High Heat (24 page)

Authors: Tim Wendel

Ryan celebrates his fourth no-hitter, which he pitched in 1975 as a member of the California Angels.

National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown, NY

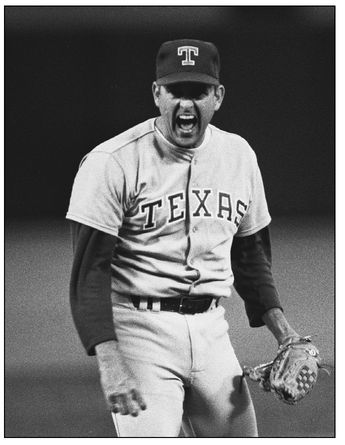

Ryan shows some emotion in the midst of his sixth no-hitter on June 11, 1990, in Oakland. He would record his record seventh no-no the following season against Toronto.

Jose Luis Villegas

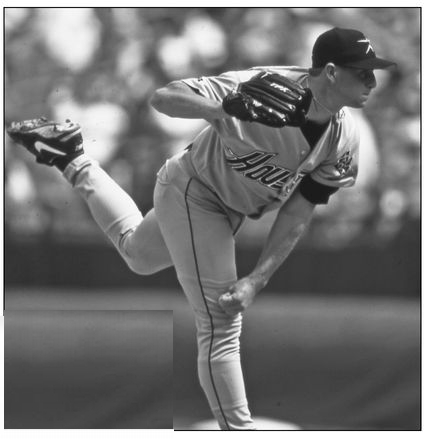

Billy Wagner proves that size doesn't matter when it comes to throwing a quality fastball.

National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown, NY

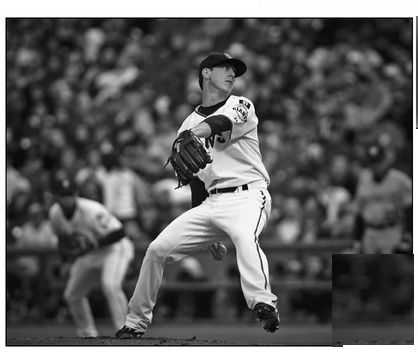

Off the field Tim Lincecum could pass for a skateboarder, but between the lines he's one of the hardest throwers in the game and a Cy Young winner.

Jose Luis Villegas

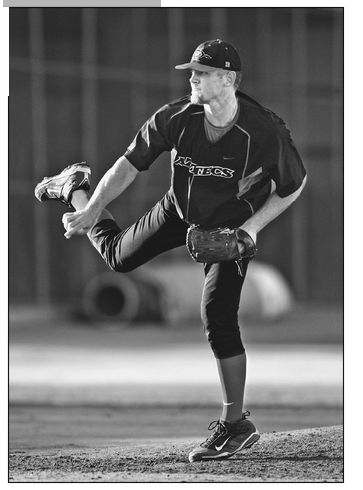

The top pick in the 2009 amateur draft, Stephen Strasburg signed at the 11th hour with the Washington Nationals.

Ernie Anderson

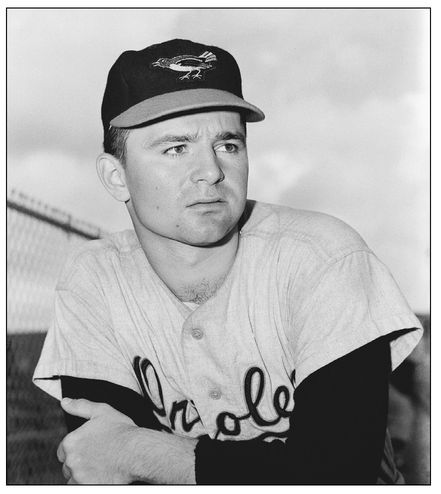

Steve Dalkowski, shown here in 1959, was a legendary fireballer but never reached the major leagues.

