Hitching Rides with Buddha: A Journey Across Japan (47 page)

Read Hitching Rides with Buddha: A Journey Across Japan Online

Authors: Will Ferguson

The ferry to Hokkaido was a floating hotel with potted plants and polished mirrors. It foghorned its way out of Aomori harbour, past the grey silhouettes of trawlers and oil refineries. On either side, the pincer claws of Aomori’s northern peninsulas closed in as we slid free like a lover escaping an embrace.

I pulled my hood down and stood on the deck, face in the wind, the taste of salt water in the air. I might have stayed out there in my heroic pose for the entire crossing, but the winds were cold and I had to pee.

Inside, there was only the hum and throb of the engines and that suffocating silence of a ferry at night. Bodies were asleep at all angles, as though nerve gas had swept through the cabin. I wandered among strangers and ended up sharing a room with a cigarette-smoking, swampy-eyed man and a woman who scowled in her sleep.

I

NTO A

N

ORTHERN

S

EA

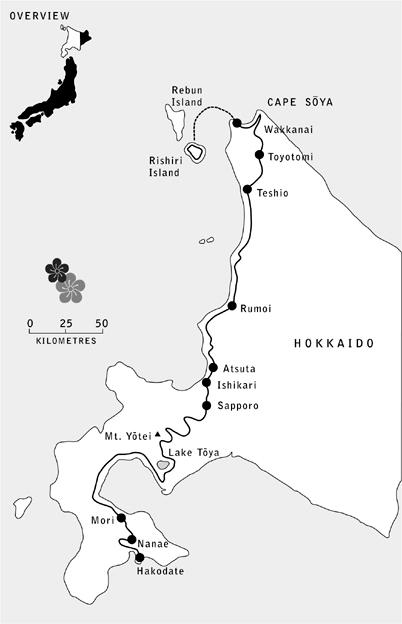

Across Hokkaido

1

H

OKKAIDO IS A VAST

, underpopulated island with a climate that is closer to Oslo’s than to Tokyo’s. The summers are short and the winters are long; this is a place that sees icebergs off its northern coast.

In many ways, Hokkaido is the least “Japanese” of all the main islands. It’s Texas and Alaska rolled into one. The last frontier and the end of Japan. It was not formally colonized until after the Meiji Reformation of 1868, and even then it wasn’t completely opened up by settlers until the 1880s—at about the same time that the American Wild West was at its peak, with Wyatt Earp and Doc Holliday blasting away at the OK Corral. Hokkaido even

looks

like the American West.

This is cattle country, with rolling fields, high mountains, and shimmering Texas-style metropolises. They even have their very own oppressed aboriginal minority, the Ainu. The Ainu were seafarers, fur trappers, and hunters, and though they had no written language, they passed down

yukar

, epic sagas, from generation to generation. They worshipped the bear, they tattooed themselves in elaborate—almost Celtic—patterns, they built a complex system of salmon weirs and lived in interconnecting communities along the northern riverways.

Where the Ainu came from remains something of a mystery. The consensus seems to be that they migrated from the Siberian steppes. Their skin is paler than that of most Asian people, but they are not—as many commentators purport—Caucasian. Nor are they particularly “hairy.” (The fact that the Japanese describe the Ainu as being hairy—and, as often as not, “smelly”—says

more about Japanese prejudices than it does about actual Ainu physiognomy.)

Although not formally conquered, the Ainu in the northern regions were brought under heel by the early shōguns. In 1669 an Ainu uprising was crushed, and for two hundred years they remained a subjugated population. It was only in the late nineteenth century that they were annexed as a people—and as an island. The Ainu were stripped of their ancestral rights, forced onto farmlands and into enclaves, and made to renounce their religion and culture. Their language was banned, and they were deemed “non-citizens.”

