Here Be Dragons (5 page)

Authors: Stefan Ekman

WHAT IS A FANTASY MAP?

A map is a symbolized representation of geographical reality, representing selected features or characteristics, resulting from the creative effort of its author's execution of choices, and is designed for use when spatial relationships are of primary relevance.

30

If this is how a map is to be defined, the maplike illustrations found in a vast number of fantasy works present a problem. Although they undeniably “[result] from the creative effort of [their authors'] execution of choices,” an overwhelming majority of them are

not

representations of “geographical reality.” Their “features or characteristics” bear little or no relation to anything in the actual world. They are simply not maps, as they violate the deeply ingrained notion that a map must in some way represent the world of the cartographer. Even the most concise definition I have found, that of American cartographers Arthur H. Robinson and Barbara Bartz Petchenik, ultimately falls back on this notion. To them a “map is a graphic representation of the milieu,” wherein the word

milieu

“connotes one's surroundings or environment in addition to its meaning of place.”

31

Cartographically, a fantasy map seems to be a contradiction in terms.

Actually, Robinson and Petchenik seem to have no problems with

maps of imaginary places, as they include them among their examples.

32

Historian Jeremy Black brings up the problem of mapping politics in maps of imaginary worlds, but he never questions their status as maps.

33

In his influential book

The Power of Maps

, map scholar Denis Wood similarly acknowledges the existence of

fictional

and

fantastic

maps.

34

In a later book, Wood discusses maps of imaginary places (mentioning, for instance, the maps of Middle-earth, Dungeons & Dragons, and the Marvel Universe) at some length, concluding that they illustrate how maps need not represent a part of the Earth's surface.

35

Consequently, fantasy maps are treated as maps here, with one important caveat. The difference between the map that graphically represents the milieu and a map of an imaginary place is one of priority: a map

re

-presents what is already there; a fictional map is often primaryâto create the map means, largely, to create the world of the map. (This is the case even though maps that are made to fit an existing literary work are by no means uncommon. Padrón includes the many maps of Hell that are based on Dante's

Divina Commedia

as examples of this phenomenon.

36

) Some points, then, on terminology before proceeding: First, the maps in the fantasy novels to be examined are not maps in the sense that they necessarily correspond to anything in the actual world. Drawing inspiration from Wood's terms, I refer to

fictional maps

and

fantasy maps

, where the former category includes any map that does not represent the actual world and the latter is a map of a fantasy world, generally found in a fantasy novel (although the term would fit maps from fantasy role-playing games equally well). Maps of the actual world are consequently

actual maps

. Second, to avoid suggesting that fictional maps in any way correspond to a position in the actual world, I say that they

portray

rather than

represent

something.

The status of the fictional map in relation to the text is in no way clear-cut, and various points of view yield different insights. In

Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation

, Gérard Genette uses the term

paratext

to refer to the various “verbal or other productions, such as an author's name, a title, a preface, illustrations” that accompany a text.

37

Whether they belong to the text or not, he explains, these productions surround and extend it. Genette mainly considers textual paratexts, but in his conclusion, he mentions some paratextual elements that he has not examined. Among these are “certain elements of the documentary paratext that are characteristic of didactic works” but that sometimes appear in works of fiction.

38

Genette's examples of such elements include fictional maps, for

instance Faulkner's map of Yoknapatawpha County and Umberto Eco's plan of the abbey in

The Name of the Rose

(1980).

It makes sense to regard a fantasy map as something that extends the fantasy text. The maps are generally not part of the narrative, in that they do not refer directly to any object in the text (with a few exceptions, such as Thror's Map in

The Hobbit

, which is also parenthetically referred to by the narrator

39

). Instead, they and the text both refer to the fictional world or to a part of itâthat is, to the story's setting. Thus, they become, in Genette's terminology, a

threshold

,

40

a liminal space between the actual world of the reader and the fictional (generally secondary; see

Table 2.2

) world of the fantasy story. The maps blur the distinction between representation and imagination, suggesting that the places portrayed are in fact representations of existing places. This suggestion would explain why fictional maps are usually considered to be maps, even though they do not share the actual maps' representing of the “milieu.”

Alternatively, fantasy maps can be interpreted as

docemes

. A doceme is defined by documentation-studies scholar Niels Windfeld Lund as “any part of a document, anything that can be identified and isolated analytically as part of the documentation process or the resulting document.” Moreover, Lund explains that although, for instance, a photograph can be a document in itself, if it is part of a newspaper article, it (as well as the article text) is only a docemeâ“[a] doceme can never be something in itself.”

41

Thinking of the fantasy map as a doceme puts a stronger emphasis on the relationship between narrative (text) and map. Rather than offering a threshold between fiction and reader, the map is part of the total fantasy document. Lund's observation that the doceme is part of

the documentation process

or

the resulting document

is also highly relevant. The map is not only one of several parts of the finished document; it can, as in the case of Stevenson's Treasure Island, be a central part of the creation process: according to Orson Scott Card, maps are basic to Card's world creation and provide him with story ideas;

42

Poul Anderson explains how, “[w]hen a story has an imaginary setting, I draw a map as part of the planning”;

43

and in a letter, Tolkien relates how he “wisely started with a map, and made the story fit (generally with meticulous care for distances).”