Associated Press

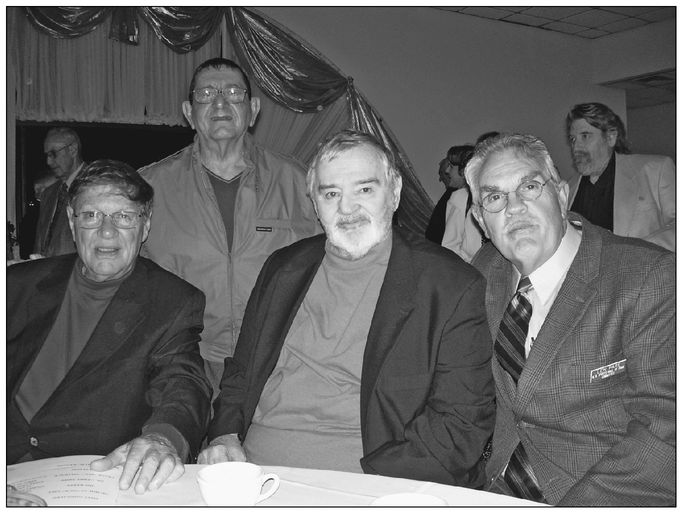

Who says you can't go home again? Steve Dalkowski, center, with several of his boyhood friends at the 2009 spring sports banquet in New Britain, Connecticut.

Tim Wendel

Grove soon gained such a reputation in the Blue Ridge League that Jack Dunn, owner of the Baltimore Orioles, sent his son to Martinsburg for a firsthand look. The younger Dunn was impressed, and one of the most curious deals in baseball was soon completed. One story has it that a recent storm had leveled the outfield fence in Martinsburg. Dunn agreed to pay for a new oneâ$3,000âin exchange for the rights to Grove.

At that time, the Orioles were playing in the International League, and nobody was better. Under Dunn, the ballclub won seven consecutive pennants, and during his four-plus seasons in town Grove went 108â36. Usually winning makes everybody happy. But several of Grove's teammates in Baltimore appeared to resent his success.

“They used to say that I was mean in those days, but I had a reason,” Grove said. “Everybody was mean to me. It was rough on a kid trying to make it in baseball in those days.”

So began the often dysfunctional relationship between Grove and his teammatesâan uneasy truce that would continue throughout his playing days.

In October 1924, the Orioles sold Grove's rights to Connie Mack and the Philadelphia Athletics for a then-record $100,600. By that point, there were three constants when it came to Grove: (1) His stuff was as fast as anything ever seen in baseball; (2) it was just as wild; and (3) his teammates couldn't stand him. “Hitting off him was like asking to be blindfolded and then trying to swing an ax handle to hit a lump of coal in the darkness of midnight,” the

Baltimore Sun

noted.

Baltimore Sun

noted.

Under Mack's tutelage, Grove gained better control of his fastball. In his second spring training with the As he got up early every day and started pitching before his teammates showed up.

“I threw for 20 minutes,” he later recalled. “I put nothing on any pitch. I merely concentrated on hitting different spots of the plate and I finally got so I could throw strikes blindfolded. After that, it was easy sailing.”

So much so that Grove put together one of the most incredible runs in baseball history. From 1929 through 1933, he won 128 games

and lost just 33. Yet it was never easy sailing between Grove and his teammates.

and lost just 33. Yet it was never easy sailing between Grove and his teammates.

“I often was in the need of a helping hand when I came up to the As from Baltimore,” he said of his early years with the As, “but I was never offered one. My victories were greeted by silence. My defeats, all due to wildness, brought no advice as to how I might acquire control.”

In 1931, Grove was on the cusp of breaking the American League's consecutive-wins record. He had tied Walter Johnson and Smoky Joe Wood by winning 16 straight. The record 17th appeared to be a sure thing as he took the mound in St. Louis against the lowly Browns and their journeyman pitcher Dick Coffman. Before the game, Mack had said that Grove was better than his other heralded left-handers, Eddie Plank and Rube Waddell. The stage was set for a coronation. Instead, Grove was greeted with a debacle.

