Hitler Moves East, 1941-1943 (18 page)

Read Hitler Moves East, 1941-1943 Online

Authors: Paul Carell

On 15th August XXIV Panzer Corps moved off again— towards the south—with 3rd and 4th Panzer Divisions in the forefront, followed by 10th Motorized Infantry Division. When the force had successfully broken through the enemy lines the division on the right wing would strike at Gomel. Just the one division—as ordered by the High Command. It was a clever interpretation of the order, and it ensured victory. Guderian made the most of it.

On 16th August the 3rd Panzer Division took the road intersection of Mglin; on the 17th it took the railway junction of Unecha. Thus the railway-line Gomel—Bryansk—Moscow was cut. On 21st August Guderian's two Panzer Corps reached the important jumping-off positions of Starodub and Pochep. All the points were now set for the drive to Moscow. It was on that very day that Hitler called off all plans against the Soviet capital and ordered the advance into the Ukraine.

It was a dramatic turn of events. Its significance was even greater in view of what was happening in the Kremlin.

On 10th August Stalin received a report from his top agent, Alexander Rado, in Switzerland. Rado claimed to have reliable information that the German High Command intended to let Army Group Centre strike at Moscow via Bryansk. The information certainly was reliable : this had been precisely the plan of the German Army High Command.

The effect this report had in Moscow is described in General Yeremenko's memoirs. On 12th August he was instructed by Marshal Timoshenko to come to Moscow at once; he was to take up a new command. Yeremenko writes:

I arrived in Moscow at night and was at once received at the High Command by Stalin and the Chief of the General Staff of the Soviet Army, Marshal Shaposhnikov. Shaposh-nikov briefly outlined the situation at the fronts. His conclusion, based on reconnaissance and other information [no doubt Rado], was that on the central sector an attack on Moscow was imminent from the Mogilev-Gomel area, via Bryansk.

Following Marshal Shaposhnikov's résumé, I. V. Stalin indicated to me on his map the directions of the main enemy offensives and explained that a new strong defensive front must be built up in the Bryansk area as quickly as possible in order to cover Moscow. At the same time, a new striking force must be created for the defence of the Ukraine.

Stalin then asked Yeremenko where he would like to serve. The argument about this point throws an interesting light on the practices of the Soviet General Staff as well as the manner in which Stalin treated his generals. Here is Yeremenko's account:

I replied, "I am prepared to go wherever you send me." Stalin regarded me intently and a shadow of impatience flickered across his features. Very curtly he asked, "But actually?" "Wherever the situation is most difficult," I replied quickly.

"They are both equally difficult and equally complicated— the defence of the Crimea and the line in front of Bryansk," was his reply.

I said, "Comrade Stalin, send me wherever the enemy will attack with armoured units. I believe I can be most useful there. I know the nature and tactics of German armoured warfare."

"Very well," Stalin said, satisfied. "You will leave first thing tomorrow morning and start at once on the establishment of the Bryansk front. Yours is the responsible task of covering the strategic sector of Moscow from the south-west. The drive against Bryansk has been assigned to Guderian's armoured group. He will attack with all his might in order to break through to Moscow. You will encounter the motorized units of your old friend with whose methods you are acquainted from the Central Front."

The assurance with which Stalin expounded the plan of Army Group Centre is astonishing if one remembers how badly the Soviet Command had been informed about the German intentions during the first few weeks of the war.

Naturally, the fact that Moscow was within the zone covered by the German offensive plans was obvious even without secret tip-offs. But the German plan of attack might equally well have envisaged a drive down from the north. Indeed, the High Command Directive No. 34 of 10th or 12th August envisaged this very possibility. Guderian, on the other hand, did not wish to strike via Bryansk, but to drive towards Moscow from the Roslavl area along both sides of the Moscow highway. But the plan of operations submitted to Hitler on 18th August by Colonel-General Halder, Chief of

the Army General Staff, as the proposal of the High Command, included the Bryansk area and agreed exactly with what Stalin told Yeremenko on 12th August.

Stalin believed in the Bryansk-Moscow operation. He believed in Alexander Rado. He continued to believe in him long after Hitler had overthrown the High Command's plan and ordered Guderian's Panzer Group to turn towards the south.

The stubbornness with which the Soviet Command clung to its idea of Moscow being the objective of the German offensive is reflected in the way in which highly revealing evidence by German prisoners of war and the downright alarming discoveries of Russian aerial reconnaissance were dismissed.

Yeremenko writes:

Towards the end of August we took some prisoners who stated under interrogation that the German 3rd Panzer Division, having reached Starodub, was to move to the south in order to link up with Kleist's Panzer Group.

According to these prisoners, the 4th Panzer Division was to keep farther to the right and move parallel with the 3rd Panzer Division. This information was confirmed by our aerial reconnaissance on 25th August, when a massive motorized enemy column was discovered moving in a southerly direction.

