History of the Second World War (64 page)

Read History of the Second World War Online

Authors: Basil Henry Liddell Hart

Tags: #History, #Military, #General, #Other

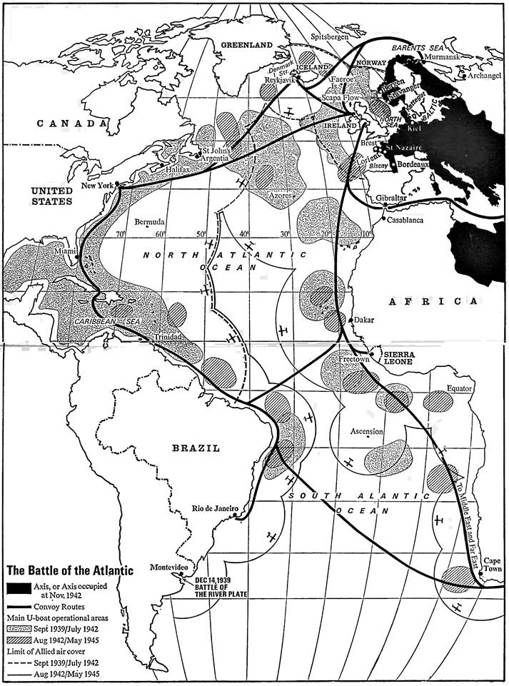

CHAPTER 24 - THE BATTLE OF THE ATLANTIC

The most critical period in the Battle of the Atlantic was during the second half of 1942 and the first half of 1943, but its long and fluctuating course was co-existent with the whole six years’ course of the war. Indeed, it can be said to have started before the war itself, as the first ocean-going U-boats sailed from Germany to their war stations in the Atlantic on August 19, 1939. By the end of that month, on the eve of the German invasion of Poland, seventeen were out in the Atlantic, while some fourteen coastal-type U-boats were out in the North Sea.

Despite their late start in rearming themselves with submarines, the Germans had a total strength of fifty-six (although ten were not fully operational) on the outbreak of war, which was only one less than that of the British Navy, Of these, thirty were ‘North Sea Ducks’, unsuitable for the Atlantic.

The first score achieved was the sinking of the outward-bound liner

Athenia

on the evening of September 3, the same day that Britain declared war, two days after the German invasion of Poland. It was actually torpedoed without warning, contrary to Hitlers specific order that submarine warfare was to be conducted only in accordance with the Hague Conventions; the U-boat commander justified his action by asserting his belief that the liner was an armed merchant cruiser. During the next few days several more ships were sunk.

Then on the 17th a more important success was gained when the aircraft-carrier

Courageous

was sunk by

U.29

off the Western Approaches to the British Isles. Three days earlier the aircraft-carrier

Ark Royal

had had a narrow escape from

U.39

— which, however, was promptly counterattacked and sunk by the escorting destroyers. The manifest risks led to the fleet aircraft-carriers being withdrawn from submarine-hunting.

U-boat attacks against merchant-shipping also had considerable success. A total of forty-one Allied and neutral ships, amounting to 154,000 tons, were sunk in the opening month, September, and by the end of the year the losses reached 114 ships, and over 420,000 tons. Moreover in mid-October the

U. 47

under Lieutenant Prien had penetrated the fleet anchorage at Scapa Flow and sunk the battleship

Royal Oak,

causing the temporary abandonment of this main base until the defences were improved.

It is significant, however, that in November and December, merchant shipping losses were less than half what they had been the first two months, and more shipping had been lost to mines than to U-boats. Moreover, nine U-boats had been sunk — a sixth of the total strength. Air attacks on shipping had been a nuisance, but no worse.

During this early part of the war, the German Navy placed great hopes in its surface warships, and not only in its U-boats, but such hopes were not borne out by experience. On the outbreak of war the pocket-battleship

Admiral Graf Spee

was in position in mid-Atlantic, and her sister-ship

Deutschland

(later renamed

Lutzow

) in the North Atlantic — although Hitler did not allow them to start attacks on British shipping until September 26. Neither of them achieved much — and the

Graf Spee,

cornered in the mouth of the River Plate, was driven to scuttle herself in December. The new battle-cruisers

Gneisenau

and

Scharnhorst

made a brief sortie in November, but after sinking an armed merchant cruiser in the Iceland-Faeroes channel bolted for home. Allied ships were already sailing in convoy, after their experience in 1917-18, and although escorts were inadequate — and all too many ships still had none — they proved a remarkably effective deterrent.