The Ainu were not officially recognized as being Japanese citizens until 1992. Even then, the Japanese government refuses to use the term

indigenous

when discussing the Ainu (to avoid having to accept responsibility for what happened and to stave off growing demands for a land claims settlement). An important point: the Ainu never ceded their homelands nor ever acknowledged Japanese authority, making them one of the few aboriginal groups in the world that have never been offered a treaty by the people who invaded their territory. In a nation like Japan, which has decreed itself “racially and culturally homogenous,” people like the Ainu simply do not enter the paradigm/mythology. At best, they are a novelty, a source of amusement. At worst, they are simply pests.

Today, twenty-four thousand people claim Ainu ancestry, but few are pure-blooded and their language is all but dead, thanks largely to a relentless and concentrated campaign of assimilation mounted by the Japanese government. The Ainu influence appears to have once extended quite far south into Honshu—the “Fuji” in Mount Fuji is thought to be of Ainu origin—but the present-day Ainu have been reduced to a tawdry tourist sideshow. Ainu elders sit stoically baring their tattoos like lepers on display while Japanese tourists giggle and pose beside them for photographs. It is very dispiriting, these human zoos, and it was one of the reasons I decided to avoid the main tourist areas around Akan Lake, once an Ainu heartland and now, well

—not

an Ainu heartland.

A stubborn renaissance of Ainu culture has taken root lately, primarily around the music, legends, and dance, but overall the situation is fragile. Australian Aborigines, North American Natives, South

American Indians—there is something in the psyche of the colonist that is unnerved by prior ownership, as we patronize, brutalize, ignore, and then wax poetic about the people we displace.

It was with thoughts like these that I entered Hokkaido to begin the last leg of my journey.

2

A

T THE SOUTHERN TIP

of Hokkaido lies a small hook of land anchored at one end by a dormant volcanic peak. It was here, upon this geographical anomaly, that Hokkaido’s first Japanese settlement began, an imperial toehold on the great island above. The Russians had been using Hakodate Port as a landing base as far back as 1740. In 1854, Japan moved in to counter Russian expansion. Hakodate became an open city and, for one brief period, while the imperial powers moved their chess pieces into position and the fate of the northern island hung in the balance—for one brief period, Hakodate was a centre of intrigue and power.

Today, Hakodate has fallen half asleep. A threadbare, somewhat seedy city, it is one of the few areas in Hokkaido where the American influence doesn’t dominate. Here the flavour is European—

eastern

European. Russian architectural styles are everywhere in evidence, even though the people are resolutely Japanese.

Hakodate is a city of endgames, where history begins and empires fade. It was here, in Hakodate, that the forces of the Shōgun made their fateful last stand. It was here, in the Battle of Hakodate, that the troops of the Tokugawa shōguns were finally defeated by the upstart civilian army of the newly modernized Emperor Meiji. It was the last hurrah of the samurai class, and it brought to an end two hundred and fifty years of the shōgun rule. In its stead was an outward-looking, imperially minded

modern

government. The Battle of Hakodate centred on the city’s star-shaped British citadel, and the irony was sharp: a European-style fortress would be the last refuge of the samurai.

—

I arrived in Hakodate late in the evening, and I found a room at a bed-and-breakfast called the Niceday Inn. When I entered, the owner received me with boisterous English. “Come in! Come in!”

His name was Shigeto Saito. “But call me Mr. Saito,” he said, generously. He had the face of a boxer who has seen one too many fights. Heavy, lugubrious features. (I’m not really sure what “lugubrious features” means, but if anyone had them, it was Mr. Saito.) “Welcome to my small inn. I hope you find it comfortable.”

“Your English is very good,” I said. “Do you study?”

“Self-taught,” he said. “Completely self-taught.” And then, anticipating my next question, “Why? Why so good? Because I never had a fear of foreigners. Never. I don’t have a complex. Most Japanese are afraid.”

“Shy,” I said.