44

Three authors do not, of course, represent a genre, but they all point in the same direction, and Tolkien proceeds to explain why the map's priority is important: “The other way about lands one in confusions and impossibilities, and in any case it is weary work to compose

a map from a story.” In the same letter, he also apologizes for “the Geography” and acknowledges how difficult it must have been to read

The Lord of the Rings

proofs without maps. In other words, Tolkien felt the map doceme to be necessary both during the documentation process and when reading the resulting document.

In the two discussions on maps that follow, we can see how fantasy maps can be fruitfully interpreted as both paratexts and docemes. The two perspectives are not mutually exclusive but relate the map differently to the text. Constituting thresholds between the actual and fictional worlds, they are also an essential part of the document that is the fantasy book.

A SURVEY OF FANTASY MAPS

To take a quantitative approach to the fantasy map, I carried out a survey of two hundred randomly selected fantasy works and looked at the maps I found in them. This section is devoted to a presentation of the survey results, examining the maps' general features as well as the types of map elements found, and discussing what these findings can tell us about specific settings and the genre as a whole. The small number of works in the sample, and the low proportion of maps among those works, resulted in fairly large margins of error, but the results still indicate some interesting features of fantasy maps. (A more thorough presentation of the survey method and the assumptions on which it is based, along with the statistical method used for calculating margins of error, can be found in

appendix A

; a list of works in the sample can be found in

appendix B

.)

The Prevalence of Maps

Here is the most basic question: how common is it for fantasy novels to contain at least one map? Of the two hundred novels in the sample, sixty-seven (34 percent) contained one or more maps. In terms of the entire genre, this means that no more than 40 percent and possibly as few as 27 percent of all fantasy novels actually contain any maps. In other words, maps are not the compulsory ingredients they are widely held to be. The main explanation for this apparent lack of maps has to do with setting. The sampling frame (and thus the sample) comprises the entire genre, high fantasy as well as low, but maps are much more common in fantasy set in a secondary world. In the sample, of the sixty-seven novels that have maps, only six contain maps portraying the primary world

(corresponding to 3 to 18 percent of all novels with maps), and these are all set in historic or prehistoric times. While there are low-fantasy works in contemporary settings that have maps, their numbers are small enough not to crop up in the sample (constituting fewer than 5 percent of all maps and less than 2 percent of the genre). Examples include Alan Garner's

The Weirdstone of Brisingamen

(1960), with a map of the area around Macclesfield in Cheshire; Neil Gaiman's

Neverwhere

(1996), with a map of the London Underground; and Charlie Fletcher's

Stoneheart

(2006), with a map of central London.

45

As I had no data on the general distribution of high fantasy to low in the sample, I was unable to pursue this matter further (see also

appendix A

).

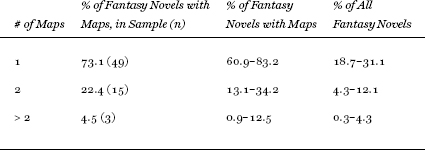

2.1. HOW MANY MAPS DO FANTASY NOVELS CONTAIN?

N = 67

Related to the question of how prevalent maps are in fantasy novels is the question of how

many

maps a fantasy novel contains. While three quarters of the novels with maps contained only a single map (roughly between 20 and 30 percent of the genre), slightly over one fifth had two maps, and novels with three, four, and six maps also appeared (see

Table 2.1

). In most cases (fourteen out of eighteen), the additional maps provided one or more large-scale views of one or more areas (in four cases, this included a city map). Of the remaining four cases, two had floor plans for buildings, one had maps of two different continents, and one mapped the area's political and physical features on two separate maps. The main reason for including more than one map, in other words, seems to be to provide a general, small-scale map and a larger-scale map of an important setting: a country, province, or city, for instance. The maps in

The Lord of the Rings

provide an example of this tendency. A large-scale map of the Shire, a small-scale map of the entire western Middle-earth, and a medium-scale map of the area around Gondor and Mordor are included,

illustrating how the story's quest-narrative is built around long journeys across the world, but also requires detailed maps for locales where central events are set. (Tolkien's large-and small-scale maps are discussed in detail later in this chapter.)

When examining the features of the fantasy map, I use as my sample the ninety-two maps found in the survey. In five cases, the same map (or similar versions of the same map, when, for instance, different artists have drawn maps for books with the same setting) appears in two or more books. Such maps have been counted as separate instances, however, partly because the efforts of different mapmakers may result in very different renditions of the same location (as can be observed from the maps in the Conan books in the sample

46

), but mainly because they constitute docemes in different documents.

General Map Features

:

Subject, Orientation, Surround Elements

Only six of the novels with maps portray a primary-world setting. These six novels contain thirteen of the ninety-two maps, and even though there are fantasy books that have maps of primary-world cities, no such maps can be found in the sample, confirming how rare such maps are (corresponding to less than 4 percent of all fantasy maps). The vast majority of maps portray a secondary world or an area in a secondary world (almost four fifths of the sample, or between 68 and 86 percent of all fantasy maps). Of the remaining maps, about 5 percent (2 to 12 percent) portray an imaginary city, either in a secondary world or set in the primary world (an example of the latter is the city of Ys, a map of which appears in Poul and Karen Anderson's

Dahut

[1988]), and 2 percent (0.3 to 8 percent) are plans of buildings or building complexes.