Hollow Earth: The Long and Curious History of Imagining Strange Lands, Fantastical Creatures, Advanced Civilizatio (39 page)

Authors: David Standish

Tags: #Gnostic Dementia, #Mythology, #Alternative History, #v.5, #Literary Studies, #Amazon.com, #Retail

BOOK: Hollow Earth: The Long and Curious History of Imagining Strange Lands, Fantastical Creatures, Advanced Civilizatio

5Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

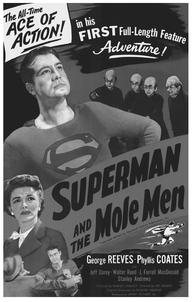

The hollow earth also figured as a motif in the first Superman feature film,

Superman and the Mole Men,

which hit theater screens in 1951 with the tagline, “The All-Time ACE OF ACTION! in his FIRST Full-Length Feature Adventure!” The movie starred television Superman George Reeves in his trademark outfit that looked like flannel pajamas with sewed-on decals and cape, with Phyllis Coates as Lois Lane. A yawner by today’s standards, the story has Clark and Lois out in Silsby, somewhere in the generic far Midwest, where a local oil company is completing the drilling of the world’s deepest well—which cuts into an underground realm inhabited by tiny radioactive “Mole Men,” two of whom decide to come up to the surface for a look around, causing, of course, widespread panic up top. They’re harmless, just pretty funny-looking, but the racist lynch-happy locals want to string them up anyway, and nearly do so before Superman steps in and makes peace. This epic was

so

low-budget that Superman isn’t even seen flying in it once (there are a few “Look! Up in the sky!” moments, but we never see what they’re looking at), but it did well at the box office, and was even recycled on the television show as a two-parter titled “The Unknown People.”

Superman and the Mole Men,

which hit theater screens in 1951 with the tagline, “The All-Time ACE OF ACTION! in his FIRST Full-Length Feature Adventure!” The movie starred television Superman George Reeves in his trademark outfit that looked like flannel pajamas with sewed-on decals and cape, with Phyllis Coates as Lois Lane. A yawner by today’s standards, the story has Clark and Lois out in Silsby, somewhere in the generic far Midwest, where a local oil company is completing the drilling of the world’s deepest well—which cuts into an underground realm inhabited by tiny radioactive “Mole Men,” two of whom decide to come up to the surface for a look around, causing, of course, widespread panic up top. They’re harmless, just pretty funny-looking, but the racist lynch-happy locals want to string them up anyway, and nearly do so before Superman steps in and makes peace. This epic was

so

low-budget that Superman isn’t even seen flying in it once (there are a few “Look! Up in the sky!” moments, but we never see what they’re looking at), but it did well at the box office, and was even recycled on the television show as a two-parter titled “The Unknown People.”

Look! Up on the screen! It’s the first Superman movie,

Superman and the Mole Men.

(©1951 by National Comics Publications, Inc.)

Superman and the Mole Men.

(©1951 by National Comics Publications, Inc.)

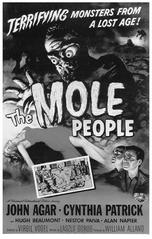

Another semi–hollow earth movie from around the same time, also featuring misunderstood little fellows, was the 1956 subterranean epic,

The Mole People,

which still turns up occasionally on late-late television shows of the Insomniac Stoned Teen Theater variety. This one starred chiseled wooden John Agar, with supporting turns from Hugh Beaumont, later to become Ward Cleaver on

Leave It to Beaver,

and Alan Napier, best remembered as Alfred the butler on television’s

Batman

series in the 1960s.

The Mole People,

which still turns up occasionally on late-late television shows of the Insomniac Stoned Teen Theater variety. This one starred chiseled wooden John Agar, with supporting turns from Hugh Beaumont, later to become Ward Cleaver on

Leave It to Beaver,

and Alan Napier, best remembered as Alfred the butler on television’s

Batman

series in the 1960s.

