Hitler Moves East, 1941-1943 (105 page)

Read Hitler Moves East, 1941-1943 Online

Authors: Paul Carell

Field-Marshal von Manstein merely shook his head, aghast. Then a suspicion of a smile flickered round his lips. He decided to overlook the whole thing, but forbade all further "tank-swiping" in future. "We passed on some of our tanks to 6th and 23rd Panzer Divisions, and from then onward employed our own armoured units in no more than company strength so that they should not attract attention from higher commands."

In this manner the wide breach which the Soviet offensive had torn in the German front in the rear of Sixth Army was sealed again. It was a tremendous triumph of leadership. For weeks a front about 120 miles long was held by formations consisting largely of Reich railway employees, Labour Servicemen, construction teams of the Todt Organization, and of volunteers from the Caucasian and Ukrainian Cossack tribes.

It should also be recorded that numerous Rumanian units which had lost contact with their Armies placed themselves under German command. There, under German leadership and, above all, with German equipment, they often acquitted themselves excellently, and many of them remained with these German formations for a long time at their own request.

The first major regular formation to reach the Chir front arrived at the end of November, when XVII Army Corps under General of Infantry Hollidt fought its way into the area of the Rumanian Third Army. Everybody heaved a sigh of relief.

At Wenck's suggestion Army Group now subordinated to General Hollidt the entire Don-Chir sector with all formations which had been fighting there; these were formed into the "Armeeabteilung Hollidt." Thus the motley collection of units known to the troops as "Wenck's Army" ceased to exist. It had accomplished a task with few parallels in military history. Its achievement, moreover, provided the foundation for the second act of the operations on the Chir—the recapture of the high ground on the river's south-western bank, indispensable for any counter-attack.

This task was accomplished at the beginning of December by the 336th Infantry Division brought up for the purpose and by the 11 th Panzer Division following behind it.

The high ground was taken in fierce fighting and held against all Soviet attacks. These positions on the Chir were of vital importance for the relief of Stalingrad as planned by Manstein, an offensive for which the Field-Marshal employed Hoth's Army-sized combat group from the Kotelnikovo area east of the Don. The Chir front provided flank and rear cover for this rescue operation for Sixth Army. More than that—as soon as the situation permitted XLVIII Panzer Corps, now under the command of General of Panzer Troops von Knobels-dorff, was to support Hoth's operation by attacking in a northeasterly direction with llth Panzer Division, 336th Infantry Division, and a Luftwaffe field division. The springboard for this auxiliary operation was to be Sixth Army's last Don bridgehead at Verkhne-

Chirskaya, at the exact spot where the Chir ran into the Don. There Colonel Adam, General Paulus's Adjutant, was holding this keypoint with hurriedly collected

ad hoc

units of Sixth Army in truly heroic 'hedgehog' fighting. Thus all steps were being taken and everything humanly possible was being done at this eleventh hour by dint of courage and military skill to rectify Hitler's great mistake and to rescue the Sixth Army.- Hoth launches a Relief Attack

"Winter Storm" and "Thunder-clap"-The 19th December-Another 30 miles—Argument about "Thunder-clap"— Rokossov-skiy offers honourable capitulation.

ON 12th December Hoth launched his attack. The task facing this experienced, resourceful, and bold tank commander was difficult but not hopeless.

Hoth's right flank had been secured, like the line on the Chir, by drastic means. Colonel Doerr, who was Chief of the German Liaison Staff with the shattered Rumanian Fourth Army, had built up a thin covering line with

ad hoc

units and scraped-together parts of German mobile formations, in much the same way as Colonel Wenck had done in the north. The combat groups under Major Sauvant with units of 14th Panzer Division, and under Colohel von Pannwitz with his Cossacks, flak units, and

ad hoc

formations, restored some measure of order among the retreating Rumanian troops and the German rearward services to whom the panic had spread.The 16th Motorized Infantry Division retreated from the Kalmyk steppe to prepared positions. In this way it also proved possible on the southern wing to foil Russian attempts to strike from the east at the rear of the Army Group Caucasus and to cut it off.

