Her Highness, the Traitor

Read Her Highness, the Traitor Online

Authors: Susan Higginbotham

Copyright © 2012 by Susan Higginbotham

Cover and internal design © 2012 by Sourcebooks, Inc.

Cover design by Susan Zucker

Cover image © Cloudniners/istockphoto; Stephen Mulcahey/Arcangel Images

Sourcebooks and the colophon are registered trademarks of Sourcebooks, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems—except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews—without permission in writing from its publisher, Sourcebooks, Inc.

The characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious and used fictitiously. Apart from well-known historical figures, any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental and not intended by the author.

Published by Sourcebooks Landmark, an imprint of Sourcebooks, Inc.

P.O. Box 4410, Naperville, Illinois 60567-4410

(630) 961-3900

Fax: (630) 961-2168

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Higginbotham, Susan.

Her highness, the traitor / Susan Higginbotham.

p. cm.

(pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Grey, Jane, Lady, 1537-1554—Fiction. 2. Women—England—History—Renaissance, 1450-1600—Fiction. 3. Great Britain—History—Tudors, 1485-1603—Fiction. 4. Great Britain—Kings and rulers—Fiction. I. Title.

PS3608.I364H47 2012

813’.6—dc23

2012003465

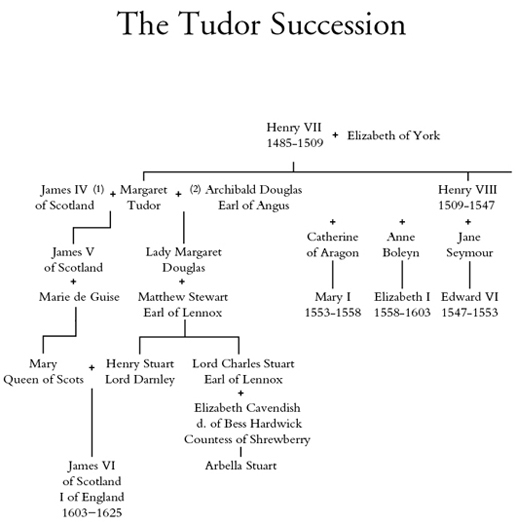

The Royal Family

Edward VI, King of England.

Mary, his half sister, later Queen of England.

Elizabeth, his half sister, later Queen of England.

Catherine Parr, Queen of England; sixth wife of Henry VIII, later married to Thomas Seymour.

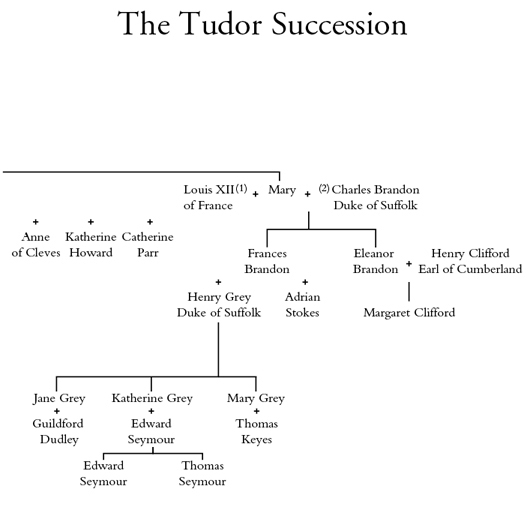

The Greys

Henry Grey, Marquis of Dorset, later Duke of Suffolk.

Frances Grey (née Brandon), wife of Henry Grey, Marchioness of Dorset, later Duchess of Suffolk; niece to Henry VIII.

Jane Grey, daughter of Henry and Frances Grey, later married to Guildford Dudley.

Katherine (“Kate”) Grey, daughter of Henry and Frances Grey.

Mary Grey, daughter of Henry and Frances Grey.

The Dudleys

John Dudley, Viscount Lisle, later Earl of Warwick, later Duke of Northumberland.

Jane Dudley (née Guildford), wife of John Dudley, Viscountess Lisle, later Countess of Warwick, later Duchess of Northumberland.

John (“Jack”) Dudley, son of John and Jane Dudley, later Earl of Warwick, later married to Anne Seymour.

Ambrose Dudley, son of John and Jane Dudley, later married first to Anne “Nan” Whorwood, then to Elizabeth Tailboys.

Robert Dudley, son of John and Jane Dudley, later married to Amy Robsart.

Guildford Dudley, son of John and Jane Dudley, later married to Jane Grey.

Henry (“Hal”) Dudley, son of John and Jane Dudley, later married to Margaret Audley.

