Hieroglyphs (3 page)

Authors: Penelope Wilson

Tags: #History, #Africa, #General, #Ancient, #Social Science, #Archaeology, #Art, #Ancient & Classical

the real stores could be accounted for. The royal stores no doubt

ogly

comprised goods from all the king’s domains and trading contacts

Hier

and each of those places must have had its own accounts recording the taxes and tributes due to the king, what was actually paid and when it was sent to the residence. The tomb is the tip of the iceberg of a huge state organization and the use of writing in it hints at the huge accounting machinery at work in the background. It may seem less than glamorous to suggest that the invention of writing happened for taxation purposes, but whether material is recorded for the warehouse or for the afterlife, it is part of the same process.

The tomb too was a focus for the display of the cult practices surrounding the dead king and was not only the means for transferring him to another sphere of existence with the ancestor gods, but provided a restricted arena for the display of his power and status. In this sphere, the tomb architecture funnels life-restoring power to the king’s spirit, whose existence is assured by the presence of hieroglyphs naming him.

8

Den (or Dewen) was one of the first great kings of Egypt, around 2800 bc. He ruled a united kingdom centred on the capital city at Ineb-Hedj, ‘White Walls’ (Memphis), and his tomb at Abydos is a good guide to how much written material might have been produced at that time.

At the entrance of the tomb were two monolithic stelae – inscribed stone slabs bearing only the name of the king. It was written inside the

serekh

-rectangle, with a falcon representing the god Horus standing upon it. Inside are the two hieroglyphs spelling the king’s name: a human hand and a zig-zag water sign, Den. Inside the tomb many inscribed labels and jar sealings were found and they also record a second name of the king which is read either as Khasety or Semty. Some of the labels record ‘events’ or ‘festivals’ in

Th

the reign of the king and served as a yearly account (annal) of his

e origins of writin

rule. They record the kind of living myth that is the life of a successful king.

A close examination of one of Den’s labels from Abydos shows how

g in E

far the use of hieroglyphs and pictures had come up to this point.

gypt

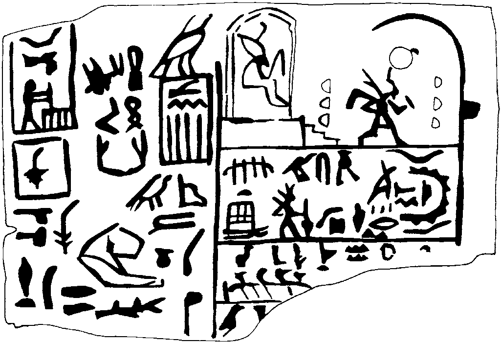

2. Label of Den from Abydos.

9

The wooden label (British Museum 32.650) measures 8 cm by 5.4 cm and the text on it reads from right to left. At the top right of the label is the attaching hole and the tall vertical sign at the very right is a notched palm rib meaning ‘year’, so this reads, ‘The Year of . . .’. The scene at the top right shows a figure seated on a stepped platform inside a booth. He wears a White Crown and holds a flail of office. In front of him a figure wearing the Double Crown of Upper and Lower Egypt and holding a flail and rod is running around two sets of hemispherical markers. The event is the Sed-festival, when the king proved his fitness and strength after a period of time in office by running around a marked course.

The scene below is less clear but seems to show a walled enclosure containing several hieroglyphs, perhaps the name of a town. To the left is what was originally interpreted as a small squatting figure of a woman with several hieroglyphs in front of her which may be her name. Behind her is a man wearing a head-dress and carrying an

phs

oar and a staff. Three hieroglyphs above him show a vessel with

ogly

human legs, a bolt of cloth, and possibly a vulture sign. Behind him

Hier

the two top signs spell the second name of Den and the lower sign is some sort of portable shrine. The damaged scene below contains bird, land, and plant hieroglyphs. The large area to the left contains the

serekh

bearing Den’s name and to its left is a title, ‘Seal bearer of the king of Lower Egypt’, and the name ‘Hemaka’ (written with a twisted rope, a sickle, and a pair of arms). Hemaka was an important and powerful official of Den. To the left is another rectangle containing signs, of which the last one is a word meaning