One would have thought that Hitler would now have made available whatever forces he could for Moth's relief attack, to enable him to strike his liberating blow across 60 miles of enemy territory with the greatest possible vigour and speed. But Hitler was again stingy with his formations. With the exception of 23rd Panzer Division, which was coming up under its own steam, he did not release any of the forces in the Caucasus. The only fully effective formation allocated to Hoth was General Raus's 6th Panzer Division with 160 tanks, which had to be brought from France. It arrived on 12th December with 136 tanks. The 23rd Panzer Division arrived with 96 tanks.

Sixty miles was the distance Hoth had to cover—60 miles of strongly held enemy territory. But things started well. Almost effortlessly the llth Panzer Regiment, 6th Panzer Division, under its commander Colonel von Hunersdorff on the very first day dislodged the Soviets, who fell back to the east. The Russians abandoned the southern bank of the Aksay, and Lieutenant-Colonel von Heydebreck established a bridgehead across the river with units of 23rd Panzer Division.

The Soviets were taken by surprise. Colonel-General Yere-menko telephoned Stalin and reported anxiously: "There is a danger that Hoth may strike at the rear of our Fifty-seventh Army which is sealing off the south-western edge of the Stalingrad pocket. If, at the same time, Paulus attacks from inside the pocket, towards the south-west, it will be difficult to prevent him from breaking out."

Stalin was angry. "You will hold out—we are getting reserves down to you," he commanded menacingly. "I'm sending you the Second Guards Army—the best unit I've left."

But until the Guards arrived Yeremenko had to manage alone. From his ring around Stalingrad he pulled out the XIII Armoured Corps and flung it across the path of Hoth's 6th Panzer Division. He also ruthlessly denuded his Army Group of its last reserves and threw in the 235th Tank Brigade and the 87th Rifle Division against the spearheads of Hoth's attack. Fighting for the high ground north of the Aksay went on for five days. Fortunately for Hoth, the 17th Panzer Division, which Hitler had at last made available, arrived just in time. Consequently the enemy was dislodged on 19th December.

After a memorable all-night march the armoured group of 6th Panzer Division reached the Mishkova sector at Vasily- evka in the early morning of 20th December. But Stalin's Second Guards Army was there already. Nevertheless General Raus's formations succeeded in establishing a bridgehead two miles deep. Only 30 to 35 miles as the crow

flew divided Hoth's spearheads from the outposts of the Stalingrad front.

What meanwhile was the situation like inside the pocket? The supply position of the roughly 230,000 German and German-allied troops was pitiful. It soon turned out that the German Luftwaffe was in no position to keep a whole Army in the depth of Russia supplied from temporary air-strips in mid-winter. There were not enough transport aircraft. Bombers had to do service as transport machines. But these could not carry more than 1V4 tons of cargo. Moreover, their withdrawal from operational flying had unpleasant consequences in all sectors of the front. Once again the crucial problem of the campaign was clearly revealed: Germany's material strength was insufficient for this war.

General von Seydlitz had put the daily supply requirements at 1000 tons. That was certainly too high. Sixth Army regarded 600 tons as desirable and 300 tons as the minimum figure for keeping the Army in some sort of fighting condition. Bread requirements alone for the defenders in the pocket amounted to forty tons a day.

Fourth Air Fleet tried to fly in these 300 tons a day. Lieutenant-General Fiebig, the experienced Commander of VIII Air Corps, was assigned this difficult task—and at first it looked as though it could be accomplished. Soon, however, frost and bad weather proved insuperable enemies, more dangerous than Soviet fighters or the Soviet heavy flak. Icing up, poor visibility, and the resulting accidents caused more casualties than enemy action. Nevertheless the air crews displayed a dash and gallantry as in no previous operation. Never before in the history of flying had men set out with such disdain of death and such firm resolution as for the supply airlift to Stalingrad. Some 550 aircraft were totally lost. That means that one-third of the aircraft employed were lost together with their crews—the victims of bad weather, fighters, and flak. One machine in every three was lost—a terrifying rate which no air power in the world could have kept up.

Only on two occasions was the minimum cargo of 300 tons delivered—or very nearly so. On 7th December, according to the diary of the Chief Quartermaster of Sixth Army, 188 aircraft landed at the airfield of Pitomnik and delivered 282 tons. On 20th December the figure was 291 tons. According to Major-General Herhudt von Rohden's excellent essay, based on the records of the Luftwaffe, the peak day of the airlift was 19th December, when 154 aircraft delivered 289 tons of supplies to Pitomnik and evacuated 1000 wounded.

