History of the Second World War (97 page)

Read History of the Second World War Online

Authors: Basil Henry Liddell Hart

Tags: #History, #Military, #General, #Other

* North:

The Achievements of 21st Army Group,

p. 115.

The best chance of a quick finish was probably lost when the ‘gas’ was turned off from Patton’s tanks in the last week of August, when they were 100 miles nearer to the Rhine, and its bridges, than the British.

Patton had a keener sense than anyone else on the Allied side of the key importance of persistent pace in pursuit. He was ready to exploit in any direction — indeed, on August 23 he had proposed that his army should drive north instead of east. There was much point in his subsequent comment: ‘One does not plan and then try to make circumstances fit those plans. One tries to make plans fit the circumstances. I think the difference between success and failure in high command depends upon its ability, or lack of it, to do just that.’

But the root of all the Allied troubles at this time of supreme opportunity was that none of the top planners had foreseen such a complete collapse of the enemy as occurred in August. They were not prepared, mentally or materially, to exploit it by a rapid long-range thrust.

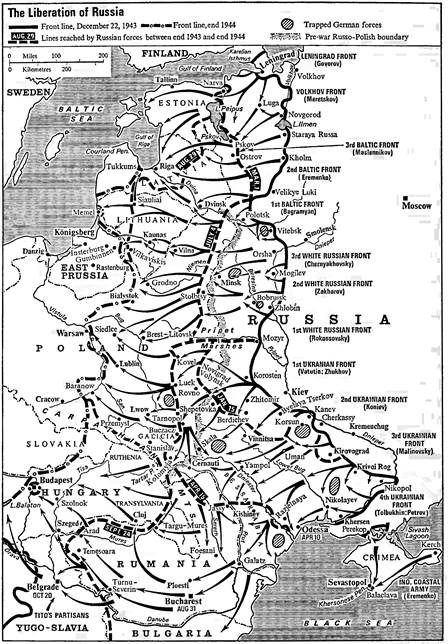

CHAPTER 32 - THE LIBERATION OF RUSSIA

The campaign on the Eastern Front in 1944 was governed by the fact that, as the Russians advanced, the front remained as wide as ever while the German forces were shrinking — with the natural result that the Russian advance continued with little check except from its own supply problem. The course of events provided the clearest possible demonstration of the decisive importance of the ratio between space and force. Moreover, the pauses in the progress were the measure of the space over which the Russian supply lines had to be brought forward.

The main campaign consisted of two great Russian spurts, on alternate wings, each followed by a long pause. The first was in midwinter and the second in midsummer. In the subsidiary campaign that developed with the extension of the southern flank, through central Europe, the pauses were shorter — a difference largely explained by the fact that there the ratio of space to the German forces was greater than in the main theatre, so that the Russian forces needed less of a build-up before tackling each of the successive German defence-lines.

The winter offensive saw an opening move similar to that of the autumn, and the similar effect it produced was evidence not so much of the Germans’ miscalculation as of their decreasing ability to ‘make ends meet’. Early in December 1943 Koniev had developed a fresh outflanking advance to overcome the check at Krivoi Rog in his first attempt to pinch out the Dnieper bend. Striking westward from the Kremenchug bridgehead this time, instead of southward, he penetrated almost to Kirovograd, but was then again checked. But this push, and a converging one from the Cherkassy bridgehead, had absorbed a considerable proportion of the meagre German reserves. Manstein was impaled on the horns of a dilemma. Forbidden by Hitler to take the long step-back that strategy suggested, he was bound to putty up these cracks in the stretch between the Dnieper bend and Kiev, even though this diminished his chances of keeping Vatutin confined within the Kiev salient. Inside that salient the Russian forces were mounting up like a dammed up flood.

Vatutin’s new offensive started on Christmas Eve, under cover of a thick early morning fog — like almost every successful attack in the later stages of the First World War. With that help it swamped the German positions on the first day, and, once it had burst out, spread so widely as to nullify countermeasures. Within a week it had regained Zhitomir and Korosten, and at the same time extended southward to lap round the previously untouched strongholds of Berdichev and Byelaya Tserkov.