‘to build’. Beneath is a word meaning ‘House of the King’. The hieroglyphs in the lower left part of the tablet can be recognized and mention the ‘Horus Throne’ and a dais. They seem to record further that the label was used on a jar of oil, perhaps recording its date of production or precise provenance. Alternatively, the oil may have been symbolically connected with the events depicted, either as anointing oil or offering oil. The tablet records ‘The year of a Sed-festival, Opening the festival of the Beautiful Doorway’, and perhaps something connected with the building of the king’s palace.

10

As is clear from this part-interpretation, the signs have much information to give and act as a fully fledged writing system.

Altogether fragments of thirty-one such ‘annal’ labels are known from Den’s tomb and they mention events such as the ‘Journey of the

Reput

on the Lake’ or ‘Capture of the wild bull near Buto’. There is a clear tradition of recording events both with cultic and economic benefits. Other inscribed objects were found in Den’s tomb including stelae with the names of people buried with the king, inscribed game pieces, and jar sealings. Some of them repeat

‘cultic events’ from the labels such as the Lower Egyptian king spearing a hippopotamus and, of course, record the name of the king. The most interesting personal object from Den’s tomb was the lid of an ivory box inscribed to show that it had contained his own

Th

seal of of

fice.6

e origins of writin

There is also a hint that in cult temples the display of royal power was dependent on the integration of hieroglyphic writing and organized depictions of rituals or commemoration of events. The

g in E

most famous example from this time is the Narmer Palette, apparently of Dynasty 0–1 (

c

.3100

gypt

bc) made of slate and decorated

in raised relief. Found at Nekhen, it shows King Narmer, his name written with catfish and chisel hieroglyphs, as king of northern and southern Egyptian kingdoms. As the king of the southern Egyptian kingdom, probably centred on Nekhen, Narmer is about to brain his enemy, who is shown as culturally different. His death is not shown because the moment depicted is the precise second before the king acts – he can take life or give life. As the king of the northern Egyptian kingdom, perhaps centred on Nubt (Ombos), the king takes part in a victory parade surveying the decapitated bodies of his enemies and accompanied by a boy or man carrying his sandals and by a person wearing a heavy wig and leopard-skin garment. The figure is either his chief minister or a high-ranking priest. Though palettes were used to grind down pigments for use as bodily adornment, the size of this palette, its decoration, and the hieroglyphs on it suggest it was meant for display in processions or 11

in the sanctuary of the temple to Horus at Nekhen. It commemorated the acts of Narmer and his devotion to the god Horus.

Materials

By the time of the Early Dynastic Period the principles of writing must have been firmly embedded in the system of kingship in Egypt for such a complex society to be able to run a cohesive administration. In this case, clearly, the writing and the ideas behind it came much earlier, but it is difficult for us to trace all the stages of its development. The painted Naqada pottery is hardly a full written document, but if such early documents were woven mats, papyrus, wooden boards, clay, or mud, they have not survived because they were not buried in the cemeteries whence much of the material has come.

phs

The development of papyrus was also a crucial factor in the

ogly

growth of writing as a means of communication. It is made from

Hier

the reedy and abundant pith of the papyrus plant, which, when hammered together in thin strips and dried, forms a good, smooth writing surface which is easy to carry and could be rolled up and used several times. We know that the Egyptians were expert mat and basket weavers and so were used to working with all kinds of reeds and grasses from Neolithic times onwards. It is likely that they had experimented with making papyrus in the Predynastic period and with using it as a writing or painting surface for ‘portable’ messages. As can be seen from the early royal tombs, a vast range of writing surfaces were used: labels of bone, ivory, and wood on jars for incised inscriptions; jars for ink inscriptions; stone stelae inscribed with the king’s name; flakes of stone painted with images (ostrakon). There are also mud seal impressions, again showing the ownership of various jars and their contents by the king. A roll of papyrus was found at Saqqara in the tomb of Hemaka, an official of Dynasty 1, but it was blank and unused.

