Read History Buff's Guide to the Presidents Online

Authors: Thomas R. Flagel

Tags: #Biographies & Memoirs, #Historical, #United States, #Leaders & Notable People, #Presidents & Heads of State, #U.S. Presidents, #History, #Americas, #Historical Study & Educational Resources, #Reference, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #Political Science, #History & Theory, #Executive Branch, #Encyclopedias & Subject Guides, #Historical Study, #Federal Government

History Buff's Guide to the Presidents (41 page)

These missiles were hardly a mystery to Soviet intelligence. The dilemma for Moscow was having no viable equivalent. For all intents and purposes, the United States was out of range, and the only possible launch pad was the pro-Soviet island of Cuba. Accordingly, and without much foresight, Moscow shipped sixteen SS-4 medium-range nuclear missiles to Cuba in the summer of 1962. Twenty more were on the way, each capable of hitting Dallas or Washington, D.C. Also en route were sixteen SS-5 intermediates, all of which could strike any of the contiguous forty-eight states.

41

On October 14, a U.S. spy plane photographed suspicious construction and equipment in the jungles of Cuba. Two days later, the Kennedy administration viewed the confirmed images of SS-4 missiles under assembly. If allowed to become operational, the rockets could hit the very city in which they were standing. The options were to bomb the sites, invade, or do nothing. The Joint Chiefs advised invasion. The president chose a fourth option, endorsed by Defense Secretary Robert McNamara and Attorney General Robert Kennedy. The U.S. Navy would stage a “quarantine” of incoming ships to Cuba (to call it a “blockade” was technically an act of war).

From that point onward, any number of events could have resulted in a rapid, catastrophic escalation. Communications were slow, sometimes taking hours for messages to be sent and received through antiquated means. Most ships respected the quarantine, but not all. A Soviet attack sub was discovered a few miles from the Florida coast. At least sixteen SS-4s went on line. Ten days into the standoff, a U-2 plane was shot down. Kennedy himself began to see invasion as his only option but allowed secret negotiations more time. Along with the missiles, the Soviets were also sending cruisers, destroyers, tanks, infantry regiments, artillery brigades, MIG fighters, nuclear bombers, and nuclear submarines. McNamara personally wondered if he would be alive the following week.

42

To their credit, both Kennedy and Khrushchev eventually realized that the situation was largely a crisis of their own making, and on October 28, they readily accepted the first opportunity to resolve the situation. In exchange of U.S. pledges to end the quarantine, remove its fifteen missiles in Turkey, and never invade Cuba, the Soviets would remove all missiles and personnel from the island. Perhaps greater than the solution itself was the immediacy with which it was announced, virtually eliminating the risk of accident or rogue aggression from either side.

As with most diplomatic solutions, this de-escalation had its critics. Even after the worst had passed, there were military figures in Cuba, the Soviet Union, and the United States calling for offensive operations. The withdrawal was a key reason for Khrushchev’s downfall two years later, and Kennedy’s pledge on Cuba made him look “soft on communism.” But in their careful resistance to armed aggression, Kennedy and Khrushchev spared at least several thousand lives and at best prevented a possible war of global proportions.

43

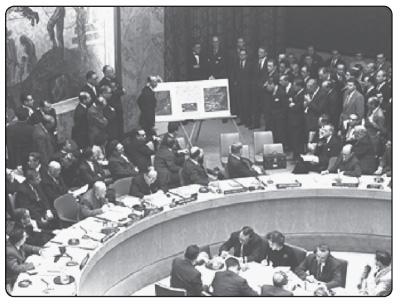

To support U.S. claims, Ambassador Adlai E. Stevenson presented photographic evidence of ballistic missile installations in Cuba to the UN Security Council.

During the Cuban Missile Crisis, the U.S. Armed Forces went on DEFCON 2, the second-highest level of Defense Readiness Condition, for the first and only time during the Cold War. DEFCON 1 authorizes the use of nuclear weapons.

7

. RICHARD NIXON’S “JOURNEY FOR PEACE”

COMMUNIST CHINA (FEBRUARY 21–28, 1972)

Nixon equated domestic programs with “building outhouses in Peoria,” but he loved the intrigue of global affairs. Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, Adm. Thomas Moorer observed, “Once the president was very involved with W

ATERGATE

, he would sit at the NSC meetings apparently in heavy thought until someone mentioned foreign policy, and it was just like giving him a needle; he would spark right up.”

44

President and Mrs. Nixon mug for the cameras on the Ba Da Ling section of the Great Wall. While public events included several banquets, cultural exhibitions, and a tour of the Forbidden City, secret meetings covered hypersensitive subjects such as Taiwan and Vietnam.

His biggest hit came when he bridged the chasm between the United States and the most populous nation on earth, two countries that had been thoroughly estranged from one another for more than twenty years. To Americans, China was the great “lost” world, the stalwart ally against Japan in World War II, stolen away by communists in 1949. Mao Zedong’s brutal Cultural Revolution of the late 1960s only cemented the specter of a ruthless system. To the Chinese, the United States was the worst of all enemies, an imperial power perched and ready to strike the People’s Republic from bases in Okinawa, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan. The United States was already bombing the living daylights out of Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam.