Agar and his colleagues are archaeologists excavating a site in a remote mountainous part of Asia. They stumble into a hole and find the lost city of Sumeria, ruled by unfriendly albino descendants of ancient Sumer who’ve been living underground since an earthquake relocated their city downward five thousand years earlier. When a tremor clogs their hole with boulders, the archaeologists become trapped and discover that the Sumerians have enslaved an abject and ugly troglodyte-like subterranean race of Mole People, who can dig their way around with a certain ease. The Sumerians, who sacrifice beautiful women to practice birth control and are otherwise downright nasty, have one weakness—they’re pathologically afraid of light. So a single flashlight becomes the archaeologists’ most powerful weapon, until the batteries give out. Elinu, the head Sumerian villain, is about to kill them all. But by then they’ve befriended a few of the Mole People and beautiful Adad, a Sumerian princess. Fortuitously, the Mole People, after suffering thousands of years of oppression, decide right then to stage a slave rebellion. During the chaos, Adad, now in love with Agar, leads the archaeologists to the surface and safety but is killed when a rock pillar falls on her. This, incidentally, was an alternate ending. In the first one they shot, she leaves her underground world hand in hand with Agar; but the studio execs (and this is

really

1956-think) decided that having such a racially mixed couple—both of them white, technically, but she was a little

too

white, I guess—live happily ever after was too controversial, so they killed her off instead. Amazing but true. The story has absolutely no socially redeeming value, or intellectual resonance, except maybe to say that slavery isn’t nice.

really

1956-think) decided that having such a racially mixed couple—both of them white, technically, but she was a little

too

white, I guess—live happily ever after was too controversial, so they killed her off instead. Amazing but true. The story has absolutely no socially redeeming value, or intellectual resonance, except maybe to say that slavery isn’t nice.

The tiny, subterranean Mole People. (©1956 by Universal Pictures, Inc.)

Perhaps most memorable about

The Mole People

is the five-minute introduction, featuring Dr. Frank Baxter. Those of a certain age will remember him as the young people’s television intellectual during the 1950s, genially expounding on matters of presumed scientific interest to kids. That the Dr. before his name came from a Ph.D. in English didn’t seem to matter. Here we find him standing behind a desk in a generic book-lined “academic” office, frequently fondling a globe on the desk in an oddly sensual way, like he’s stroking his girlfriend’s hair, and, yes, delivering a short lecture on the history of the hollow earth—the idea, of course, being to validate and make more believable what’s to come in the movie. He starts with the Sumerians, talks about beliefs regarding subterranean worlds in cultures worldwide, mentions Halley’s theory, and even tells us about John Cleves Symmes and Symmes’ Holes—definitely a movie first, and pretty funny.

The Mole People

is the five-minute introduction, featuring Dr. Frank Baxter. Those of a certain age will remember him as the young people’s television intellectual during the 1950s, genially expounding on matters of presumed scientific interest to kids. That the Dr. before his name came from a Ph.D. in English didn’t seem to matter. Here we find him standing behind a desk in a generic book-lined “academic” office, frequently fondling a globe on the desk in an oddly sensual way, like he’s stroking his girlfriend’s hair, and, yes, delivering a short lecture on the history of the hollow earth—the idea, of course, being to validate and make more believable what’s to come in the movie. He starts with the Sumerians, talks about beliefs regarding subterranean worlds in cultures worldwide, mentions Halley’s theory, and even tells us about John Cleves Symmes and Symmes’ Holes—definitely a movie first, and pretty funny.

Even more so, though, was the 1959 movie version of

A Journey to the Center of the Earth.

The movie stars James Mason as the Professor, and throughout he looks like playing in such a campy production is giving him a migraine headache. Possibly in part because his costar, as his eager young assistant, is Pat Boone.

A Journey to the Center of the Earth.

The movie stars James Mason as the Professor, and throughout he looks like playing in such a campy production is giving him a migraine headache. Possibly in part because his costar, as his eager young assistant, is Pat Boone.

Pat Boone was very big with the teen audience in 1959—the squarer portion of it, at any rate—so casting him, even though he could hardly act, made a certain amount of box office sense. But it would be wasting him if he couldn’t sing, so several

songs

were interspersed into the story. The movie opens, in fact, with Mason being knighted, and a choir of academics, led by Boone, saluting him by singing “Here’s to the Professor of g-e-o-l-o-g-y …” The setting has been moved from Germany to Edinburgh. After two world wars, better to have them be Scotsmen than Germans—though it means having Pat Boone wrestling with a Scottish accent throughout.

songs

were interspersed into the story. The movie opens, in fact, with Mason being knighted, and a choir of academics, led by Boone, saluting him by singing “Here’s to the Professor of g-e-o-l-o-g-y …” The setting has been moved from Germany to Edinburgh. After two world wars, better to have them be Scotsmen than Germans—though it means having Pat Boone wrestling with a Scottish accent throughout.

