Here Comes the Night (17 page)

*

Leiber and Stroller used their pen name on the songwriting credit, Elmo Glick, a Leiberesque contraction of the names Sammy Glick, from the novel

What Makes Sammy Run?

, and bluesman Elmore James.

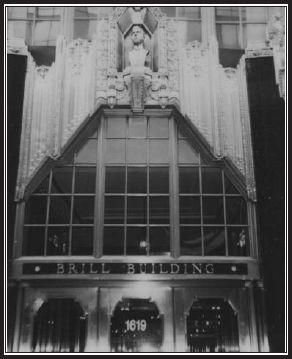

1619 Broadway

T

HE BRILL BUILDING,

an eleven-story office building at 1619 Broadway, was built by Abraham E. Lefcourt, a skyscraper builder who changed the face of New York. He originally intended the tower to be one floor taller than the Empire State Building, which would have made it the tallest building in the world, but the builder ran into financial problems and his real estate empire collapsed. The three Brill brothers, haberdashers who operated a store in the neighborhood for decades, took over the building in 1932, although Lefcourt left behind a bust of himself at the top of the building and, above the front door, a bust of his son Alan Lefcourt, who died a year before of leukemia. Like all the pluggers, Berns took the elevator to the top floor and worked his way down, going office to office selling songs.

The music business adopted the building in the early thirties. Old-line publishers like Irving Mills and Southern Music still kept offices there, and other relics of the swing era were listed in the building’s directory—from Duke Ellington to “Swing and Sway with” Sammy Kaye. Irving Ceasar, the old-timer who wrote “Tea for Two” and “Is It True What They Say about Dixie,” could be found in an office just down the hall from Leiber and Stoller, when he wasn’t at the racetrack. Amateur singers loitered outside on the sidewalk. Two restaurants flanked the lobby on Broadway, the Turf, where you had to push

past music business insiders such as Jackie Wilson or Brook Benton to get a drink at the bar, and Jack Dempsey’s, favored by the older crowd, watched over by the champ himself.

There were arrangers, copyists, bandleaders, song publishers, record labels, distributors. Recording studios were nearby in the bustling Midtown neighborhood. Colony Records was on the corner, where the latest records and hit sheet music were always available. This was the music business, baby.

While Berns was starting out down the street, the biggest and the best were at the top of their game at Forty-Ninth Street and Broadway. The Brill Building was only around the corner, but it was a long way from 1650 Broadway. This was the high-rent district of the music business, and the firms inside were the gold standards.

Songwriter Doc Pomus worked in a little cubbyhole in the penthouse office of the Brill Building. He wrote “Save the Last Dance for Me” late one night at his home on the back of his wedding invitation. Crippled by polio at age six, he never expected to get married and became a songwriter only reluctantly, after he gave up his career as New York’s first white blues singer. He cut “Heartlessly” for RCA Victor in 1955, and of all the thirty or so records he had out, he never had a shot like that before. Alan Freed slammed the big ballad nightly on WINS and the record exploded on jukeboxes. But RCA dropped the record. It was over like someone switched out the light. Pomus never knew why, although he suspected it might have something to do with the fact that the singer was a thirty-year-old, overweight Jew living in a fleabag hotel who couldn’t stand without crutches and leg braces.

Ray Charles recorded his “Lonely Avenue,” and the Atlantic guys, who knew Pomus from before there was an Atlantic, started feeding his material to Big Joe Turner, Pomus’s idol since he was a sickly kid listening to Turner sing “Piney Brown Blues” over the radio late at night. Big Joe did good with his “Boogie Woogie Country Girl.” Pomus first met Mike Stoller in Atlantic’s waiting room, where Stoller recognized

Pomus as the vocalist behind a hip radio commercial Pomus used to sing on Symphony Sid’s

Make Believe Ballroom

. Pomus struck up a friendly relationship with the two younger songwriters and, some months later, slipped Stoller a tape of a song he thought might be something for the Coasters, “Young Blood,” and shortly thereafter forgot he ever did.

Anyway, Pomus married actress Willi Burke in 1956 and they were returning from a honeymoon in the Catskills when Pomus stopped at a diner and absentmindedly checked the jukebox only to see a new single by the Coasters with a song called “Young Blood.” He watched carefully as the record loaded to play and saw the label spinning around reading “Leiber-Stoller-Pomus.” He pumped coins into a pay phone outside and reached Jerry Wexler at Atlantic, who told him the record was a smash and that he would wire Pomus a $1,500 advance. It was more money than Pomus had made all year.

