History of the Second World War (88 page)

Read History of the Second World War Online

Authors: Basil Henry Liddell Hart

Tags: #History, #Military, #General, #Other

Thus Rabaul, with its garrison of more than 100,000 Japanese, was now isolated — and likewise left to ‘wither on the vine’. The barrier presented by the Bismarcks had been effectively pierced, with much less loss than would have been incurred in a direct attack.

In Bougainville Island nearly four months passed after the landings before the Japanese commander belatedly came to realise that the American landings on the west coast were their main ones. In March 1944 he brought a force of about 15,000 up there through the jungle and attacked the American beachhead, now held by over 60,000 men. He had estimated the American strength as about 20,000 troops and 10,000 aircraft ground crews — a figure which, even as an estimated total, ought to have made him see that his belated counterattack had a poor chance. In his abortive 1 to 4 assault, starting on March 8 and continued for two weeks, he suffered the loss of over 8,000 — more than half his force — while the American loss was less than 300. After this shattering repulse, what remained of the Japanese garrison, now hopelessly isolated, was also left to wither.

THE CENTRAL PACIFIC ADVANCE

This thrust, like the one through the South-west Pacific, was directed towards the Philippines, and the recovery of America’s position there — not direct towards Japan herself. At this stage of the war, the basic idea of the Joint Chiefs of Staff in Washington was that after reconquering the Philippines the American forces would move on to China and there establish large air bases from which the American air force could dominate the sky over Japan and pulverise her power of resistance, as well as cutting off her supplies.

This strategic plan was an underlying factor in American efforts to help the Chinese Nationalists under Chiang Kai-Shek, and sustain their resistance to the Japanese. Likewise it explained American anxiety to see the British resume their advance in Burma and re-open the Burma Road into southern China, so as to send war supplies to Chiang Kai-Shek and give him armed reinforcement.

In the event, the central Pacific advance proceeded so rapidly that Admiral Nimitz’s forces were led to switch their line of operation northward, and seize the Mariana Islands, while the development of the new long-range B.29 Superfortress bombers made it possible to strike direct at Japan, for the Marianas were less than 1,400 miles from the Japanese mainland. Moreover by the time the Marianas were captured, in October 1944, it had become clear to the American Chiefs of Staff that there was little prospect of Chinese Nationalist help, or of the British reaching southern China, in the near future.

THE CAPTURE OF THE GILBERT ISLANDS

In settling the plan of a central Pacific advance, Admiral King had wanted to start with a thrust at the Marshall Islands, but this idea was discarded for the lack of shipping and of trained troops needed to ensure success. Instead, it was decided to begin by a stroke at the Gilbert Islands, although they were a little farther from America’s Hawaiian base at Pearl Harbor, as their capture seemed a less exacting task while it would provide practice in amphibious operations and bomber bases for a subsequent attack on the Marshall Islands. In the Gilberts, the two most westerly islands, Makin and Tarawa, were to be the main objectives.

Nimitz, as overall C.-in-C., chose Vice-Admiral Raymond Spruance to command the attacking force. The ground troops, called the 5th Amphibious Corps, were under Major-General Holland Smith of the Marines, while the force that conveyed the troops was put in charge of Rear-Admiral Richard Turner, who had already acquired much experience of such operations in the Solomons. The whole was divided into two attack forces, a northern one to take Makin, with six transports carrying about 7,000 troops of the 27th Division, and a southern one to take Tarawa, with sixteen transports carrying the 2nd Marine Division of over 18,000 men. Besides escort carriers with the transports, the invasion was covered by Rear-Admiral Charles Pownall’s Fast Carrier Force, comprising six fleet carriers, five light carriers, and six new battleships, as well as smaller warships. In addition to 850 aircraft in the carriers, there were 150 land-based (Army) bombers.

The most important development here employed was the mobile Service Force to maintain the fleet in operations, and meet all its needs except for major repairs to the larger warships. It had tankers, tenders, tugs, minesweepers, barges, lighters, ammunition ships. Later, hospital ships, barrack ships, a floating dry-dock, floating cranes, survey ships, pontoon assembly ships and others were added. This floating ‘train’ greatly increased the range and power of the Navy in amphibious operations.