After the fall of France in June 1940 the danger to Britain’s shipping routes became much more severe. All ships passing south of Ireland were now exposed to German submarine, surface, and air attack. Except at great hazard, the only remaining route in and out was round the north of Ireland — the North-Western Approaches. Even that route could be reached, reported on, and bombed by the first of the German long-range aircraft, the four-engined Focke-Wulf ‘Kondor’ (the F.W. 200), operating from Stavanger in Norway and Merignac near Bordeaux. In November 1940 these long-range bombers sank eighteen ships, of 66,000 tons. Moreover the U-boats’ toll had risen greatly — to a total sixty-three ships, amounting to over 350,000 tons, in the month of October.

The threat had become so serious that a large number of British warships were pulled back from anti-invasion duties and sent to the North-Western Approaches. Even so, surface and air escorts were perilously weak.

In June, the first month of the changed strategic situation, U-boat sinkings had bounded up to fifty-eight ships of 284,000 tons, and although falling a little in July, they averaged over 250,000 tons during the months that followed.

On the east coast route, minelaying by air had caused more damage than U-boats in the later months of 1939, and after the German invasion of Norway and the Low Countries in the spring of 1940 its menacing pressure was intensified.

Moreover in the autumn the pocket-battleship

Admiral Scheer

slipped out undetected into the North Atlantic, and on November 5 attacked a convoy homeward-bound from Halifax, Nova Scotia, sinking five merchant ships and the sole escort, the armed merchant cruiser

Jervis Bay

— which sacrificed herself in gaining time for the rest of the convoy to escape. The

Scheer

s sudden appearance on this vital convoy route temporarily disorganised the entire flow of shipping across the Atlantic, causing other convoys to be held up for two weeks, until it was known that the

Scheer

had gone on into the South Atlantic. Here she found fewer targets, but raised her toll to sixteen ships, of 99,000 tons, by the time she returned safely to Kiel on April 1 after a ‘cruise’ of over 46,000 miles. The cruiser

Admiral Hipper

also broke out into the Atlantic at the end of November, but at dawn on Christmas Day had a rude shock when she attacked a convoy which she soon found to be strongly escorted, as it was a troop convoy bound for the Middle East. The escorting cruisers drove off the

Hipper,

and trouble in her own machinery led her to make for Brest. From here in February she made a second sortie, and was somewhat more successful, sinking seven ships in an unescorted group steaming up the African coast, but her own fuel was running low and her captain thus decided to return to Brest. In mid-March the German Naval Staff ordered her to return home for a more thorough refit, and she got back to Kiel just before the

Scheer

. The

Hipper’s

low endurance had shown that, apart from mechanical defects, her type was not suited for commerce raiding.

Next to the U-boats and minelaying, the Germans’ most effective weapon in the war at sea proved to be disguised merchant ships converted for raiding purposes, which they had been sending out on long cruises since April 1940. By the end of that year the first ‘wave’ of six had sunk fifty-four merchantmen, totalling 366,000 tons — largely in distant seas. Their presence, or possible presence, caused as much worry and dislocation as the sinkings they achieved, while the threat was multiplied by the masterly way in which the Germans kept them refuelled and supplied at secret rendezvous. The raiders were skilfully handled and their targets well-chosen — only one of them had been brought to action, and that had escaped serious damage. Yet their captains, with one exception, had behaved humanely, allowing the crews of the ships attacked time to take to the boats, and treating their prisoners decently.

In face of the manifold threat, above all that of U-boats in the Atlantic approaches to Britain, the Royal Navy’s escort resources were heavily strained, and overstrained. From the French Atlantic ports — Brest, Lorient, and La Pallice near La Rochelle — U-boats were able to cruise as far as 25° West, whereas during the summer of 1940 the British could only provide escorts up to about 15° West, some 200 miles west of Ireland, and outward bound convoys then had to disperse, or steam on unescorted. Even in October, close escort was only extended to about 19° West — about 400 miles west of Ireland. Moreover, the usual escort was merely one armed merchant cruiser, and it was not until the end of the year that the average could be increased to two vessels. Only convoys to the Middle East were given more powerful protection.