On January 3, 1944, Russian mobile forces, driving westward, captured the junction of Novigrad Volynsk, fifty miles beyond Korosten. Next day they crossed the pre-war Polish frontier. On the southern flank Byelaya Tserkov and Berdichev were now abandoned by the Germans, who fell back towards Vinnitsa and the Bug — to cover the main lateral railway from Odessa to Warsaw. Here Manstein collected some reserves, and attempted another counterstroke, but it had little weight behind it, and Vatutin was well prepared to parry it. While it temporarily held up the Russian’s advance to the Bug, a check was only imposed here at the price of leaving the way clear for their flankwise spread. From Berdichev and Zhitomir they pushed westward, by-passing a block at Shepetovka, to capture the important Polish communications-centre of Rovno on February 5. On the same day a flanking drive captured Luck, nearly fifty miles north-west of Rovno and 100 miles beyond the Russian frontier.

More immediately damaging results were produced by the southerly spread of the flood. For here Vatutin’s left wing was converging with Koniev’s right wing to pinch off the German forces that had been kept, by Hitler’s rule of ‘no retreat’, in the strip between the Russians’ Kiev and Cherkassy bridgeheads. These forces, clinging to their forward position near the Dnieper, invited an encirclement that they were not permitted to evade. When the pincers dosed behind them on January 28, elements of six divisions were caught in the trap. Attempts to break through to them eventually succeeded, due to the efforts of the 3rd and 47th Panzer Corps. Of the 60,000 men in the Korsun pocket, 30,000 were extricated without their equipment and 18,000 were left as prisoners or wounded. Stemmermann, the commander of the 11th Corps, was among the killed.

The effort to release their trapped force had been at the cost of the position farther south, in the Dnieper bend. The Germans here were unable to check a stroke which Malinovsky delivered towards the baseline of their Nikopol salient. Nikopol had to be abandoned on February 8, and although most of the garrison managed to slip away the Germans had forfeited their long lease of that important source of manganese ore. They held on to Krivoi Rog for a fortnight longer, and then evacuated it under threat of a greater encirclement.

The deep bulges which the Russians had made in the southern front, between the Pripet Marshes and the Black Sea, had extended the frontage that the Germans needed to cover, while Hitler’s rigid principle had barred any timely step back to shorten the front by straightening it. The increasing toll of losses, especially in the Korsun coup, left gaps they were now powerless to cement. The price of Hitler’s principle was thus a much bigger retreat than would have been required two months earlier.

Weakness and the wide spaces produced a feeling of helplessness among the German troops; this feeling was deepened not only by the size of the advancing host but by its apparent immunity from supply problems. It rolled on like a flood, or a nomadic horde. The Russians could live where any Western army would have starved, and continue advancing when any other would have been sitting down to wait for the destroyed communications to be rebuilt. German mobile forces that tried to put a brake on the advance by raiding the Russian communications rarely found any supply columns at which to strike. Their impression was epitomised by one of the boldest of the raiding commanders, Manteuffel:

The advance of a Russian Army is something that Westerners can’t imagine. Behind the tank spearheads rolls on a vast horde, largely mounted on horses. The soldier carries a sack on his back, with dry crusts of bread and raw vegetables collected on the march from the fields and villages. The horses eat the straw from the house roofs — they get very little else. The Russians are accustomed to carry on for as long as three weeks in this primitive way, when advancing.*

* Liddell Hart:

The Other Side of the Hill,

p. 339.

The chances of stemming the tide were diminished by the dismissal of Manstein, who was suffering from eye trouble. While that was the immediate reason, it was expedited by friction with Hitler, whose strategy Manstein described as making no sense, and with whom he had argued in terms that the Fuhrer could not stomach. Henceforth the man who was regarded by German soldiers as their best strategist was left on the shelf. Although his sight was restored by an operation, he was only able to use it to follow on the map, in his aptly named place of retirement at Celle, the German Army being led blindly to the abyss.

The beginning of March 1944 saw a new combined manoeuvre, of still wider sweep, in development. Attention was at first focused by a thrust, near the headwaters of the Bug, into the south-eastern corner of Galicia. This was delivered by Marshal Zhukov, who had taken command of the armies west of Kiev in place of Vatutin, when the latter was ambushed and fatally wounded by anti-Soviet partisans. Striking from Shepetovka, Zhukov’s forces penetrated thirty miles in a day, and on the 7th were astride the Odessa-Warsaw lateral railway near Tarnopol. This thrust outflanked the defensive line of the Bug before the Germans could fall back to occupy it.

