Here Comes the Night (6 page)

Wexler had grown up insolent and conniving in the streets of Washington Heights. A street-smart wiseacre who spent more time in Artie’s Poolroom than any classroom, Wexler had read just enough books to be dangerous. His father was a Polish immigrant who worked his entire life as a window washer. His mother was a real character, a card-carrying Communist and modern woman with grand designs for her reprobate son. When he flunked out of college in New York, she sent him packing to Kansas State University, thinking he couldn’t get into trouble in the middle of all those cornfields, only to have her derelict, jazz-mad boy spend his time in gin mills in Kansas City, where he saw Big Joe Turner working as a singing bartender. He didn’t last the second year. He came home to a dismal life, ennobled solely by the grace of jazz. By day, he washed windows alongside his father. By night, he haunted the music emporiums of Fifty-Second Street and Harlem, far removed from the daylight drudgery as he shared a joint with his hipster friends in the basement of Jimmy Ryan’s.

He was drafted during the war but served only in Florida and Texas. He completed his journalism degree at Kansas State after his discharge and moved back home to Washington Heights. He was thirty

years old, married, living with his in-laws, yet to find his first real job. When he finally found work at the weekly music industry trade magazine

Billboard

, Wexler felt perfectly at home among the pluggers and cleffers on Broadway, the rack jobbers on Eleventh Avenue, hanging out at the bar at Birdland. He tipped Patti Page’s manager to a country song, “Tennessee Waltz,” that would make the girl thrush a major star. After he left

Billboard

for old-line publishers Robbins, Feist, Miller, Wexler introduced Columbia Records a&r director Mitch Miller to a couple of big numbers in 1951—“Cry” by Johnny Ray and “Cold, Cold Heart” by Tony Bennett, which took country songwriter Hank Williams into the pop charts for the first time. But Wexler hated his job, playing stooge to some old-time Alley sleazebag. He thought the Atlantic guys were the cognoscenti of the cognoscenti and he aspired to their level of cool.

Wexler came to work in 1953 at the Atlantic offices at 234 Fifty-Sixth Street, above Patsy’s restaurant. It had been a speakeasy during Prohibition called the 23456 Club, and the creaky, excruciatingly slow elevator belonged to that bygone era. Most visitors preferred the rickety wooden staircase. Atlantic occupied the top floor. A stockroom took up the back. In front was one big room with several desks and a grand piano. Wexler and Ahmet sat side by side, although Wexler arrived early in the morning and Ertegun never showed up before noon, sometimes not until hours after that.

When they held recording sessions, they stacked one desk on top of the other and pushed them to the side of the room and rolled the chairs into the stairwell. Tom Dowd, whom the company hired exclusively to make their recordings, made some modest improvements on the recording equipment. The floor sagged and creaked. There was a skylight in the middle of the sloped ceiling. The company sometimes still rented time at outside recording studios, but mainly this was where Atlantic operated at the time Big Joe Turner came into the makeshift studio for a historic February 1953 session to record “Shake, Rattle, and Roll.”

Atlantic had made a record the previous year with Turner in New Orleans, but the principals weren’t even on the scene—they just sent Turner into the studio with a bunch of local New Orleans players (who included pianist Fats Domino) and he came back with “Crawdad Hole” and “Honey Hush.” Ertegun and Wexler did meet up with him in Chicago in October 1952 and recorded “TV Mama” with Chicago guitarist Elmore James, and they cut “Midnight Cannonball” with him in December in New York.

Jesse Stone wrote “Shake, Rattle, and Roll” under his pen name Charles Calhoun. They pushed the desks to the walls and brought the camp chairs out. Ahmet, Wexler, and Stone barked the background vocals. Pianist Harry Van Walls rippled little boogie-woogie triplets under the song’s rhythm and Turner croaked Jesse Stone’s vivid eroticism: “You wear those dresses the sun comes shinin’ through / I can’t believe my eyes all that mess belongs to you.”

