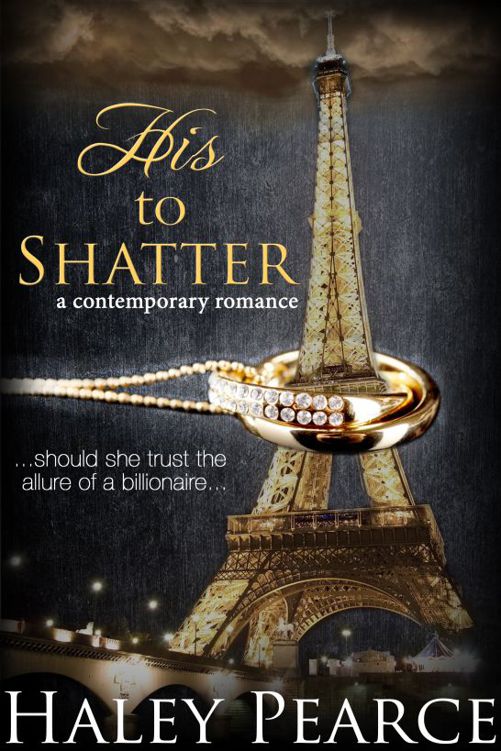

His To Shatter

Authors: Haley Pearce

Tags: #coming of age romance, #billionaire sex, #like shades, #contemporary erotic romance, #marriage of convenience, #billionaire romance, #Contemporary Romance

A Contemporary Romance

By

Haley Pearce

SMASHWORDS EDITION

* * * * *

PUBLISHED BY:

Infinite Muse Press on Smashwords

His To Shatter: A Contemporary Romance

Copyright © 2013 by Haley Pearce

This book is a work of fiction and any

resemblance to persons, living or dead, or places, events or

locales is purely coincidental. The characters are productions of

the author’s imagination and used fictitiously.

Adult Reading Material

The material in this document contains

explicit sexual content that is intended for mature audiences only

and is inappropriate for readers under 18 years of age.

* * * * *

A Contemporary Romance

* * * * *

CONTENTS

* * * * *

Acknowledgements

* * * * *

First I would like to thank

my readers, above all, the very reason that I began writing was to

share my ideas with all of you.

His To

Shatter

is a novel that is very dear to my

heart, many of the characters are inspired by real people who I

have had the pleasure or displeasure of knowing throughout my

life.

The story of Madison's troubled upbringing

is in many ways a confession, it's my first and only real

expression of the complicated feelings that I harbor as a result of

growing up as an "adult child" of alcoholic and codependent

parents.

My heart sincerely goes out

to anyone who can relate to Madison's character in any way, this

story was written for you.

His To

Shatter

is about the triumph of the human

spirit, the realized ambitions of a girl from a bad place who

chooses to rise above her surroundings instead of wallowing in

them.

Most of all, this story is about how we

can't do anything alone in this world, nothing worth doing at

least. We all need to eventually open ourselves and trust in other

people who have earned it. We deserve success, we deserve nice

things, we deserve happiness.

* * * * *

Chapter One

* * * * *

I had already been awake for hours when the

sky began to lighten over the East River. Since moving to New York

City a year earlier, I’d fallen in love with the River Park,

especially at sunrise. Every morning, without fail, I rolled out of

bed at six o’clock, threw on my years-old running shoes, and hit

the pavement. While the rest of the Lower East Side of Manhattan

slumbered peacefully behind the closed doors of their fifth story

walkups, their penthouses, their lofts, I tore silently through the

streets. I never wore headphones while I ran through the city,

preferring the tentative silence that overtook the streets so early

in the morning. The daily hour I reserved for running was a time of

mediation, of calming; and I would need them both in spades that

day.

As I bore down on the Brooklyn Bridge,

keeping my quick but steady pace, I ran through my pitch speech for

the eighteen thousandth time. Later that day, my big interview was

finally going to happen. After a year of inquiry emails, follow-up

phone calls, and preliminary meetings, I was actually going to have

an interview with the employer of my dreams, the international

marketing firm Corelli. Just thinking the name sent shudders of

anticipation running through my already keyed-up body.

Corelli

, I thought to myself again and again, making a

mantra of the name. Ever since I’d decided to focus on

international marketing as a wide-eyed undergrad, Corelli had been

the shining beacon that I had aspired to. Now, it was actually

within my reach—and I was positively beside myself with nerves.

I slowed my pace to a walk at the end of the

first leg of my run. My roommates often made fun of me for running

my daily six miles, but that time was entirely essential to my

happiness. As I slung my leg over the back of a park bench,

stretching out my calves and quads, I breathed in the light April

air with relish. I hadn’t been prepared for how brutal New York

City winters could be, but now the cold grip of that ghastly season

was loosening. Morning glories crept along the chain link fences,

now, and tiny green sprouts popped up among the bricks. Even in New

York, spring was beginning to show its face. And after spring had

blossomed into summer, I could very well be headed to Paris for the

internship I’d been lusting over for years.

Interning at Corelli that summer was, as

childish as it may sound, my dream. I had been lucky enough to get

into the international marketing graduate program at NYU after a

somewhat fraught undergraduate career. Living in the city as a full

time student let me focus all my energy on reinventing myself. I

felt like I could finally find the resolve to put my past to rest

as an unfortunate prelude to my real life, my life as a big-time

marketing executive. And Corelli was the cornerstone of that

fantasy.