On the other flank of the southern front, Malinovsky was already exploiting the untenable position occupied by the Germans in the lower part of the Dnieper bend — utilising his newly gained positions near Nikopol and Krivoi Rog to start a scissors-movement. On March 13 he captured the port of Khersen at the mouth of the Dnieper, and cornered part of the German forces in this area. Meanwhile his converging sweep from the north was approaching Nikolayev, at the mouth of the Bug — although the resistance here was so stubborn that the place was not captured until the 28th. Long before then, a more dramatic development on the central stretch, between the sectors of Zhukov and Malinovsky, overshadowed the advances achieved by both.

Masked by these two horns, Koniev had struck from the direction of Uman and reached the Bug on March 12. Crossings were quickly secured. Losing no time, his armoured forces pressed on towards the Dniester, which in this area was only seventy miles beyond the Bug. Now that the ice was melting, the Dniester, with its fast-flowing stream and steep cliffs, looked a strong line for a stand. But there was no strength available, on the German side, for its defence. The Russian armoured forces reached its banks on the 18th and crossed the river on the heels of the retreating army — over pontoon-bridges at Yampol and neighbouring places. That easy passage was the sequel to their swift advance and their opponents’ confusion. Here again, much was due to the way that the Russian armoured forces, under General Rotmistrov’s direction, baffled opposition by the new tactics of moving widely deployed, thus nullifying the enemy’s attempt to check them by holding keypoints on the main lines of approach.

Any risk to this deep-driven wedge was lessened by a fresh stroke of Zhukov’s left wing southward from Tarnopol. This stroke was well timed in delivery, coming immediately after the Germans’ counterattacks near Tarnopol had been foiled by the Russians’ quick-knit defence, and in such a way as to exploit the Germans’ recoil. It was so aimed as to converge with Koniev’s thrust. After a rapid advance to the line of the Dniester, Zhukov’s left wing turned down the east bank, rolling up the enemy’s flank, and squeezing them in as it closed in towards Koniev’s right wing. Such combined and compound leverage carried both a defensive insurance and an extended offensive prospect.

While these flankwise sweeps were widening the breach, and cutting off portions of the opposing army that had started to retreat too late, the Russians were continuing the westward thrusts. Before the end of March, Koniev’s spearheads had penetrated to the line of the Prut near Jassy, and Zhukov’s had captured the important centres of Kolomyja and Cernauti — where they had forced the crossings of the upper Prut. This advance brought them close to the foothills of the Carpathians, the ramparts of Hungary.

In immediate reaction to this threat, the Germans occupied Hungary. It was obvious that this step was taken in order to secure the mountain-line of the Carpathians. They needed to maintain this barrier, not only to check a Russian irruption into the Central European plains, but as the pivot of any continued defence of the Balkans, The Carpathians, prolonged southward by the Transylvanian Alps, constitute a line of defence of great natural strength. Its apparent length is diminished, in strategical measurement, by the small number of the passes across it — thus facilitating economy of force. Between the Black Sea and the corner of the mountains near Focsani there is a flat stretch of 120 miles, but the eastern half of this is filled by the Danube delta and a chain of lakes, so that the ‘danger area’ was reduced to the sixty-mile Galatz Gap.

Early in April it looked as if the Germans would soon have to fall back on this rearward line, which was already endangered at the north-eastern corner by the wedge that Zhukov was driving between Tarnopol and Cernauti, towards the Yablonica Pass — more famous as the Tartar Pass. It seemed that Zhukov was going to repeat the torrential descent on Budapest of Sabutai who, leading Jenghiz Khan’s Mongols — the forerunners of modern armoured forces — had swept through the Hungarian Plain from the Carpathians to the Danube, in March 1241, covering 180 miles in three days.

On April 1 Zhukov’s spearhead reached the entrance to the Tartar Pass. The mountain-barrier is here a much lower and shallower obstacle than farther south, and the height of this pass is only 2,000 feet. Even such an easy climb can form a difficult defile if it is stubbornly defended — because the manoeuvring power of the attacker is cramped. So it proved here. The spearhead failed to penetrate, and there was not sufficient weight behind it to renew the momentum, as supplies could not keep up with such a prolonged advance.