“Shake, Rattle, and Roll” was one of those mythical convergences of personalities, history, and music, frozen in time through the majesty and mystery of magnetic tape recording. It is an entirely unself-conscious record that does not recognize or acknowledge the rapidly changing audience for the music; it is the epitome of the classic unfettered rhythm and blues record, a great, roaring blast of lust and boogie-woogie that echoes through the years. When Bill Haley and His Comets recorded “Shake, Rattle, and Roll” the following year, the lyrics were cleaned up, the arrangements pepped up, and the foreboding, ominous mood of the original dissipated, but the song’s irresistible beat remained. The Haley record cracked the pop Top Ten, sold more than a million copies, and was one of the key records in the emergence of rock and roll.

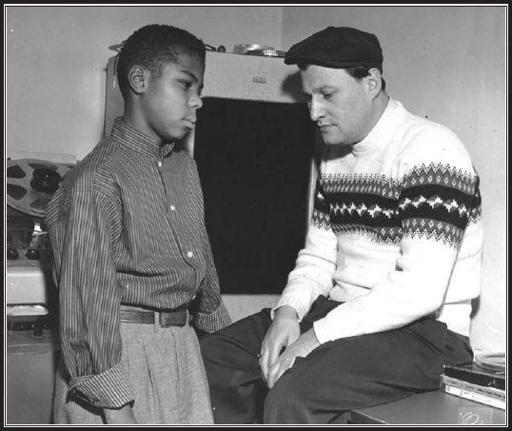

At some point, Herb and Miriam Abramson had given Ahmet a copy of the 1951 record “Baby Let Me Hold Your Hand,” on a small West Coast label called Swing Time by an artist named Ray Charles. Ahmet couldn’t stop playing it. Sixteen-year-old Ray Charles

Robinson, who went blind as a child shortly after watching his brother drown, left blind school in 1946 in Florida an orphan and took a bus to Seattle because that was as far away as he could get from Florida. He gigged around the Seattle area, polishing his Charles Brown imitation, and was working as piano player and musical director for bluesman Lowell Fulson when Atlantic bought his Swing Time contract for $2,500 in 1952.

At the first Atlantic session with Ray Charles in New York, the strong-willed pianist tangled with arranger Jesse Stone over musical ideas, but when he returned for a second date in May 1953, Stone stayed out of Charles’s way, sensing someone who needed to express himself. Ahmet warmed up Charles at rehearsal the night before, enthusiastically singing with Charles, accompanying him on a song Ertegun had written called “Mess Around.”

“Hold your baby tight as you can,” Ertegun half sang, half shouted, “spread yourself like a fan and do the mess around.”

While his new partner Jerry Wexler watched goggle-eyed from the other side of the glass, Ahmet leaned over the piano and walked Charles through the wiseacre blues, “It Should Have Been Me.” Charles sprayed little bursts of Bud Powell bop and Jimmy Yancey boogie-woogie between takes. On the tape of the evening, he sounds like nothing so much as someone searching for his voice. The next day’s session yielded his first chart hit for Atlantic, “It Should Have Been Me,” the talking blues Ahmet had deftly demonstrated.

A month after the Ray Charles session, Ahmet was in the studio with a new group called Clyde McPhatter and the Drifters. He went to Birdland to see Billy Ward and the Dominoes, an oddball booking. Ahmet thought the world of Clyde McPhatter, the lead tenor of the Dominoes, best known for the raunchy 1951 hit “Sixty Minute Man,” although McPhatter sang lead on the group’s 1951 debut, “Do Something for Me.” Ahmet felt McPhatter’s voice had a magical, almost angelic quality. Ward was a tough cookie who ran a tight ship

and levied harsh fines for perceived infractions. Ahmet immediately noticed that McPhatter was missing from the lineup at Birdland, went backstage at intermission, and learned that Ward fired McPhatter five days before. He rushed to a phone booth, looked in the book, and found several McPhatters listed. On his first call, he reached Clyde’s father, who handed the phone to his son. McPhatter came to the Atlantic offices the next day and they cut a deal.

