High Country : A Novel (30 page)

Read High Country : A Novel Online

Authors: Willard Wyman

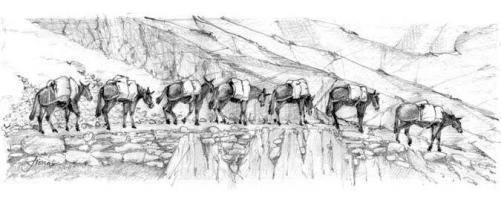

The Sierra Nevada is five hundred miles of rock put right. Granite freed by glaciers and lifted through clouds where water, frozen and free, has scraped and washed it into a high country so brilliant it brings light into night. It lured Indians into its valleys even as it struck terror into the heart of a new world crowding west. It was higher than civilization could go.

Westering men found ways around it, skirted it north and south until they surrounded it. Only then did they creep back to see what had stopped them so completely. Some, probing higher, saw that what healed the glacier-torn range might heal their own wounds as well. A few found ways to be a part of it, to live with it, learn from it.

Ty Hardin became one of those men. Though he went to the Sierra to forget, the Sierra made him remember. It showed him once more that all is in motion, everything is flowing—animals and waters and rocks.That the ground we sleep on and the stars above us all are moving, never ending.

33

33Cold Canyon

It was five years before Ty could tally it up. He was in the Sierra by then, the South Fork and Willie far behind. And it wasn’t until Thomas Haslam’s questions that he could say it aloud.

They were camped in Cold Canyon, a day out of Tuolumne Meadows, the trees edging the high meadow and the late afternoon warm, the wind soft, the Haslam children creeping out to the winding stream, looking for trout, exploring their world—alive with that fragile life that is the High Sierra.

Thomas Haslam had his bourbon out. He and Ty were testing it, Ty thinking back to how seldom Thomas Haslam had thought of a drink when Ty first met him, how comforting he found one now, liking to savor it, watch his children through its richness, think of the times he’d had; the times still ahead—for work, for Alice and their children. Even for the life Ty was leading.

“Do you like this country, Ty?” he asked. “You look as much at home in it as in your own.”

“Higher. Sunnier.” Ty looked at the clouds that had been gathering each morning, the puffs growing day by day, searching one another out until the white would deepen into gray, rain burst from them at last, spilling in sheets to clear again by night, the sky washed, the stars brisk and alive above the moon-splashed granite.

“Don’t have to set up tents every time you turn around.” Ty sipped his bourbon. “It’s a predictable country. At least this time of year.”

“And you don’t have to worry about grizzlies,” Haslam added.

“I never worried about them.” Ty looked at him. “I believe it’s their worryin’ about us that made everyone so nervous.”

But the death of the red bear should have warned him, a happening so sudden and violent he was numbed. The loss of Willie and the child was less numbing than final, bringing a heaviness that settled in like silt.

Thomas and Alice had read about it. It was in the papers all over the country. Two experienced hunters, exploring the little-known canyon. The huge red bear rising from the aspen grove, rising unbelievably high, watching them, scenting them until they fired on him together, firing again and then again until he was upon them, his charge breaking the arm of the one who lived—the one he flung away as he mauled and shook the other like some toy whose parts must never work again.

They’d read about the man with the dangling arm, blood dripping from his wounds, running and running until he’d come to the one packer who used the canyon, who on a whim had decided to take the season’s last party through the wild canyon he knew as no one else did. The wounded man collapsing there, unable to go back with the packer—unable and afraid beyond reason. The packer had left him to be nursed by an ancient cook and two bankers and their wives, couples on their first trip into a country they would never want to see again.

They’d read about the packer finding the broken man still alive but knowing he shouldn’t be, couldn’t be for long. The packer watching the bear circle before charging back, the packer shooting and shooting and shooting until the huge beast dropped, almost upon them—the life gone from him at last.

And later Ty told them himself, told them what he’d told the Forest Service and the reporters and biologists and naturalists who had called and written and come to him, come to hear him and to examine the vast tawny pelt. The pelt that would soon hang behind the desk of the Forest Service supervisor so the young men of the Forest Service could see it, know what they were protecting. Know what they had to fear.

But telling it as he had had never meant thinking about it the way he did that afternoon in Cold Canyon. He told Thomas Haslam about hesitating over the hunter’s torn body, watching as the wounded bear circled, wanting him to leave, nurse his great hulk deep in some hidden glade—live to reclaim his canyon, his solitude. About the bear’s finally charging after all, as though to go out with these men who had betrayed him, injured him so deeply, go out with them or fix them so they could never injure anything again.

And so Ty had had to shoot, his bullet going to its mark but the bear withstanding even that, and another shot still. Only the final one, fired into the huge bear’s anguished mouth, had finally put it all to rest.

And he told him about turning to the dying hunter, the blood bubbling from the torn face, an ear and the scalp gone, an arm all but ripped away, a leg broken and akimbo, the man speaking through the orangy froth of his battered lungs, Ty bending to hear him say, “Kill me.” The voice pushing blood from the torn mouth. “Kill me.”

But Ty not able to do it. Knowing he should but turning away, stumbling back—leaving some part of him behind with the huge bear and the dying man and the torn earth. He returned with the others to find the broken life still there. No talk from the ravaged body now, just the bubbling flecks of blood telling them how stubborn, against reason, life can be.

They stopped in Fenton’s old camp, brought in what was left of the man on a crude litter, made a place for him to die as Ty dressed the wounds of the other, fashioned a splint for the arm just as Fenton had fashioned one for Bob Ring’s leg in what seemed to Ty another life, another place.