Verne’s plot was fairly bare-bones, too much so for Hollywood, so several entirely new complications were added—starting with a rival professor who will spare no dastardly deed, including attempted murder, to beat the Professor to the center of the earth. And there has to be a love interest, of course. But in Verne’s novel it was an all-male expedition. Easily fixed. The rival professor is killed off early on, but his sweet wife, played by Arlene Dahl, insists on going along in return for donating all her dead husband’s equipment to the enterprise. She flounces through all the adventures in fancy Victorian dresses, perfect makeup, and carefully coiffed hair. She and Mason hate each other at first, but guess what happens by the end? Taciturn Hans is given a beloved pet duck named Gertrude as a companion, which also cutely quacks her way through the center of the earth with them—until she’s snatched and eaten by minions of the dead evil professor who’ve continued dogging them.

During their trip, they wander into visually splendid additions to Verne’s story—a shining crystal grotto, another that’s phosphorescent, and a remnant of Atlantis replete with fallen pillars and broken temples. Instead of encountering a dinosaur or two, they face herds of them. They escape on a great alabaster bowl left over from Atlantis, which they ride up a lava flow until

plop!

they’re on the surface again. Pat Boone seems to be missing—no, there he is, clothes in tatters, surrounded by a bunch of giggling nuns! Mason observes, “This I know: the spirit of man cannot be stopped.”

plop!

they’re on the surface again. Pat Boone seems to be missing—no, there he is, clothes in tatters, surrounded by a bunch of giggling nuns! Mason observes, “This I know: the spirit of man cannot be stopped.”

The changes are a perfect example of how the hollow earth idea has been repeatedly adapted to suit the needs of the time—in this case, adding elements to make the story conform to movie conventions of the day.

Edgar Rice Burroughs fared even worse.

At the Earth’s Core

seems like Pulitzer Prize material compared to the movie version made in 1976, starring Doug McClure as David Innes and Peter Cushing as Abner Perry. At least

A Journey to the Center of the Earth

had good production values. But the scenery and so-called special effects in

At the Earth’s Core

are so lame they’re almost painful to watch. And Doug McClure has a bonked-on-the-head quality as an actor, generally looking like he’s just coming out of a daze and wondering where he might be, that’s also unfortunate—as are his

very

70s hair and sideburns. The story line remains fairly true to the novel—I think. I confess that I was unable to sit through the whole movie.

At the Earth’s Core

seems like Pulitzer Prize material compared to the movie version made in 1976, starring Doug McClure as David Innes and Peter Cushing as Abner Perry. At least

A Journey to the Center of the Earth

had good production values. But the scenery and so-called special effects in

At the Earth’s Core

are so lame they’re almost painful to watch. And Doug McClure has a bonked-on-the-head quality as an actor, generally looking like he’s just coming out of a daze and wondering where he might be, that’s also unfortunate—as are his

very

70s hair and sideburns. The story line remains fairly true to the novel—I think. I confess that I was unable to sit through the whole movie.

And 1991 saw the release of the animated

Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles at the Earth’s Core,

which is probably enough said about that one. The dated feel of the title alone is a reminder of how quickly kid culture fads come and go.

Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles at the Earth’s Core,

which is probably enough said about that one. The dated feel of the title alone is a reminder of how quickly kid culture fads come and go.

In the past fifteen years or so there’s been a minor resurgence in hollow earth novels. As a literary device it lands entirely in the realm of fantasy adventure—the utopian hollow earth novel is apparently a thing of the past. The most notable of these recent entries are

Circumpolar

(1984) by Richard A. Lupoff,

The Hollow Earth

(1990) by Rudy Rucker, and

Indiana Jones and the Hollow Earth

(1997) by Max McCoy. All three pay conscious homage to accumulated literary conventions regarding the hollow earth—two of them are deliberately old-fashioned pulp-style adventure stories. Only Rucker’s

The Hollow Earth

is particularly memorable, and it is one of the best ever.

Circumpolar

(1984) by Richard A. Lupoff,

The Hollow Earth

(1990) by Rudy Rucker, and

Indiana Jones and the Hollow Earth

(1997) by Max McCoy. All three pay conscious homage to accumulated literary conventions regarding the hollow earth—two of them are deliberately old-fashioned pulp-style adventure stories. Only Rucker’s

The Hollow Earth

is particularly memorable, and it is one of the best ever.