After the June 1953 session didn’t yield any satisfying masters, McPhatter put together a second group of Drifters around a pair of brothers, Gerhart and Andrew “Bubba” Thrasher, whom he knew from singing in church. Jesse Stone rehearsed the group extensively and wrote a new song, “Money Honey,” that would launch the group’s historic career after they returned to the studio in August.

Atlantic never expected to sell records to whites. They made records for blacks and sometimes even tailored pop material for the rhythm and blues market. Wexler, in fact, was looking for an r&b group to cover the latest Patti Page record, “Cross Over the Bridge,” when he stumbled across the label’s first great pop hit.

He took a Bronx vocal group that called themselves the Chords into the studio in March 1954. For the afterthought B-side, the group offered a swinging, almost jazzy, largely indecipherable piece of inspired lunacy called “Sh-Boom.” The B-side caught fire on the West Coast. The label stripped the Patti Page cover off the single—thinking to save it for later—rereleased the single, and quickly dumped off half the publishing for $6,000 to Hill & Range. The Chords version on the new Atlantic subsidiary label, Cat Records, hit the pop charts in June 1954. A week later, the cover version from the Canadian vocal group called the Crew Cuts charted. Although the Chords version made extraordinary inroads for an independent r&b record on the pop charts, winding up nicking the bottom of the Top Ten, the smooth, gleaming white version went all the way to number one and Atlantic, unfortunately, had kept only half the publishing. Best six grand Hill & Range spent all year.

While Atlantic was beginning to see some benefit from a subterranean shift in popular tastes as the market began to expand for rhythm and blues records, the company did not derive income from the sales of cover records. Neither did the artists. When r&b chart veteran LaVern Baker finally managed to land a record on the pop charts with “Tweedlee Dee” in January 1955, the plain white cover version by Georgia Gibbs that came out two weeks later outsold Baker’s smoking record. Baker couldn’t help holding a certain resentment toward Gibbs. She also couldn’t resist her little joke. Always a nervous flyer and headed out on tour, Baker took out flight insurance at the airport, named Georgia Gibbs the beneficiary, and sent her the insurance papers.

Ray Charles summoned the Atlantic chiefs to Atlanta in November 1954. He had been tooling around the South building his own band, learning to play them like an instrument, finding his sound. They say the crowds dancing to his band in tobacco barns raised so much dust from between the floorboards, partners couldn’t see one another. The Atlantic guys sent him material from time to time, but he liked little of it. Instead he was working on his own songs. The trumpet player in the band brought him a half-done piece based on an old gospel song and Charles put some finishing touches on the number and started playing it onstage, as he and his band continued a string of endless one-nighters with T-Bone Walker and Lowell Fulson. Since he didn’t have any dates in the New York area, but he had four songs rehearsed and ready, he told Ahmet and Jerry to meet him in Atlanta, when he came into the Peacock Room for two weeks.

Ertegun and Wexler went straight to the club from the airport. Even though it was afternoon, Ray and the band were set up on the bandstand. When Ahmet and Jerry stepped foot in the club, Charles knew they were there and sent the band straight into “I Got a Woman.” In a moment, they realized that Charles had coalesced all the elements they saw in him, pulled together the disparate forces within him, and found his voice. They booked time where they could find it—a local radio

station where they had to stop recording at the top of the hour while an announcer came in and read the news—but they left town with four tracks in the can, including “I Got a Woman.”

The single went number one R&B after it came out in January 1955, connecting Ray Charles for the first time across the country with black disc jockeys and audiences. They followed their best instincts with Ray Charles and left him alone. It was a novel a&r strategy, not widely practiced in the industry, and Atlantic was going to be rewarded, not with just another hit record, but also with an artist whose voice would reach multitudes. The records they were making were defining rhythm and blues, and rhythm and blues was spreading out on the nationwide record scene underneath them. With Ray Charles, they had the good sense to just let it happen.

*

Ahmet liked to record his songwriting demos in the Make-a-Record booth at the Times Square subway station.