The hunter died in the deep darkness of the overcast night. Ty mantied him up in the morning and packed the broken body out on Cottontail, as steady a mule as he had for a task more somber than any he’d ever known.

Word came out ahead of them. The Forest Service was there, waiting. Two of Spec’s cousins, skinners, were already going back in to weigh and measure and dress out the great bear. The officers did their duty: sent the broken hunter on to the hospital, took the mantie from the torn body of the other, examined it, sat down with Ty to write their reports, to answer the hard questions reporters were asking. The reporters astonished as they looked from the body to the mountains and back to the haggard packer, wanting more but making do with the spare facts he offered.

“Hard to know what ate at me so,” Ty told Thomas Haslam. “Must have been that the bear could live with us so long—with Fenton and Spec and the rest. Like we lied to him. To ourselves.”

“About what?” Haslam asked. He was moved hearing Ty speak this way. “You had to pull that trigger.”

“Not about that. By then one of us had to go.” Ty looked out across the meadow, watched his horses moving higher, seeking the sun. “I mean about thinking we could have it forever.”

Thomas Haslam thought of all those deaths pouring in on Ty at once, everything he’d counted on gone.

“I’m sorry about Willie,” he said simply, looking at Ty. “The child.”

“Maybe it was in the cards,” Ty said. “Maybe she saw something coming.”

If Willie did see anything coming, Ty never knew it. She was Willie until the moment they wheeled her into the delivery room. But she’d known shooting the bear had changed him, seen that look on his face when he came down from the mountains. It was the same he’d had after Fenton died. After Cody Jo left. The same look he’d had after Bernard.

Ty hadn’t wanted to seem gloomy. He’d taken Willie dancing, big as she was. But she’d known something was missing. Something about the promise, always there in the way he danced, was gone. He couldn’t lose himself in the music, surrender to its rhythms.

When the Sister of Providence came to him, the same who’d counseled Willie in school, saying her prayer in that clear, beautiful voice, Ty knew. He hardly heard the doctor’s explanation. “Tried to hold the blood, save the child, the rupture unexpected.” He’d turned away as though there was no need to hear at all, walked the night away through a town suddenly strange to him, across a campus finished for him, past houses closed to him.

And so they talked, Thomas Haslam and Ty, the doctor knowing most of it but not how it had come to Ty, not until that afternoon in Cold Canyon when Haslam found he had to swallow his own feelings away. Glad as he was that Ty could finally talk it out, he found it hard to hear it out, to watch Ty’s face—the acceptance in it, the finality.

The Haslams had been in the South Fork with Ty earlier that very season, bringing with them Opie Kittle, a packer whose sons wanted nothing to do with the Sierra pack station the Kittle family had run for almost a century. They’d told Kittle about Ty, and it hadn’t taken the old packer a day of watching Ty work before he offered him a job. By the end of the trip he’d offered him half-interest in his whole operation, which had only made Ty smile. Opie Kittle saw why when they came out of the woods and Willie was there, her belly a watermelon and her voice clear as mountain water.

“She’d make any man stay to home,” he said to Ty. “But things change. Write when you’re ready. Ain’t seen a packer like you in a lifetime.” He squinted up at Ty, liking everything about him. “High country’s just right for you. And where I pack is the highest we got.” He watched Ty settle Cottontail’s breeching between the sawbucks, swing the breast collar onto that, the cinches up across all of it, lifting the saddle and pads together, switching them so the pads would dry where he stacked them. “It’s where you ought to be.”

Thomas Haslam reminded Ty of that when he came from San Francisco for Willie’s funeral. All of them were there, Cody Jo and Bliss Holliwell too, even Beth and Loretta, trying not to be noticed but tearing up when they saw Ty.

He was with Bob Ring, looking at them all, speaking to them all. But it was as if he didn’t see them at all, as if he were a wooden man being told where to turn and what to say.

They buried Willie and the child in the Catholic cemetery next to Willie’s mother. Bob Ring limped along behind the coffin with Ty, his face creased—everything about him looking older with each crooked step he took. Ty seemed to be looking beyond the coffin, beyond everyone, looking at something else, someplace else.

Cody Jo began crying, holding Buck’s arm as though it might save her from something, burying her face in his shoulder.

“Oh, Buck. He’ll never have it now. I thought someone like Willie . . .” Buck held her, his eyes wet as he looked across her buried head at Bliss Holliwell, whose face was just as anguished as Buck’s.

“I was so wrong.” She looked from one to the other through her tears. “How could I have been so wrong?”

Ty didn’t seem to hear it when Thomas Haslam reminded him of Opie Kittle. He didn’t seem to hear it when the banker called him in and told him they would continue with the mortgage on the house but couldn’t be responsible for the back-country, wanted him to convert the packing business into day rides, start a guest ranch, do what was safe.

But he heard something when Opie Kittle called and told him he still wanted Ty to come and run things, that the half-interest offer held. He didn’t even seem to consider it, just said he would come.

Two weeks later Cody Jo heard about it. She wrote telling the banker to sell, to settle the cash on Ty, that she’d take care of the details.

When it was done, there was enough for Ty to buy a decent truck and a four-horse trailer and have some left over.

When spring came, he loaded Smoky and Cottontail and Loco, deciding to take little Apple too. She wasn’t young anymore, but she was Willie’s.

“They won’t miss her,” he told Buck, who helped him load. “Won’t be much use to them anyhow.”

But Buck knew better. Buck knew Ty wanted to take some of Willie with him when he left.