a little squinty, brows beetley, mouth a little soft. He radiates a certain innocence and otherworldliness. Symmes shared Audubon’s interest in birds. He wrote a note for the

National Intelligencer

in 1820 about purple martins, largest of the American swallows, whose nests were everywhere in Cincinnati, so they clearly “delight in the society of man,” but they “migrate in a peculiar manner. It appears to be unknown from whence they come, and whither they go.” His speculation was that they migrated to somewhere else that people congregated.

17

Naturally he had a plan to find out—by banding them.

Birds had been banded for centuries. A falcon of French King Henry IV’s is the first on record, lost in 1595, turning up a day later in Malta, 1,350 miles away. Audubon had been the first in America to do so, tying silver cords to the legs of fledgling phoebes in Philadelphia in 1803 and identifying a few when they returned the next year. Symmes gave specifics about these martin bands: they should contain the date and “a rough drawing of a ship, with the national flag, and drawings of some of the animals of the climate, as a sort of universal language; also, a request for the reader to attach a similar label about the time of the return of the birds in the spring, and to publish the circumstance in a newspaper of the country. If we do not by such means learn, soon or late, where the martins go, it will be inferable that they go to some unlettered people or unknown country.” Sly old Symmes. What unknown country and what unlettered people? He adds, “The more reasons we find for presuming there are unknown countries, the more we will be disposed to exert ourselves in research.” Even sitting on the porch of the Western Museum, idly musing on where martins go in winter, his thoughts turned ever back to the hollow earth.

Other books

The Anatomy of Violence by Charles Runyon

All Unquiet Things by Anna Jarzab

Chantress Alchemy by Amy Butler Greenfield

Dragon Magic by Andre Norton

Land of seven rivers: History of India's Geography by Sanyal, Sanjeev

Twilight by Brendan DuBois

The Dark: A Collection (Point Horror) by Cargill, Linda

Murder Path (Fallen Angels Book 3) by Max Hardy

Chasing the Lost by Bob Mayer

Educated by Tara Westover