After preliminary bombing, the attack on the Gilberts, codenamed ‘Operation Galvanic’, began on November 20, 1943 — which happened to be the anniversary of the epoch-making offensive with massed tanks at Cambrai in 1917. The Gilberts were very weakly defended, as reinforcements promised under Japan’s ‘New Operational Policy’ of September had not yet arrived. On Makin, there was a garrison of only 800, and on the atoll of Apamama, a subsidiary objective, only twenty-five. But Tarawa had a garrison of over 3,000 and was strongly fortified.

At Makin, the small garrison held out for four days against a U.S. Army division, which was handicapped by inexperience. Far more effective was the action of a few ‘amphtracks’ (amphibious tracked vehicles that surmount coral reefs), but the landing force had only a few of these new vehicles.

Tarawa, much more strongly defended and fortified, was given a heavy naval bombardment (3,000 tons of shells in 2½ hours) as well as massive air bombing before being attacked by the 2nd Marine Division, which had distinguished itself at Guadalcanal. Even so, a third of the 5,000 landed on the first day were knocked out in crossing the 600-yard strip between the coral reef and the beaches. But the survivors were indomitable and forced the Japanese to withdraw to two interior strong-points, and that withdrawal enabled the Marines to spread over the island and hem in the defending strong-points. Then on the night of the 22nd the Japanese solved the Marines’ still difficult problem by switching over to repeated counterattacks, in which they were wiped out. After that the remaining islands were soon cleared.

The Navy lost an escort carrier, but on the whole the carrier groups proved that they could beat off Japanese air attacks both by day and night, while the Japanese surface warships did not challenge Admiral Spruance’s large fleet.

The American people were shocked by the losses suffered, and the attack on the Gilberts became a source of violent controversy. But the experience gained proved valuable in many detailed respects, and led to important improvements in the technique of amphibious operations. Rear-Admiral S. E. Morison, the official Naval historian, called it ‘the seed bed of victory in 1945’.

Nimitz and his staff were already busy in planning the next bound, to the Marshalls, but it was only after the attack on the Gilberts that a key change was made in the plan, at Nimitz’s insistence. Instead of a direct attack on the nearest, most easterly, islands in the group, they were to be by-passed, and the next leap made to Kwajalein atoll, 400 miles farther on. After that, if all went well, Spruance’s reserve would be sent on to seize Eniwetok, at the far end of this 700-mile chain of islands. The command was organised similarly to that for the attack on the Gilberts, but two fresh divisions were employed for the assault, which totalled 54,000 assault troops as well as 31,000 garrison troops to occupy the conquered territory. On the naval side, there were four carrier groups, which included twelve carriers and eight battleships. Many more ‘amphtracks’ were used, and these were both armed and armoured, while fighter aircraft and gunboats were equipped with rockets. The preparatory bombardment was to be four times as great as the attack on the Gilberts.

The success of the plan was helped by the way that the Japanese sent such reinforcements as they could provide to the easterly islands of the group, thus being caught unawares by the remodelled American strategy — of indirect approach and by-passing moves.

After a brief return to Pearl Harbor for a rest and refit, the fast carrier forces came back at the end of January 1944, and by sustained sorties (over 6,000 in all) paralysed Japanese air and sea movements throughout the attack on the Marshalls — while destroying some 150 Japanese aircraft.

The first move in the attacks was the capture on January 31 of the undefended island of Majuro, in the easterly chain, which provided a good anchorage for the Americans’ supporting Service Force. Then the small islands flanking Kwajalein were captured, and the main attack promptly followed on February 1. The garrison assisted the process of overcoming it by repeated suicidal counterattacks, charging in the wild and sacrificial ‘Banzai’ spirit. Although the Japanese garrison had totalled over 8,000 men, of whom some 5,000 were combat troops, only 370 Americans were killed in achieving this victory.