The prisoners' evidence was correct. They must have been well-informed troops who supplied this dangerous information to the enemy. It was quite true that on 25th August Guderian had ordered his 3rd and 4th Panzer Divisions as well as the 10th Motorized Infantry Division to cross the Desna river in the area of Novgorod Severskiy and Korop. The 17th Panzer Division and 29th Motorized Infantry Division provided flank cover against Yeremenko's divisions in the Bryansk area.

But the Soviet General Staff and Yeremenko believed in an offensive against Moscow. They regarded Guderian's drive to the south as a large-scale outflanking movement. Yeremenko notes: "From the enemy's operations I concluded that with his powerful advanced units, supported by strong armoured formations, he was engaged in an active reconnaissance and in a manœuvre designed to strike at the flank of our Bryansk front."

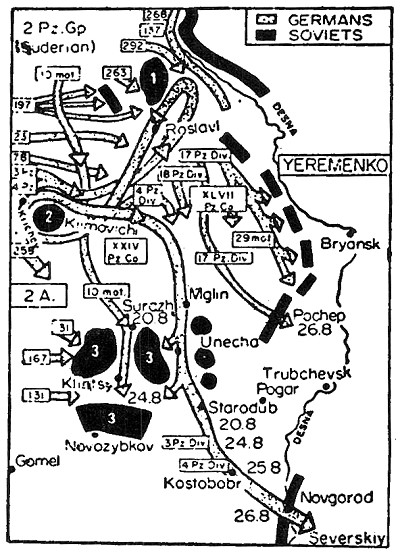

Map 5.

Guderian's drive to the South. In a bold operation Panzer and infantry formations of 2nd Panzer Group and Second Army smashed the Soviets at Roslavl (1), Krichev (2), and in the Gomel area (3), forced the Desna river, and thus initiated the pincer operation against Kiev.A fatal error. Guderian's Panzer divisions pushing to the south did not intend to wheel round towards Moscow, and the 29th Motorized Infantry Division and 17th Panzer Division, which were fighting against Yeremenko's positions in the dangerous, ambush-riddled forests along the road and railway to Bryansk, were not in fact aiming at Bryansk. They were covering Guderian's drive towards the Desna, a drive which was to close the trap behind the Soviet lines at Kiev.. These flank-cover engagements were exceedingly costly. The fierce fighting there is linked with the name of Pochep. There the 167th Infantry Division was involved in heavy defensive fighting. Its 331st Infantry Regiment lost nearly its entire 3rd Company on a single day.

Meanwhile the 3rd Panzer Division, the "Bear" Division from Berlin, was making rapid progress towards the upper reaches of the Desna, a wide, marshy river-course, where Timoshenko had feverishly built up defences during the past few weeks by pressganging the civilian population. During the day the German troops drove or fought, and at night they slept by the roadside, under their tanks or inside their lorries. Their objective was not Moscow but the towns of the Northern Ukraine.

But the Soviet High Command was blind. Stalin not only employed his troops in the wrong direction, he did something far worse. He dissolved the Soviet central front with its Twenty-first and Third Armies—the front which formed a barrier across the Northern Ukraine—and placed the divisions under Yeremenko's Army Group for the defence of Moscow. Yeremenko remarks bitterly: "The High Command informed us once more that Guderian's blow was aimed at

the right wing of the Bryansk front—in other words, against Moscow. On 24th August Comrade Shaposhnikov notified me that the attack was to be expected within the next day or two."

They waited for it in vain. Yeremenko's account continues:

However, this assumption was not borne out. The enemy attacked in the south and merely brushed against our right wing. At that time neither the High Command nor the command in the field had any evidence that the direction of the offensive of the German Army Group Centre had been changed and turned towards the south. This grave error by the General Staff led to an exceedingly difficult situation for us in the south.

Hitler and Stalin seemed to vie with each other in frustrating the work of their military commanders by fatal misjudg- ments. So far, however, only Stalin's mistakes were becoming obvious.

The date was 25th August, It was a hot day and the men were sweating. The fine dust of the rough roads enveloped the columns in thick clouds, settled on the men's faces, and got under their uniforms on to their skins. It covered the tanks, the armoured infantry carriers, the motor-cycles, and the jeeps with an inch-thick layer of dirt. The dust was frightful

—as fine as flour, impossible to keep out.

The 3rd Panzer Division had been moving down the road from Starodub to the south for the past five hours. Its commander, Lieutenant-General Model, was in his jeep at the head of his headquarters group, which included an armoured scout-car, the radio-van, motor-cycle orderlies, and several jeeps for his staff. The infantrymen cursed whenever the column tore past them, making the dust rise in even thicker clouds.

Model, leading in his jeep, pointed to an old windmill on the left of the road. The jeep swung over a little bridge across a stream and drove into a field of stubble. Maps were brought out; a headquarters staff conference was held on the bare ground. The radio-van pushed up its tall aerials. Motor-cycle orderlies roared off and returned. Model's driver went down to the stream with two field-buckets to get some water for washing. Model polished his monocle. Bright and sparkling, it was back in his eye when Lieutenant-Colonel von Lewinski, CO of 6th Panzer Regiment, came to report. A Russian map, scale 1:50,000, was spread out on a case of hand-grenades.