A low groan escaped my lips as I leaned

deeply into my stretch. Few things satisfied me more in life than

that sweet, slightly painful feeling. I looked out over the East

River as I switched legs, squinting across the water toward

Brooklyn. Along both shore lines, piles of driftwood and detritus

stood out like found art. The rugged mayhem of the water’s edge

contrasted the tall, gleaming, spotless skyline of Manhattan,

rising above me into the ever-lightening sky. New York was always a

beautiful city, whatever the time of day or night one wandered out

into its embrace. But sometimes, when I least expected it, the full

splendor of my new home would hit me square in the gut, its beauty

bringing real tears of joy and wonder to my eyes.

I let out a little laugh as I pulled myself

together. Leave it to me to cry over a sunrise. I turned on my heel

and started back toward my apartment. The rhythmic pounding of my

sneakers against the asphalt comforted me like nothing else could.

I’d been running for years, having discovered the healing powers of

a good long dash when I was still a skinny, awkward kid. I’d done

my growing up in West Chester, Pennsylvania—otherwise known as the

middle of nowhere, for someone like me. There had been very little

to do in my hometown once my friends and I outgrew trekking through

the wooded hills and hunting for salamanders in the streams. When

the kids I went to school with started entertaining themselves with

booze and weed, bouncing from basement to basement with no

motivation except getting high, I was left to my own devices. I

didn’t touch drugs and alcohol as a rule—not after what they’d done

to my once-happy family.

Bitterness rose within me the instant I let

my thoughts touch upon my family. I made a habit of leaving my

former home out of my mind; it was the only way I could get through

the day. When I left for college, I started the drawn-out process

of extricating myself from the wreckage of my home life. If I

concentrated very hard, I could remember a time when my family had

been intact, supportive, and even wholesome. But those memories

were nothing more than fleeting shapes and shadows; the years I

could actually remember were nothing but darkness, shame, and

grief.

Maybe growing up would have been easier, if

I’d had siblings. But it was just me and my parents, alone in our

little converted farm house in the low hills of Pennsylvania. My

parents had married young, after becoming unexpectedly pregnant

with me. My mother, Francie, had only been nineteen when I was

born; my father, Steve, had been twenty. Neither had gone to

college, but for a while it seemed as though they might do OK for

themselves anyway. Mom started working at a bank, once I was old

enough for day care, and Dad had a decent job at the local high

school, coaching one sport a season and teaching PE to boot.

The day that everything fell to pieces was

one that I knew I would remember forever. I was five years old, and

had just finished my first week of kindergarten. As soon as I

walked through the doors of my elementary school, I was hooked.

There were books, crafts, and other kids

everywhere

. That

first week of school had been a dream; flying across the monkey

bars at recess, trading my white milk for chocolate in the lunch

line, napping alongside my newfound friends in our cozy classroom.

For a brief, beautiful moment, I thought that life would be perfect

from then on out. I could never have known just how wrong that

thought was.

Dad was found out that week, at long last.

The police showed up at our house on Friday night and arrested him

for a slew of charges. As it happened, he’d been engaging in some

rather inappropriate behavior with his older students. Weekends

would often find him partying with the kids on his team, showing up

to basement gatherings like an overgrown teenager. One of his

students had finally come forward and alerted the authorities to

his behavior. Apparently, he was not shy about providing booze to

the kids he coached, nor was he resolute in keeping his hands off

the girls. My mother had cried for a full day after they took Dad

away, baffled by his actions. I had done my best to take care of

her as she rearranged our finances to bail Dad out. The one thing

she kept saying, over and over again, was “Your father is a good

man. Your father is a good man.”

But even then, I no longer believed that in

my heart.

The high school fired Dad without ceremony.

None of the girls he’d fooled around with were under eighteen, so

at least he didn’t have to add “pedophile” to the list of traits

people might assign him. But to me, from that time on, he was a

pervert—a desperate old man past his prime, delusional with false

power. And once he was let go from the school, those delusions and

aggressions only got worse. With no job to go to, Dad found a new

hobby: drinking incessantly. His descent into alcoholism wasn't

even surprising, it was just sad.

Worse still was the way that my mother

defended his pathetic behavior. Mom had always been insecure about

her relationship with Dad. He’d spent the better part of their

marriage accusing her of trapping him with a baby, of keeping him

penned up during the prime years of his life. And after being

blamed so many times, Mom really started to believe it. And so,

when Dad’s philandering came out into the open, she wasn’t even

angry with him. She believed wholeheartedly that it was her fault

he had strayed; she hadn’t been attentive enough, lusty enough for

a man of his stature. It was his right to cheat, or so he convinced

her. By the time I was old enough to realize how warped her mind

had become, it was too late for me to intervene. Even as a child, I

could see that my mother had been corralled into cowardice, and

that my father was a lumbering, misogynistic brute. Mine was not a

particularly sunny childhood.

My legs began to pump faster as memories of

my youth flooded my consciousness. I sprinted along the East River,

trying to outrun recollections of my mother’s idiotic, deferential

simpering, and my father’s ruthless, cutting criticism of

everything that I did. Dad was not afraid to raise his hand to my

mother and I. But as many times as he pushed and slapped me around,

no wounds hurt so badly as those he left with his words. I grew up

being told that I’d amount to nothing, that I was a fool to try and

elevate myself above my upbringing.