Here it should be mentioned that Halifax in Nova Scotia was the main Western terminal for the Atlantic convoys, and that homeward-bound convoys — carrying supplies of food, oil, and munitions — were escorted by Canadian destroyers for the first 300-400 miles, after which the ocean escort took over, until the convoy reached the better-protected area of the Western Approaches.

Valuable aid towards meeting the escort problem came from the advent of the corvettes in the spring of 1940. These small vessels, of a mere 925 tons, were exhausting for the crews in rough weather, and suffered the handicap of not being fast enough to overtake, or even to keep up with, a U-boat on the surface, but they did most gallant work in escorting convoys in all weathers.

A larger aid came from the agreement which Churchill negotiated with President Roosevelt, in September, after two months’ persuasive efforts, whereby fifty of the U.S. Navy’s old and surplus destroyers from World War I were obtained in exchange for a ninety-nine year lease of eight British bases on the far side of the Atlantic. Although these destroyers were obsolescent, and had to be fitted with the Asdic submarine-detecting device before they could be brought into use, they were soon able to make an important contribution to the escort problem and the anti-submarine campaign. Moreover the double transfer enabled the United States to prepare bases for the protection of its own seabound and coastal shipping, while taking the first of the steps which involved that great neutral country in the Battle of the Atlantic.

The coming of winter, and bad weather, naturally brought an increase of the difficulties of convoy, and convoy escorts, but also a diminution of German submarine activity. By July 1940 German figures show that U-boat strength had been increased 50 per cent since the start of the war, that twenty-seven had been destroyed, and fifty-one remained. By the following February the effective total fell to twenty-one. But with the French bases the Germans could keep more U-boats at sea out of a reduced smaller total strength, and could also use their smaller coastal-type U-boats on the ocean routes.

On the other hand, the Italian Navy’s contribution to the struggle proved negligible. Although their submarines had begun to operate in the Atlantic from August on, and by November no less than twenty-six were out on the ocean, they achieved virtually nothing.

Although the pressure of the U-boat campaign diminished during the winter, mainly due to bad weather, it was renewed early in 1941, and at the same time multiplied by Admiral Donitz’s introduction of ‘wolf-pack’ tactics — by several U-boats working together, instead of individually. These new tactics had been introduced in October 1940, and were developed in the months that followed.

The way they operated was that, when the existence of a convoy had been approximately established, U-boat Command H.Q. ashore would warn the nearest U-boat group, which would send a submarine to find and shadow the convoy and ‘home’ the others onto it by wireless. When they were assembled on the scene, they would launch night attacks on the surface, preferably up-wind of the convoy, and continue these for several nights. During daylight the U-boats would withdraw well clear of the convoy and its escort. Attacking on the surface, they had an advantage in speed over most of the escorts. Night surface attacks had been made in World War I, and Donitz himself had described in a book before the second war how he would do them.

These new tactics took the British unawares, as they had been thinking mainly of submerged attack, and pinned their faith to the Asdic device, the underwater detecting device, which had a range of about 1,500 yards. The Asdic could not detect U-boats that were operating on the surface like torpedo-boats near the convoy, and when these submarines were employed at night, escorts were virtually blindfolded. This German exploitation of the value of night attacks by surfaced U-boats thus nullified the British preparation for submarine warfare, and threw it off balance.

The best chance of countering the new tactics lay in early location of the shadowing U-boat, the ‘contact-keeper’, and driving it away. If the escort could make the U-boats dive, these would be handicapped, their periscopes being useless at night. A very important countermeasure to night attacks was the illumination of the sea. At first this was dependent on star-shell and rocket flares, but these were superseded by a more efficient illuminant known as ‘snowflake’, which went far towards turning darkness into daylight, while a powerful searchlight, called the Leigh Light after its inventor, was fitted in aircraft that were employed in convoy escorts and anti-submarine patrols. Still more important was the development of radar to supplement visual sighting. Along with new instrumental devices came more thorough training for escort vessels and escort groups and a marked improvement in the intelligence organisation.