"Where is this windmill?" "Here, sir." Model's pencil-point ran from the hill with the windmill right across on to the adjoining sheet which the orderly officer was holding. The pencil line ended by the little town of Novgorod Severskiy.

* "How much farther?"

The Intelligence officer already had his dividers on the map. "Twenty-two miles, Herr General."

The radio-operator brought a signal from the advanced detachment. "Stubborn resistance at Novgorod. Strong enemy bridgehead on the western bank of the Desna to protect the two big bridges."

"The Russians want to hold the Desna line." Model nodded.

Certainly they wanted to. And for a good reason. The Desna valley was an excellent natural obstacle, 600-1000 yards wide. Enormous bridges were needed for crossing the river and its swampy banks. The big road-bridge at Novgorod Severskiy was nearly 800 yards long, and the smaller pedestrian bridge was not much shorter. Both were wooden bridges, and neither of them, according to the division's aerial reconnaissance squadron, had been blown up so far. But they were being defended by strong forces.

"We must get one of those bridges intact, Lewinski," Model said to the Panzer Regiment commander. "Otherwise it'll take us days, or even weeks, to get across this damned river." Lewinski nodded. "We'll do what we can, Herr General." He saluted and left.

"Let's go," Model said to his staff. As the main route of advance was congested with traffic the divisional staff drove along deep sandy forest tracks. Through thick woods their vehicles scrambled thirty miles deep into enemy territory. They might find themselves under fire at any moment. But if one were to consider that possibility one would never make any progress at all.

From ahead came the noise of battle. The armoured spearheads had made contact with the Russians. Motor-cycle troops were exchanging fire with Russian machine-guns. The artillery was moving into position with one heavy battery. Through his field-glasses Model could see the towers of the beautiful churches and monasteries of Novgorod Severskiy on the high ground on the western bank of the river. Beyond those heights was the Desna valley with its two bridges.

Russian artillery opened fire from the town. Well-aimed fire from 15-2-cm. batteries. The artillery was the favourite arm of the Soviets—just as it had been that of the Tsars. "Artillery is the god of war," Stalin was to say in a future Order of the Day. The plop of mortar batteries now mingled with the general noise. A moment later the first mortar- bombs were crashing all around. Model was injured in one hand by a shell-splinter. He had some plaster put on—that was all. But a shell got Colonel Ries, the commander of 75th Artillery Regiment. He died on the way to the dressing- station.

Low-level attack by Russian aircraft. "Anti-aircraft guns into action!" The enemy's artillery was now finding its range. Time to change position.

The 6th Panzer Regiment and the motor-cycle battalion launched their attack that very evening at dusk. But the tanks were held up by wide anti-tank ditches with tree-trunks rammed in. The infantry regiment which was to have attacked the Russians from the north-west at the same moment had got stuck somewhere on the sandy roads.

Everything stop! The attack was postponed until the following morning.

At 0500 everything flared up again. The artillery used its heavy guns to flatten the anti-tank obstacles. Engineers blasted lanes through them. Forward! The Russians were fighting furiously and relentlessly in some places, but in others their resistance was half-hearted and incompetent. The first troops began to surrender—men between thirty-five and forty-five, largely without previous military service and with no more than a few days' training now. Naturally they did not stand up to the full-scale German attack—not even with the commissars behind them. German tanks, self- propelled guns, and motor-cycle infantry drove into the soft spots.

At 0700 hours First Lieutenant Vopel, with a handful of tanks from his 2nd Troop and with armoured infantry-carriers of 1st Company, 394th Rifle Regiment, took up a position north of Novgorod Severskiy. His task was to give support to an engineers assault detachment under Second Lieutenant Störck in their special operation against the big 800-yard- long wooden bridge. First Lieutenant Buchterkirch of 6th Panzer Regiment, who was Model's specialist in operations against bridges, had joined the small combat group with his tanks. Towards 0800 a huge detonation and cloud farther south indicated that the Russians had blown up the smaller bridge.

Everything now depended on Storck and Buchterkirch's operation.

Storck and his men in the armoured infantry-carriers took no notice whatever of what was happening to the right or left of them. They shot their way through Russian columns. They raced across tracks knee-deep in sand. Under cover of the thick dust-clouds they infiltrated among retreating Russian columns of vehicles. They drove through the northern part of the town. They raced down into the river valley to the huge bridge.

Other books

Lady by Thomas Tryon

Return to Willow Lake by Susan Wiggs

Holly's Jolly Christmas by Nancy Krulik

Breaking Kate: The Acceptance Series by Kelly, D.

The One and Only Ivan by Katherine Applegate

Prophecy. An ARKANE thriller. (Book 2) by J.F. Penn

This Common Secret: My Journey as an Abortion Doctor by Susan Wicklund

Mate Marked: Shifters of Silver Peak by Georgette St. Clair

Broken Beauty by Chloe Adams

Surface Detail by Banks, Iain M.