Hidden History: Lost Civilizations, Secret Knowledge, and Ancient Mysteries (46 page)

Read Hidden History: Lost Civilizations, Secret Knowledge, and Ancient Mysteries Online

Authors: Brian Haughton

Tags: #Fringe Science, #Gnostic Dementia, #U.S.A., #Alternative History, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #Archaeology, #History

Researchers insist that the possibility of finding a living example of

Homo floresiensis or Ebu Gogo should

not be dismissed out of hand, particularly as Southeast Asia is a relatively

rich area for finds of mammals unknown to science. Examples include an

antelope, Pseudoryx nghetinhensis (described from the Lao-Vietnamese border as recently as 1993) and the

kouprey, an ox-like creature (known

to Western science only since 1937).

Bert Roberts and Michael Morwood

are convinced that exploration of the

remaining rainforest on Flores and

caves associated with the Ebu Gogo

stories could provide them with vital

samples of hair or other material, perhaps even living specimens. They also

think it probable that the skeletal remains of other, equally divergent Homo

species, await discovery in other isolated corners of Southeast Asia. Indeed, the fact that a lost Homo species

such as floresiensis, which had lived

so recently, yet remained unknown

until 2003, strongly suggests there are

more significant gaps in our understanding of the history of humanity

than we could ever have imagined.

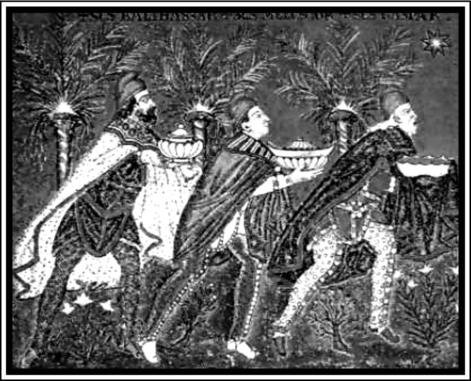

The Three Wise Men, named Balthasar, Melchior, and Gaspar, from a late 6th century

mosaic at the Basilica of San Apollinare Nuovo, Ravenna, Italy.

The Magi are familiar to most

people as the Wise Men from the East

in the Bible. The Gospel of Matthew

describes them following the Star of

Bethlehem to find the savior and offering him their gifts of gold, frankincense, and myrrh. But did these

mysterious wise men bearing exotic

gifts really exist outside of this biblical story? And if so, what was the Star

of Bethlehem?

The word Magi (the plural of the

term Magus), comes from Latin via the

Greek word Magoi, itself borrowed

from Old Persian Magus. The Old English word is Mage, and it is from this

that we get our word magic. One of the

earliest mentions of the Magi is by the

Greek historian Herodotus (c. 484 B.C.-

c. 425 B.C.) who states that they were a

sacred class of priests living in Media

(roughly the northwestern part of Iran

and the area of Kurdistan), and one of

the six tribes that composed the original Medes. However, as the Persian

Empire expanded into their area in the

sixth century B.C., the priests of the old

Median religion, which was possibly

of Mesopotamian origin, found it necessary to adapt their practices to the

monotheistic Zoroastrian faith, though

this was a slow and painful process. It is recorded that when Darius the

Great, Persian Emperor from 521 B.C.

to 486 B.C., and one of the early kings

of the Achaemenid Dynasty (c. 560 B.C.-

330 B.C.), discovered that the Magi at

the Median court were skilled interpreters of dreams, he established them

in preference to the state religion of

Persia. Whatever the truth of this, by

the time Herodotus was writing, the

Magi had become priests in the Persian Zoroastrian religion, with a role

comparable to Shamans or medicine

men. Part of their duties was to serve

as astrological consultants to the Persian emperors, and they soon attained

a powerful religious influence and

earned respect as wise men throughout the Empire.

An important source for the

Magians under Darius are the

Persepolis Fortification Tablets, a substantial collection of ancient Persian

cuneiform administrative texts, dating

from between 506 and 497 B.C. It is in

these texts that the Magi are described

as operating in a dual capacity, wielding both religious and political influence. This combined function of

administrator and priest was a common practice in Near Eastern societies at the time. The Magi were given

important religious responsibilities,

as is illustrated in the description of

the tan-sacrifice at the Persian capital city of Persepolis. As the tablets

describe the Magi as fire kindlers, this

ritual seems to have been a type of fire

sacrifice to Ahuramazda (the wise

lord), the supreme god of the ancient

Persians. Together with the testimonies of ancient Greek authors, the Fortification Tablets indicate that the

Magi were present at the royal court

of the Persian emperors, and involved

at the very highest level in Persian

religious practice and administration.

With the invasion of Persia by

Alexander the Great in the winter of

331 B.C. the Achaemenid Dynasty came

to an abrupt end. Although ancient

sources mention Magi at Alexander's

court being involved in rituals of some

sort, it is also clear that Alexander

destroyed many Zoroastrian sanctuaries, probably because he saw their religion as a threat to his authority.

The Greek writer and geographer

Strabo (c. 63 B.c.-c. A.D. 21) describes a

sect of Magians in Cappadocia (central

Turkey). He called them fire kindlers,

who possessed fire temples containing

an altar on which a fire was kept continuously burning. The Magians visited the temple daily for around an

hour, where they would make incantations holding bundles of tamarisk or

other branches in front of the fire and

"wearing round their heads high turbans of felt, which reach down their

cheeks far enough to cover their lips."