Besides flattering his superstar pitcher, Mack had allowed Al Simmons, the team's All Star left fielder, to take a few days off. Starting in Simmons's place was backup Jimmy Moore. In the third inning, Moore misjudged a fly ball that gave the Browns a 1â0 lead. Remarkably, the tainted run stood up and Grove lost the game, 1â0.

Afterward, he tore apart the visitors' clubhouse at Sportsman's Park. After that he ripped off his uniform, threw it on the floor, and jumped up and down on it.

“If Simmons had been here and in left field,” Grove fumed, “he would have caught that ball in his back pocket.”

Grove didn't speak to Mack or his teammates for several days. He never did forgive Simmons for taking the day off and spoiling his potential record breaker.

To help him concentrate and throw more strikes, Mack urged his fiery left-hander to take more time between pitches, to not rush things. The legendary manager told Grove to count to 10, sometimes 15, between deliveries. Opposing crowds soon caught on and chanted the count along with Grove. Despite being prickly with his teammates, Grove didn't let the distraction bother him. In fact, his walk totals steadily decreased throughout his 17-year career.

Such improvement wasn't enough to keep him in Philadelphia, though. Mack was going broke and began to sell off his stars one by one. Before the 1934 season, after he led the league in victories (24), Grove was sent to the Red Sox. He struggled early on and battled a sore arm, especially during the 1938 season. Yet Grove won 105 games in eight seasons with Boston and finished his major-league career with a 300â141 record. (After he retired, Grove would claim that he could have won 400 if he hadn't spent five seasons in the International League with Baltimore.)

Throughout it all, success went hand in hand with his temper tantrums. After player-manager Joe Cronin's error cost Grove a ballgame late in his career, the left-hander followed Cronin into the Boston clubhouse. Cronin hurried into his office and closed the door behind him. But Grove was never put off so easily. Finding a stool, he climbed atop it, so he could reach the wire screen above Cronin's office. From this vantage point, he sneered down at his manager, shouting obscenities about Cronin's inability to field like a major leaguer.

Then Grove wondered why Cronin and Ted Williams, another teammate he traded insults with, didn't attend a party he threw to celebrate winning his 300th game. Talk about a diva.

“That's the kind of bird Mose is,” former Red Sox general manager Eddie Collins said at the time. “He may never reach the heights of popularity that Babe Ruth has, but it isn't because he isn't a good fellow. He's naturally shy, like most of those fellows from the mountains, and has a natural distrust of strangers.”

Luke Sewell, who batted against Grove for 15 years and later coached in Cleveland, said Grove was faster than the next legend to come down the pike, Bob Feller. “I mean that Grove's fast one actually was past the batter and into the catcher's mitt quicker than Bobby's,” Sewell told the Associated Press. “Feller's fast one, though, had more life to it, and, of course, he had a wonderful curve, whereas Lefty had none until after he began to lose speed.”

“Lefty Grove was the hardest thrower of his era,” Maury Allen wrote in 1981. “[His] fastball would have registered more than

100 miles per hour if the currently used radar gun had been in existence.”

100 miles per hour if the currently used radar gun had been in existence.”

Lefty Gomez was once asked who was faster, Feller or Sandy Koufax. His answer was simply, “Grove.”

“There was probably no better left-hander who ever pitched,” Bill Veeck told the

Washington Star

in 1975. “It's tough to compare different eras and so it is tough to say whether he or Sandy Koufax is better. Certainly no left-hander was better than Grove. His control was his biggest asset. When you throw as hard as he could with his accuracy, you didn't have to do much else.”

Washington Star

in 1975. “It's tough to compare different eras and so it is tough to say whether he or Sandy Koufax is better. Certainly no left-hander was better than Grove. His control was his biggest asset. When you throw as hard as he could with his accuracy, you didn't have to do much else.”

Other books

Iron Hearted Violet by Kelly Barnhill

Letting Go by Jolie, Meg

Only Superhuman by Christopher L. Bennett

The Jade Dragon by Nancy Buckingham

Devil Black by Strickland, Laura

The Case of Naomi Clynes by Basil Thomson

Nero Wolfe 16 - Even in the Best Families by Rex Stout

Couples by John Updike

Begin Again by Evan Grace