Three years later, he sat at home alone in a postmidnight haze, smoking cigarettes and turning over the wedding invitation in his fingers. That afternoon, his songwriting partner, Morty Shuman, had played him a florid, flamenco-flavored melody and Pomus had already decided he wanted the lyrics to sound as if they had been translated from Spanish. He wrote long lines of percolating one-syllable words—“You can dance every dance with the guy who gives you the eye, let him hold you tight”—as he remembered sitting by himself on their wedding night and watching his bride dance with, first, his brother and, then, one friend after another. He couldn’t quite put all the pieces together, but he scrawled “Save the Last Dance for Me” across the top and went to bed.

Pomus and Shuman had written ten chart songs in 1959, more than anybody except Leiber and Stoller, who had twelve. In 1961, they wrote thirteen, more than anybody, period. After “Young Blood,” Pomus had determined that writing grown-up blues for adult singers such as Big Joe Turner and Ray Charles wasn’t going to buy the groceries for a newly

wedded family man and Shuman was going to guide him to the teenage market. Mort Shuman was a high school student to whom, at first, Pomus gave 10 percent simply to sit in the room while Pomus wrote, serving as kind of an instant test market. Slowly Shuman became more of a collaborator and their stuff started to get better. Shuman lived at home with his mother in Brighton Beach—his father drank himself to death around the time Doc got married. He took occasional philosophy courses at City College, made indecent proposals to black co-eds, drank wine, and slept on the subway home to Brooklyn. Shuman and Pomus made the rounds of the Brill Building publishers, often in company with Pomus’s wife, Willi—the hipster teen and his older, crippled songwriting partner with his blonde ingénue wife.

They landed at the Brill Building almost by accident. They started out at 1650 Broadway. Pomus met a former Arthur Murray dance instructor who had married a rich widow and needed a front so he could get away from the old dame. He loaned Pomus $10,000 of the lady’s money to start a record label. Pomus rented an office at 1650 Broadway and opened R&B Records (the name was his idea). When a group walked in off the street from Harlem wanting to audition called the Five Crowns, Doc and Morty found themselves interested in making records for real with this group, which revolved around lead tenor Charlie Thomas and shy, bass-voiced Benny Nelson. “Kiss and Make Up” in 1958 was a decent-enough record, and even started to take off in Pittsburgh, but the dance instructor’s widow figured out the charade and R&B Records was quickly no more. The Five Crowns found work. Manager George Treadwell hired the group to be the Drifters, and the Five Crowns started their career as the Drifters by recording “There Goes My Baby.”

Otis Blackwell used to come by the R&B Records offices. Pomus knew Blackwell from their days singing at blues joints in Brooklyn during the forties, long before Blackwell hit it big with Elvis Presley songs such as “Don’t Be Cruel” or “All Shook Up.” Blackwell wrote

the Little Willie John number “Fever,” and Peggy Lee had a big record with it. His latest was Jerry Lee Lewis—Blackwell wrote “Great Balls of Fire” and “Breathless.” He took Pomus and Shuman to meet Paul Case, the savvy professional manager of Hill & Range, the publishing firm that occupied the penthouse suite at the Brill Building.

Pomus and Shuman were signed to Hill & Range and the first assignment Paul Case gave them was a teen idol candidate from Philadelphia named Fabian. He had been discovered by his manager sitting on his front stoop minutes after his father had been taken away in an ambulance with a heart attack. He had no evident musical skills. His vocal range didn’t go much past four or five notes and his pitch was iffy, but he was a beautiful boy who looked the part. Case watched his effect on teen girls at record hops and thought there was gold there, if Pomus and Shuman could tailor some material that would, at least, downplay his insufficiencies. They wrote a string of successful hits for Fabian that launched him. They concocted a gimmicky rock and roll hit for Bobby Darin, “Plain Jane.” Case gave them more teen idols—James Darren, Bobby Rydell, Frankie Avalon. They wrote “Go Bobby Go” for Bobby Rydell, who didn’t like it, so they handed it to Jimmy Clanton as “Go Jimmy Go,” telling Clanton they wrote it for him.