It seems that some Magi also traveled

west, arriving and settling in Greece

and Italy. Traces of their beliefs and

practices can be found in Mithraism,

an ancient mystery religion based on

worship of the god Mithras, which became popular among the Roman Legions around the third to fourth

centuries A.D. At the time of the Roman Empire, the word Magi began to

be used as a more general term to describe any representatives of an eastern cult, and by the time of the birth

of Jesus, it had come to mean anyone

involved in magic, astrology, or dream

interpretation. The Magi seemed to

have been accepted as part of the courts of the Roman Empire, as a number of them are mentioned as accompanying high ranking officials and

governors.

The description of the Magi in the

Gospel of Matthew (written between

A.D. 60 and 80) visiting Jesus in

Bethlehem is the only source we have

for the event. The text says "there came

wise men from the east to Jerusalem"

and subsequently refers to the Magi's

interest in stars, so it is probable the

wise men he is speaking of were astrologers. This concern with the stars

has suggested to some that the wise

men came from Babylon, a well-known

center of astrology at the time. However, to judge purely by the nature of

the gifts they brought-gold, frankincense, and myrrh-Arabia would seem

more appropriate, though it did not

possess a Magian priesthood. Matthew

never mentions how many Magi there

were, but the number of gifts would

indicate three. The nature of these

gifts has potent symbolic power for

Christians: frankincense signifying

Christ's divinity; gold representing his

royalty; and myrrh, which was used in

anointing corpses, a symbol of the

forthcoming Passion and death.

According to the Gospel of Matthew, before arriving in Bethlehem,

the Magi first visited Herod, the Roman puppet king of Judea. After sighting the star in the east, they made

inquiries with Herod regarding the

new king. Herod, with his knowledge

of Old Testament prophecy, was able

to direct them to Bethlehem. He requested that the Magi return to see

him when they found any news, so that

he too could pay homage to the newborn savior. As they approached

Bethlehem, the star again appeared in

the sky so the Magi followed it until

they found the King of the Jews and

presented him with their gifts. The

astrologers were subsequently warned

in a dream to avoid going back to Herod

and traveled back to Persia by an alternative route. As a result of this

trick, Herod was furious and ordered

the massacre of the Holy Innocents, all

the children under two years old in

Bethlehem and the surrounding area.

But by then Joseph had taken Mary

and Jesus to safety in Egypt.

There has been a huge amount of

discussion about what kind of star it

could have been that brought the Magi

out of the east on their long trek to

Judaea. Explanations put forward for

this astronomical wonder include meteors, the planet Venus, planetary conjunctions, stella novae, comets, and

even UFOs. Nowadays, the two most

widely accepted suggestions are that

the star in the east was either the

planet Jupiter, or Halley's Comet.

The Greek word aster, used by

Matthew in his gospel to describe the

Star of Bethlehem, can be interpreted

to mean a comet. But is there any

record of a comet at this time? In the

Roman world there was a belief that

the appearance of a comet often heralded catastrophic political events,

even the death of an emperor, which

would suggest that it could not be associated with the birth of a new messiah. But among the Magi of the Black

Sea coast of Turkey, comets appear to

have been good omens. The successful

rule of one particular king in the area,

Mithridates VI, was so much associated with comets as positive celestial

portents that he even had coins minted depicting them. The appearance of

Halley's Comet in 12 B.C. caused consternation throughout the Mediterranean world, especially in the skies

above Rome. Because Herod is now

believed to have died in 4 B.C. most

scholars now place the birth of Jesus

somewhere between 12 and 4 B.C.,

which would make Halley's Comet a

possibility for the Star of Bethlehem.

A problem with the comet theory however, is that Matthew mentions that

Herod and the people of Jerusalem did

not notice the star of Bethlehem in the

night sky, which they surely would

have done if it was something as obvious as Halley's Comet.

Jupiter, known as the star of Zeus,

was traditionally the planet associated

with kings, and astronomer Michael R.

Molnar of Rutgers University in New

Jersey has interpreted statements in

Matthew's Gospel that the star "went

before" and "stood over" as referring

to to the reversal of motion and stationing of the planet Jupiter. Molnar

has discovered a Roman coin issued in

Antioch, the capital of Roman Syria,

which dates to the time of Jesus' birth

and which depicts the astrological sign

of Aries the Ram turning its head to

look back at a star. Molnar believes

that this coin was issued to commemorate the takeover of Judaea by Roman

Antioch in A.D. 6. Subsequent research

revealed that in an important astrological work by Claudius Ptolemy, the

Tetrabiblos, Aries the Ram is explained

as controlling the people of "Judea,

Idumea, Samaria, Palestine, and Coele

Syria"-all territories ruled by King

Herod. So it is possible that the star

on the coin represents Judaea's destiny in the hands of Roman Antioch.

This may indicate that astrologers

were waiting for the birth of a great

king of the Jews portended by the appearance of the Star of Bethlehem in

the constellation of Aries the Ram.

Molnar's research shows that the celestial events on April 17, 6 B.C., when

Jupiter was in Aries and there was

also a lunar eclipse of the planet, were

exactly those which would indicate the

birth of a divine person. Though a lot

more research needs to be done on this

theory, it provides the best evidence

yet that the Magi from Persia were

actually following a real star, in this

case Jupiter, which would ultimately

lead them to Bethlehem and the future

King of the Jews.