Mary Dudley, daughter of John and Jane Dudley, later married to Henry Sidney.

Katheryn Dudley, daughter of John and Jane Dudley, later married to Henry, Lord Hastings.

Andrew Dudley, younger brother of John Dudley.

Jerome Dudley, younger brother of John Dudley.

The Seymours

Edward Seymour, Earl of Hertford, later Duke of Somerset (“the Protector”). Brother to Jane Seymour, third wife of Henry VIII.

Anne Seymour, wife to Edward Seymour, Countess of Hertford, later Duchess of Somerset.

Anne Seymour, daughter of Edward and Anne Seymour, later married to Jack Dudley, known as Countess of Warwick after October 1551.

Jane Seymour, daughter of Edward and Anne Seymour.

Edward Seymour, son of Edward and Anne Seymour, later Earl of Hertford.

Thomas Seymour, later Lord Sudeley (“the Admiral”), younger brother to Edward Seymour, later married to Catherine Parr.

Others

John Aylmer, tutor to Lady Jane Grey.

Katherine Brandon (née Willoughby), Duchess of Suffolk; widow of Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk; stepmother of Frances Grey; later married to Richard Bertie.

Bess Cavendish, friend of Frances Grey, later known as Elizabeth Talbot, Countess of Shrewsbury.

Susan Clarencius, lady-in-waiting to Mary.

Ursula Ellen, gentlewoman to Jane Grey.

George Ferrers, courtier and Lord of Misrule.

Henry Fitzalan, Earl of Arundel, nobleman.

Maudlyn Flower, gentlewoman to Jane Dudley.

Edward Guildford, father of Jane Dudley.

Joan Guildford, wife of Edward Guildford, stepmother to Jane Dudley.

Francis Hastings, Earl of Huntingdon, father-in-law of Katheryn Dudley.

Henry, Lord Hastings, son of Francis Hastings, husband to Katheryn Dudley.

George Medley, half brother to Henry Grey.

Elizabeth Page, mother of Anne, Duchess of Somerset.

William Paget, royal councilor.

Anne Paget, wife of William Paget.

Elizabeth Parr, Marchioness of Northampton.

William Paulet, Lord St. John, later Marquis of Winchester.

Adrian Stokes, master of the horse to Frances Grey, later her second husband.

Elizabeth Tilney, gentlewoman to Jane Grey.

Anne Throckmorton, friend of the Greys.

Anne Wharton, lady-in-waiting to Mary.

Jane Dudley

January 1555

If there is an advantage to dying, it is this: people humor one’s wishes. I could ask for all manner of ridiculous things, and I daresay someone would try to oblige me, but instead I simply call for pen and paper.

“Here follows my last will and testament, written with my own hands,” I begin, and then I stop, frowning. I am not learned in the law, and the thought occurs to me that perhaps I should give up my task and call in someone who is. But he would charge for it, and that fee would make my children, who have lost so much already, that much the poorer. So I press on. I can say what I need to say as well as any lawyer can, though I might not be as verbose about it. If these last few months have taught me anything, it is how to fend for myself, which is more than I can say for some women I know.

But there is a phrase I am searching for. What is it?

Being

in

perfect

memory

, of course. I smile to myself, for although I have forgotten that phrase, there is not much else I have forgotten.

January

1512 to January 1547

I was not born to high estate. My father, Edward Guildford, was only a knight—and he was not even that when I was born, but a mere squire, albeit one high in the young king’s favor. It was owing to this royal esteem that one chilly day in January 1512, my father strode into our hall at Halden in Kent with a black-haired boy in tow. “This is John Dudley, Mouse,” Father said, using the pet name I had been given to distinguish me from my stepmother, Joan, whose name was sufficiently close to mine as to cause confusion sometimes. “He is to be my ward—that is, in my care—now that his father is dead and his mother’s remarried. He’ll be staying here a long time.”

John, who was seven years of age to my three (almost four, as I liked to point out), executed a respectful bow, but did not match my stepmother’s welcoming smile. “You look cold, John,” my stepmother said then, her voice lacking its natural warmth. “Why don’t you sit by the fire?”

It was an order rather than a suggestion, and the boy said, “Yes, mistress,” and obeyed. His voice was not a Kentish one, even I at my young age could tell.

“He seems very ill mannered,” my stepmother said when the boy was out of earshot.

“He’s coming among strangers, and he’s tired. He’s a London boy, don’t forget, not used to riding.” My father chuckled. “Stared at my horse as if he were at the menagerie at the Tower. I had him take the reins for a time while coming here, though, and he did quite well. He’s sharp.”