On an average, however, the daily deliveries between 25th November and llth January totalled 104-7 tons. During that period a total of 24,910 wounded were evacuated. At this rate of supplies the men in the pocket had to go hungry and were seriously short of ammunition.

Nevertheless the divisions held out. To this day the Soviets have not published any definite figures of German deserters. But according to all available German sources their number, until mid-January, must have been negligible. Indeed, as soon as the news spread among the troops that Hoth's divisions had launched their relief attack a real fighting spirit spread among them. There was hardly a trooper or an officer who was not firmly convinced that Manstein would get them out. And even the most battle-weary battalion felt strong enough to strike at the ring of encirclement to meet their liberators half-way. That such a plan existed was generally known inside the pocket. After all, units of two motorized divisions and one Panzer division were standing by on the southern front of the pocket, ready to strike in the direction of Hoth's divisions the moment these were close enough and the order for "Winter Storm" was given.

The afternoon of 19th December was cold but clear—magnificent flying weather. Over Pitomnik there was a continuous roar of transport aircraft. They touched down and unloaded their cargoes, were packed full with wounded, and took off again. Petrol-drums were piled high, packing-cases were stacked on top of one another. Shells were trundled away. If only they had this kind of weather every day!

Twenty-four hours earlier an emissary from Manstein had arrived in the pocket in order to acquaint Army with the Field-Marshal's ideas about the break-out. Major Eismann, the Intelligence Officer of Army Group Don, had meanwhile flown back again. No one suspected as yet that his visit was to become an irritating episode in the Stalingrad tragedy— simply because no written record is extant of the conversations, and the account written by the major from memory ten years later has given rise to many conflicting theses. To this day it has not been definitely established what Paulus, Schmidt, and Eismann really said and what they meant. Did Eismann convey clearly and

accurately Manstein's view that the present situation offered only the brutal alternative of early break-out or annihilation? Did he convey clearly that Hollidt's group on the Chir was so busy defending itself against Soviet counter-attacks that there could be no question of its launching an attack in support of Hoth? Did he report that ever- stronger Soviet formations were being deployed against Hoth? Above all, did he state unambiguously that the Field- Marshal was entirely clear about one thing—that the break-out demanded the surrender of Stalingrad in several stages, no matter what label was given to the operation, in order not to arouse Hitler's suspicions too soon? And what did Paulus and Schmidt say in reply? Questions and more questions—and none of them capable of being answered to-day, Eismann's mission is likely to engage the attention of military historians for a long time yet.

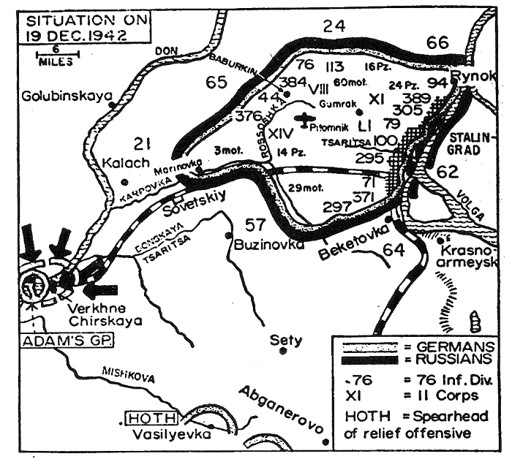

Map 35.

The Stalingrad pocket before the Soviet full-scale attack.The 19th December might be called the day of decision, the day when the drama of Stalingrad reached its culmination. Paulus and his chief of staff, Major-General Schmidt, were standing in the dugout of the Army chief of operations, in front of a teleprinter which had been connected to a decimetre-wave instrument, a radio circuit which could not be monitored by the Soviets. In this way Sixth Army had an invaluable, even though technically somewhat cumbersome, direct line to Army Group Don in Novocherkassk.

Paulus was waiting for the arranged contact with Manstein. Now the time had come. The machine started ticking. It

wrote: "Are the gentlemen present?"

Paulus ordered the reply to be sent: "Yes." "Will you please comment briefly on Eismann's report," came the message from Manstein.