12

Seal impressions are in themselves important as a means of easy replication of written signs, for one seal would be used to create a large number of impressions. Some of these early seals have survived in the form of a cylinder made of stone or wood. The

‘cylinder seal’ had a hole through the centre and the outside of the cylinder was incised in sunk relief with the writing, usually of the king’s name or other words or a scene. When a string or stick was put through the hole it could be rolled over wet clay or mud and the impression of the seal would be left standing proud on the surface of the mud. Though this is a typical method of sealing jars in early Egypt, the cylinder seal was probably a Mesopotamian invention.

The fact that the Egyptians adopted the cylinder seal has led to the suggestion that the idea of writing, and of writing in pictures (hieroglyphs) in particular, originated in Mesopotamia.

Th

e origins of writin

Mesopotamian influence?

Mesopotamia was the land between the two rivers of the Tigris and Euphrates, an area in modern Iraq. Around 3500 bc the

g in E

Mesopotamian civilization based on the land of Sumer, with its capital Ur, was a powerful complex society with cities, a system of

gypt

writing, and a fully developed administrative system to supervise tax collection and to manage surplus agricultural resources. It is likely that there was some kind of communication with the Nile Valley, perhaps by means of sea routes or by land routes giving access both to northern Egypt and through the wadi channels to Upper Egypt and the first main centres at Naqada, Nekhen, and possibly This. Mesopotamia may have needed raw materials such as gold, grain, or stone from Egypt, and Egypt may have wanted commodities such as tin and timber from Mesopotamia. There also seems to have been an exchange of invisible exports/imports such as technological ideas, cultural developments, and people. In Egypt it is possible to see some Mesopotamian technological and cultural traits during the Predynastic period and the beginning of the Early Dynastic Period: mud brick, niched facade architecture, subterranean houses (both at Maadi), and the ‘man taming the 13

beasts’ artistic motif (Tomb 100). Among the ideas which came to Egypt could have been the idea of picture writing. In Mesopotamia, the Sumerian language was written in a pictorial script on clay tablets and carved on seals. Writing was used from around 3500 bc, particularly for documenting transactions and keeping accounts by the state administration. It may never be possible to tell from the archaeological evidence exactly how far Egypt was influenced by external factors, but if there had been contact, the Egyptians went on and developed their own writing system and its uses in their own way without drawing anything further from outside.

As more archaeological work is done in Egypt the evidence for the use of writing at earlier periods than is currently known may come to light. It also seems likely that any early contacts between Egypt and Mesopotamia will have left no real trace and that ultimately both civilizations developed their writing systems independently.

Contacts between contenders are difficult if not impossible to

phs

determine but as both have similar geography and agricultural

ogly

practices, it is no surprise that both would have the same

Hier

requirements for the control of the state and its resources. It is interesting that in Mesopotamia the pictorial form of the script was dropped very early in favour of a much more efficient writing system using small wedge shapes called cuneiform. The Egyptians, meanwhile, developed a dual form of writing and kept the pictorial script for special purposes.

Stimulus and rule

In the case of Den’s tomb, writing was used to name and identify, to keep accounts and to record specific cultic events pertaining to the king. The commemoration of these basic records achieved a cultic status of which the Early Dynastic tombs and Early Dynastic temple deposits are our only archaeological evidence. It is likely that they only refer to the rather rarefied élite sphere and record their concerns. The impression given is that in the valley and delta settlements writing was used more rarely for royal commemoration.

14

This cannot possibly be the case for every place, however, and the main administrative centres of Egypt will have had written documents of many types which have not survived. Indeed the success of the Egyptian state was based on the mass organization of agricultural surplus, so that it could be used to feed those who worked on non-agricultural projects for the king such as craftsmen, bureaucrats, the army, and members of quarry expeditions and the royal court.