45

But China and America had a common foe in the Soviet Union, whom they both suspected of wanting to take over the world. For more than two years, Nixon quietly investigated whether Red China might be open to a bilateral meeting. In secret negotiations conducted through Pakistan and Romania, the desired answer finally arrived in early 1971—Nixon was welcome to visit Peking (Beijing).

46

News of his impending trip stunned the American public. No sitting president had ever visited China. But many quickly reasoned that only an anticommunist could politically make such a move, and most were supportive of the trip. Like their president, the public was curious but cautious. Plans were finalized for February 1972, and upon his departure, Nixon said he hoped the trip would become a “journey for peace.”

47

The weeklong agenda was feverishly eager—lavish dinners, theater productions, a tour of the Great Wall, and most significantly, several high-level meetings. Nixon met with the aging and sickly Mao Zedong shortly after he arrived. It was to be their only encounter during the trip. They spoke for about an hour, spending most of the time complimenting each other and belittling themselves.

The pivotal discussions were with Premier Zhou Enlai. Topics ranged from Sino-Indian relations to the status of Korean War POWs. Both sides were thoroughly grateful for the experience, but they were unwilling and unable to make any major commitments. On Vietnam, Zhou hinted that China would never militarily intervene, but he refused to mediate a peace between North and South. Concerning Taiwan, Nixon expressed a belief that there should be “one China,” but he was vague on whether it should be nationalist or communist. They mentioned the possibility of normalized relations, but full diplomatic recognition would not come for several years.

48

The journey was a triumph nonetheless. The United States began to allow open travel to mainland China, and rudimentary trade agreements followed. The Soviet Union, fearing a Sino-American alliance, warmed to the idea of détente and invited Nixon to Moscow. By 1979, Beijing and Washington were exchanging ambassadors.

Nixon’s China trip led to the creation of a U.S. Liaison Office in Beijing. In 1973, David Bruce became the first American emissary to the People’s Republic. He was succeeded the following year by George H. W. Bush.

8

. JIMMY CARTER TAMES A BLOODFEUD

CAMP DAVID ACCORDS (SEPTEMBER 5–17, 1978)

The Arab-Israeli War of 1948, the Suez Crisis in 1956, the Six-Day War of 1967, the War of Attrition from 1967 to 1970, the Yom Kippur War in 1973—those who claimed Israel was a stabilizing element in the Middle East were not checking the scoreboard. Many American presidents tried to establish some semblance of lasting peace between any Arab state and the Jewish homeland. None succeeded until Jimmy Carter all but forced it upon Egypt and Israel in the autumn of 1978.

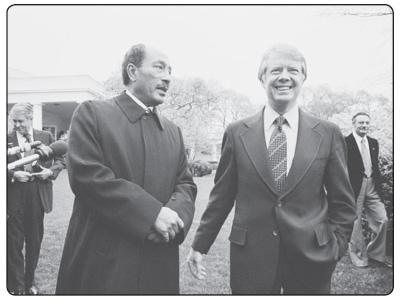

Carter’s initial plan was to invite Egyptian president Anwar Sadat and Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin to Camp David for calm discussions on Palestine, mutual diplomatic recognition, and a possible peace treaty. The optimistic Democrat was working on a number of false assumptions, primarily that such painful and divisive topics could ever be calmly discussed between Israel and its most powerful enemy. He also believed his close friendship with Sadat would encourage Begin to be more cooperative. Plus, the placid woodland setting was supposed to put both parties at ease.

49

As the three first sat down, it was immediately clear that Carter had guessed wrong on everything. Sadat and Begin despised each other on a personal level. The Egyptian leader worsened the situation by demanding that Israel surrender all occupied lands in Gaza and the West Bank, pay reparations for past wars, and compensate refugees for their lost homes. Begin calmly informed both gentlemen that he had no desire to agree to anything, and he abruptly retired to his cabin.

50

After two days and no progress, Carter started meeting with each side separately and invited Secretary of State Cyrus Vance to try his hand with other officials in attendance. A week passed, and Sadat eased his stance on Palestine, asking instead for Israeli withdrawal from the Sinai Peninsula. Nothing was achieved, and the camp’s total isolation began to wear on the visitors. Sadat and his staff were packing their bags, threatening to leave, when Carter finally lost his temper.

The former naval officer warned his friend that leaving would do more than end their friendship; it would mean the end of U.S.–Egyptian relations. Carter then proceeded to threaten Begin. If the prime minister did not agree to some meaningful breakthrough, Carter would tell the world media how Israel sabotaged the entire summit by refusing to negotiate. The tantrum worked.

51

Carter threatened his old friend Anwar Sadat to either cooperate with Israel or lose all American support for the foreseeable future.

In return for U.S. assistance in building new airfields, Israel agreed to withdraw from the Sinai, and the adversaries pledged to sign a peace treaty with each other. The following year, they fulfilled that promise.

Though both Sadat and Begin were roundly criticized by their own people for capitulating too much to a longtime enemy, their relations with the United States stabilized thereafter, and the two nations have not directly fought each other ever since.

52

In spite of their obstinate behavior at Camp David, both Anwar Sadat and Menachem Begin were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1978.

9

. RONALD REAGAN’S BEST FAILURE

REYKJAVÍK SUMMIT (OCTOBER 11–12, 1986)