Paulus formulated his comment concisely.

Alternative 1: Break-out from pocket in order to link up with Hoth is possible only with tanks. Infantry strength lacking. For this alternative all armoured reserves hitherto used for clearing up enemy penetrations must leave the fortress.

Alternative 2: Break-out without link-up with Hoth is possible only in extreme emergency. This would result in heavy losses of material. Prerequisite is preliminary flying-in of sufficient food and fuel to improve condition of troops. If Hoth could establish temporary link-up and bring in towing vehicles this alternative would be easier to carry out.

Infantry divisions are almost immobilized at moment and are getting more so every day as horses are slaughtered to feed men.

Alternative 3: Further holding out in present situation depends on aerial supplies on sufficient scale. Present scale utterly inadequate.

And then Paulus dictated into the teleprinter: "Further holding out on present basis not possible much longer." The teleprinter tapped three crosses.

A moment later Manstein's text came ticking through: "When at the earliest could you start Alternative 2?" Paulus answered: "Time needed for preparation three to four days."

Manstein asked: "How much fuel and food required?"

Paulus replied: "Reduced rations for ten days for 270,000 men."

The conversation was interrupted. A quarter of an hour later, at 1830 hours, it was resumed, and Manstein and Paulus once more talked to each other through the keyboards of their teleprinters. In a strangely anonymous way the words appeared, clicking, on the paper:

"Colonel-General Paulus here, Herr Feldmarschall." "Good evening, Paulus."

Manstein reported that Hoth's relief attack with General Kirchner's LVII Panzer Corps had got as far as the Mishkova river.

Paulus in turn reported that the enemy had attacked his forces concentrated for a possible break-out at the southwestern corner of the pocket.

Manstein said: "Stand by to receive an order."

A few minutes later the order came clicking over the teleprinter. This is what it said: Order!

To Sixth Army.

- Fourth Panzer Army has defeated the enemy in the Verkhne-Kumskiy area with LVII Panzer Corps and reached the Mishkova sector. An attack has been initiated against a strong enemy group in the Kamenka area and north of it. Heavy fighting is to be expected there. The situation on the Chir front does not permit the advance of forces west of

the Don towards Stalingrad. The Don bridge at Chirskaya is in enemy hands.

- Sixth Army will launch attack "Winter Storm" as soon as possible. Measures must be taken to establish link-up with LVII Panzer Corps if necessary across the Donskaya Tsaritsa in order to get a convoy through.

- Development of the situation may make it imperative to extend instruction for Army to break through to LVII Panzer Corps as far as the Mishkova, Code name: "Thunderclap." In that case the main task will again be the quickest possible establishment of contact, by means of tanks, with LVII Panzer Corps with a view to getting convoy through. The Army, its flanks having been covered along the lower Karpovka and the Chervlenaya, must then be moved forward towards the Mishkova while the fortress area is evacuated section by section.

Operation "Thunder-clap" may have to follow directly on attack "Winter Storm." Aerial supplies will, on the whole, have to be brought in currently, without major build-up of stores. Airfield of Pitomnik must be held as long as possible.

All arms and artillery that can be moved at all to be taken along, especially the guns needed for the operation, and to be ammunitioned, but also such weapons and equipment as are difficult to replace. These must be concentrated in the southwestern part of the pocket in good time.

- Preparations to be made for (3). Putting into effect only upon express order "Thunder-clap."

- Report day and time of attack (2).

- Fourth Panzer Army has defeated the enemy in the Verkhne-Kumskiy area with LVII Panzer Corps and reached the Mishkova sector. An attack has been initiated against a strong enemy group in the Kamenka area and north of it. Heavy fighting is to be expected there. The situation on the Chir front does not permit the advance of forces west of

Other books

The Teleporter. by Arthur-Brown, Louis

His One Woman by Paula Marshall

Faking Sweet by J.C. Burke

14 BOOK 2 by J.T. Ellison

Twisted Shadows by Potter, Patricia;

The Deeper He Hurts by Lynda Aicher

King Of Souls (Book 2) by Matthew Ballard

Bears! Bears! Bears! by Bob Barner

Christopher and His Kind by Christopher Isherwood

Empire Rising by Sam Barone