“Afraid,”

he insisted. “But why, of all people, did I not develop a complex? Why?” We sat back to consider this. It was a question he had clearly puzzled over for some time. “I have a theory,” he said after a suitable pause. “When I was a child, Russian sailors would come into port. My father was involved in business, and the Russians often came to our house. My mother was very nervous; she would hide in the back room. But the Russians liked me, a little boy. Maybe they have children also back home. Who knows? They used to pick me up and speak to me. Big hands. Loud voices. I was so small a child. But I remember it very well. Looking up at them, at their faces. Sitting on their knee. Hearing their big Russian laughter. Maybe that is why. Maybe that is why I never developed a complex. That early experience broke the barrier.”

I thought this was a fine theory, and we toasted it with Japanese vodka. My liver began whimpering again, but what the hell, how often do you have a chance to be enlightened by the likes of Mr. Saito, innkeeper and self-taught speaker of English in a Russian town on a Japanese island that was taken from Ainu natives?

Mr. Saito’s wife stopped in and we chatted a bit in Japanese. Mr. Saito listened with a keen ear, and as soon as his wife excused herself, he leaned over and said to me—in what would be the first and only honest assessment I would ever receive of my second-language ability—“Your Japanese is terrible.”

“Um.” (What could I say?)

“Your accent is very thick. That is from living in Kyushu.” (The idea being, I had been infected by living amidst such a poor dialect.) “Here in Hokkaido, everyone originally came from somewhere else. We soon lost our different accents. In Hokkaido, we speak Standard Japanese. Some people say that our Japanese is the finest in Japan. You should study

Hokkaido

Japanese. And you also need to study”—we consulted a dictionary for the right word—“the prepositions. You know

ga, wa, ni, de, no

. I was listening to you speak Japanese, and it sounds like you just put them in at random.”

Damn. He was on to me. I hated Japanese prepositions. I hated them with a passion, and I did indeed use them at random, much like a slot machine, hoping they would occasionally come up correct. This had also been my approach to the feminine and masculine in French, just picking either

le

or

la

at random and crossing my fingers.

“Well, I would like to study Japanese more,” I lied. “Someday, I’d like to become completely fluent.”

“Fluent?” He raised an eyebrow. “No, no. Not fluent. Big mistake. We Japanese don’t trust foreigners who speak our language perfectly. It makes us nervous. You should improve your Japanese, but never,

never

become completely fluent.”

I promised him I wouldn’t. “But only if you insist,” I said.

I was shown to my room. It was dormitory-style with four bunk beds and crisp sheets freshly turned down. The only other occupant that night was a large, sad-eyed beanbag of a man. He was in Hakodate for some unspecified reason and was clearly not happy with being placed in the same room as a foreigner. He put on a brave face, he even smiled at me in a sorrowful, fatalistic way, but when he battened down for the night I noticed he carefully drew his bags in around him and hid his wallet under his pillow. Not to be outdone, I did the same thing with my bags—just to let him know that I was perfectly aware of what was going on. (This is how wars start.)

Travel fatigue hit me in a wave of yawns and sighs, and I fell into sleep like a body down a well. It was a deep, rich, chocolate sort of slumber, and it lasted all of—oh, ten minutes, before I was jolted awake by the sound of an asthmatic seagull being throttled to death by a mad bagpiper. It was my roommate. He was snoring.

Loudly

. So loudly, the walls were being sucked inward with each inhalation and bulging outward with each exhalation. In between, he made this

high-pitched gawking sound that set my nerves on edge. I wrapped a pillow around my head, and I was considering my options—murder, madness, insomnia—when the man stopped breathing. Entirely. I had heard of sleep apnea, but this was alarming. It lasted for long, agonizing minutes and now, damn it all to hell, I couldn’t sleep because of the silence. (It’s hard to drift off when you may be sharing a room with a corpse.) A few minutes later he started breathing again with a startled gasp, and I relaxed ever so slightly. With a mumbled moan, he rolled over and began releasing farts into the blankets like depth charges.