Elvis Presley Music put Hill & Range in the penthouse of the Brill Building in 1956, when swing-era bandleader Tommy Dorsey choked to death in his sleep after stuffing himself full of Thanksgiving turkey, booze, and sleeping pills, leaving an unexpected vacancy that holiday season at the top of the Broadway office building. The music publishing firm occupied a lavish twelve-thousand-square-foot office, the walls decorated with dreary paintings by Bernard Buffet, the French artist whose career was sponsored by the Aberbachs, major collectors of modern art. Office wiseacres called the Picasso lithograph of mating doves “The Fucking Pigeons.”

With all their hits, Pomus and Shuman were rewarded with an eight-by-ten cubicle with a couple of chairs and an upright piano, and

a small window with a ledge. Pomus parked his family in an enormous Long Island home and took a room around the corner at the Hotel Forrest, where he stayed during the week. Damon Runyon Jr. lived in the penthouse. Surrounded by gamblers, con men, whores, and lowlifes of all kinds, Pomus held forth in the lobby nightly. Paul Case had introduced him to Phil Spector while the kid was still sleeping in Leiber and Stoller’s office. They wrote songs together in the hotel lobby and retreated to Doc’s room, where Doc played him his jazz records.

When a vocal group from Brooklyn called the Mystics turned up in the office looking for material, Morty recognized them from his old neighborhood. They tried out a song the pair had already written, “It’s Great to Be Young and In Love,” but Pomus wasn’t satisfied. He rewrote the entire lyrics, saving one line (

each night I ask the stars up above

), and gave them a new song, “Teenager in Love.” Gene Schwartz at Laurie Records, the group’s label, thought the song was too good for the Mystics and gave it instead to the label’s leading act, Dion and the Belmonts. Pomus and Shuman, chagrined, came up with another piece expressly for the Mystics, a nursery rhyme–like lullaby, “Hushabye.”

Three different versions of “Teenager in Love” climbed the U.K. charts and British television producer Jack Good decided to devote an entire episode of his weekly musical variety show,

Boy Meets Girls

, to the songs of Pomus and Shuman. Doc and Morty made the trip to London, where they were greeted like pop music royalty. In London, they ran into Lamar Fike, one of Elvis’s friends from Memphis on his way to Germany, where Presley was currently finishing his Army stint. Fike said he could get a song to Elvis. Neither Pomus nor Shuman gave that much of a chance, but Morty went into the studio and knocked out a piano and voice demo of a few songs. When Elvis got out of the army, he cut their “A Mess of Blues” at his first recording session. Paul Case gave them the next Presley single, which involved putting English lyrics to an old Italian ballad. Shuman wanted nothing to do

with something so cornball, but Pomus didn’t mind. He gave Presley “Surrender,” another number one.

Pomus and Shuman dashed off a couple of songs for Bobby Vee while staying at the Roosevelt Hotel in Hollywood, but Vee didn’t like them. Since they were in Hollywood, they took the songs to their old pal Bobby Darin, now a big movie star living in a Hollywood Hills mansion with his starlet wife, Sandra Dee. Darin took several passes at both songs, but never got them right. They handed the songs over to Paul Case when they returned to New York and he passed them along to another Hill & Range client. Elvis cut both “(Marie’s the Name) His Latest Flame” and “Little Sister” in a marathon all-night session in June 1961 in Nashville, at one point phoning Pomus and waking him up from his sleep to ask a question. It was the only time the singer and songwriter ever spoke and Pomus thought it was a prank.

Hill & Range founders Jean and Julian Aberbach were behind-the-scenes masterminds to the whole Elvis enterprise. Jean Aberbach was a protégé of the great Max Dreyfus—publisher of the Gershwins, Rodgers and Hart, and Cole Porter; and founding member of publishing rights group the American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers (ASCAP)—and Aberbach learned music business intrigue and chicanery at the feet of the master, the man who invented the game. Long before Presley was scouted by a Hill & Range operative named Grelun Landon in Tupelo, Mississippi, in May 1955, the Aberbachs made piles with Presley’s manager Colonel Tom Parker on partnership publishing deals with his clients Eddy Arnold and Hank Snow that were modeled after deals Dreyfus first constructed with Gershwin, Rodgers and Hart, and Porter.