Circumpolar

is set in the 1930s and deliberately imitates the pulp science fiction stories of the period, tossing most of the hollow earth conventions into the pot and stirring once. It’s about a high-stakes airplane race around the poles (ultimately the race leads

through

them) featuring on one team Charles Lindberg, Amelia Earhart, and Howard Hughes; they are up against the unscrupulous von Richtofen brothers, those German flying aces from World War I, and aloof Princess Lvova, a cousin to the late tsar of Russia. All the elements are thrown in—Symmes’ Holes, an underground civilization descended from the progenitors of Norse mythology, prehistoric creatures, ray guns, the works. Clearly meant to be a light-hearted romp, a send-up of the form,

Circumpolar

mainly shows that by now the idea has become degenerate. Not in any moral sense, but rather artistic. It’s pretty much worn out, reality has too far intruded, and it’s now the stuff of parody—and in this case, not an especially successful one.

is set in the 1930s and deliberately imitates the pulp science fiction stories of the period, tossing most of the hollow earth conventions into the pot and stirring once. It’s about a high-stakes airplane race around the poles (ultimately the race leads

through

them) featuring on one team Charles Lindberg, Amelia Earhart, and Howard Hughes; they are up against the unscrupulous von Richtofen brothers, those German flying aces from World War I, and aloof Princess Lvova, a cousin to the late tsar of Russia. All the elements are thrown in—Symmes’ Holes, an underground civilization descended from the progenitors of Norse mythology, prehistoric creatures, ray guns, the works. Clearly meant to be a light-hearted romp, a send-up of the form,

Circumpolar

mainly shows that by now the idea has become degenerate. Not in any moral sense, but rather artistic. It’s pretty much worn out, reality has too far intruded, and it’s now the stuff of parody—and in this case, not an especially successful one.

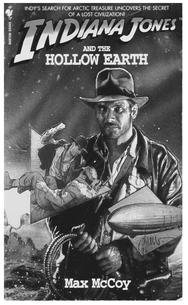

Max McCoy’s

Indiana Jones and the Hollow Earth

belongs to a series of non-movie Indy novels that hearken back to Howard Garis’s efforts for the Stratemeyer Syndicate. It is also set in the 1930s, probably a gambit to make the story more believable. Any parody here seems unintentional. An opening epigraph, the final lines of Poe’s “Ms. Found in a Bottle,” establishes provenance. Indy is at home in Princeton on a bitter winter night when an old man holding a box shows up at his door, on the verge of death. The box contains his journals and an artifact “from an advanced, ancient civilization” found during his explorations of polar regions. Evil Nazis are out to get him—and the box. Indy asks why. “‘Vril! The vital element of this underground world. Matter itself yields to it. With it, one becomes godlike. All but immortal. Pass through solid rock, heal wounds, build cities in a single day—or destroy them. To possess vril is to be invincible.’” Bulwer-Lytton lives! The Nazis want these journals to locate the lost kingdom and terrorize the world with vril. They manage to wrest them from Indy, and the chase is on. Indy is asked to lead an expedition to beat them to it. In the end the Nazis are dead, and the secret of the lost civilization is buried back where it belongs.

Indiana Jones and the Hollow Earth

belongs to a series of non-movie Indy novels that hearken back to Howard Garis’s efforts for the Stratemeyer Syndicate. It is also set in the 1930s, probably a gambit to make the story more believable. Any parody here seems unintentional. An opening epigraph, the final lines of Poe’s “Ms. Found in a Bottle,” establishes provenance. Indy is at home in Princeton on a bitter winter night when an old man holding a box shows up at his door, on the verge of death. The box contains his journals and an artifact “from an advanced, ancient civilization” found during his explorations of polar regions. Evil Nazis are out to get him—and the box. Indy asks why. “‘Vril! The vital element of this underground world. Matter itself yields to it. With it, one becomes godlike. All but immortal. Pass through solid rock, heal wounds, build cities in a single day—or destroy them. To possess vril is to be invincible.’” Bulwer-Lytton lives! The Nazis want these journals to locate the lost kingdom and terrorize the world with vril. They manage to wrest them from Indy, and the chase is on. Indy is asked to lead an expedition to beat them to it. In the end the Nazis are dead, and the secret of the lost civilization is buried back where it belongs.

Indiana Jones and the Hollow Earth

Other books

Guardian of Darkness by Le Veque, Kathryn

Year Zero by Jeff Long

Mexican Nights by Jeanne Stephens

Just One Night, Part 2: Exposed by Davis, Kyra

Unraveling Secrets (The Secret Trilogy) by Lana Williams

Shattered Destiny: A Galactic Adventure, Episode One by Odette C. Bell

Malarky by Anakana Schofield

Reunited with Her Italian Ex by Lucy Gordon

Miami, It's Murder by Edna Buchanan