As the Corps reserve (of some 10,000 men) had not been called on, it was sent on to seize Eniwetok. There the Americans would be still a thousand miles short of the Marianas, while less than 700 miles from Truk, the major Japanese base in the Carolines. So as a flank safeguard to the move against Eniwetok a heavy raid on Truk was delivered from nine of the American carriers on the same day as the Eniwetok landings. A further stroke was delivered that night, with the aid of radar to identify the targets, and a third the next morning. Although Admiral Koga had prudently withdrawn most of his Combined Fleet, two cruisers and four destroyers were sunk, as well as twenty-six tankers and freighters. In the air the Japanese suffered much worse, losing over 250 planes, for an American loss of twenty-five. The strategic effects were even more striking, as this shattering triple raid caused the Japanese to withdraw all aircraft from the Bismarcks, leaving Rabaul helpless — thus proving that the central Pacific advance could assist, and not retard, MacArthur’s progress in the South-west Pacific.

Above all, the operation showed that carrier forces could cripple a major enemy base without occupying it, and without the help of land-based aircraft.

In these circumstances, the capture of Eniwetok proved easy. The surrounding islands were quickly taken, and even the garrison of the main island was overcome in three days, by a landing force of less than half a division’s strength. The building of new airfields in the Marshalls, for American use, then proceeded fast. The Gilberts and the Marshalls had been gained in only just over two months, whereas the Japanese had hoped that this delaying zone could be held for six months, and the key position of Truk in their ‘absolute’, or essential, barrier zone had been badly impaired.

BURMA, 1943-1944

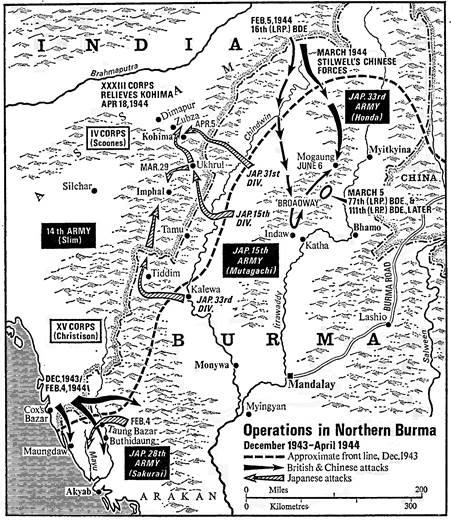

The season’s campaign in Burma ran a very different course from expectation, and formed a depressing contrast to the now rapid Allied advance in the Pacific, especially the central Pacific. For the main feature of the war in Burma was another Japanese offensive — and the only one in the war that saw the Japanese cross the Indian frontier, into southern Assam — whereas the British had been counting on, and planning, an offensive that would clear the invaders out of northern Burma and open the road to China. The great improvement in communications from India, and the growing strength of their forces, had appeared to offer a good prospect.

The Japanese attack was aimed to forestall and dislocate the British offensive, and it came uncomfortably close to tactical success, despite inferior strength, while even its eventual failure had the strategical effect of postponing the British advance until 1945. But once it was foiled, in the spring of 1944, by the tough defence of Imphal and Kohima, both thirty miles inside the Assam border, it soon became evident that the Japanese had exhausted so much of their scanty strength in this last offensive effort that they could offer no strong resistance to the immediate British counter-offensive, nor to the larger scale British offensive that followed in 1945.

In preparation for the campaign the Allies had agreed among themselves that the reoccupation of northern Burma was to be the primary objective, as the shortest way to renew direct touch with China and resume supplies to her over ‘the Burma Road’ across the mountain barrier. After prolonged discussion, other schemes were put aside — such as amphibious operations against Akyab, Rangoon, or Sumatra. The British offensive in northern Burma was to be preceded by a renewed attack in Arakan, and a diversionary attack by the Chindits in the north.

At the end of August 1943 a new and unified ‘South-East Asia Command’ was set up under Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten, previously Chief of Combined Operations. The respective Service heads under him were Admiral Somerville, General Giffard, and Air Chief Marshal Peirse, while General Stilwell, the American, was to be Deputy ‘Supremo’ to Mountbatten. The India Command was separated from S.E.A.C., and made responsible for training as distinct from operations; Wavell was ‘pushed upstairs’ to become Viceroy of India and Auchinleck appointed to succeed him as C.-in-C. India.