“Aye, like his father. And look where that got

him

, speaking of the Tower.”

“Where’s that, Mama?” I could not resist asking. “What tower?”

“Never you mind,” said my stepmother briskly as my father gave her what I had begun to recognize as a meaningful look. I was a quiet child, which meant adults often said interesting things in my presence they might have avoided saying in front of a more talkative girl, but sometimes to my disappointment they remembered themselves. Pitching her voice in a manner that informed me that future comments would not be welcome, she said to my father, “How much does he know of all that, by the way?”

“Most all, I fear. Some of the neighbors talked before they stopped speaking to the family altogether, and he figured out the rest for himself. He’s sharp, as I said.”

“Oh.” My stepmother’s voice softened. “Poor lad.” She glanced at me. “Jane, why don’t you join Master Dudley by the fire?”

I obeyed. John was sitting on a bench and staring into the flames. Shy as I was, I was being brought up to converse properly, as became a well-bred young lady. “Hello,” I said brightly.

John looked at me with apparent reluctance, though in my opinion, I was at least more interesting than the fire, crackle as it might. “They called you ‘Mouse’ just now,” he said with the air of one feeling bound to say something. “That’s a strange name.”

“That’s just what they call me here. My real name is Jane.” I paused. “Jane and John. They sound almost alike.”

John grunted.

“I have my own pony,” I went on, undaunted. How I had forgotten to mention this to John immediately I had no idea, for there was no creature I loved more than my new pony, which I was just learning to ride. I’d tried my best to let everyone in Kent know of my new acquisition. “Father said you don’t know how to ride yet.”

“No. Why should I? I’m from London.”

I did know something about London. Father was often at the king’s court there. But I didn’t know all that much. I contemplated this apparently horseless place for a time before asking, “How do you go places there? Walk?”

The boy gave me a pitying look for my ignorance. “Just for short distances. People do ride, especially if they’re coming in or out of the country, but if you’re traveling from one part of London to another, it’s best to take a boat down the Thames.”

“Really?”

“My father used to take me all of the time before he died.”

“My mother’s dead,” I offered companionably. “She died the same day I was born.” (I thought at the time only that this was rather an interesting coincidence.) “They say she got sick. What did your father die of?”

“They cut off his head.”

I stared at him in bewilderment. I vaguely knew that men who did wrong things could get hanged, though I had never seen such a dreadful sight. But cutting a man’s head off? “Like a

chicken

?”

“Yes.”

I placed my hands on my neck and determined that losing one’s head would not be an easy accomplishment. “But why?”

“Mouse,” said my father, putting his hand on my shoulder and looking at John apologetically. “That’s enough questions for now. Your mother needs you to help her with—well, she needs you to help her with something.”

“Yes, Father,” I said, but I could not resist looking back at the boy as I scurried away. I had good reason to look back, after all; without knowing it, I had met my husband.

No, I was not born to high estate, and neither was my husband, the eldest son of a man who had been executed as a traitor. The titles we held were gained, and will die, all in a single generation. Yet if we were upstarts, we were no different from many others of our day. Dukes, earls, even queens—the court of Henry VIII was plentiful with those who had owed everything to one man, and in January 1547, five-and-thirty years after little John Dudley entered my life, that man, King Henry, lay dying at Whitehall. Henry VIII was an upstart in his own way, as well: his dynasty had sat on the throne for only two generations.

Upstart he might be, but I could not remember another king; I’d been but a babe in arms when Henry VIII came to the throne. I had known all six of his queens, if only well enough to bend a knee in some cases.

I mused upon this as I made my way from the queen’s side of Whitehall, where I had been attending the sixth and last of the king’s wives, Catherine Parr. There was no sign here that anything was amiss: meals were still being brought into the sick man’s chamber, accompanied by the sounds of trumpets. They would stay in the chamber for a decent interval, I supposed, before being brought out and distributed to the poor, who surely by now must have been wondering about all of this extra bounty they were receiving.

As I had hoped, my husband was inside the chamber we had been allotted at court. He rose from the desk at which he had been working and kissed me. “What brings you here?”

“I came to check on the king’s health.”

“Did the queen send you?”

“No, but I expect she will be glad to hear a report.”

“Then you must keep this secret, my dear, at least for a little while longer. King Henry is dead. He’s been dead for two days.”

I stared. “Why has no one been told?”

“The Earl of Hertford wished there to be no difficulties until King Edward was brought to Westminster. He, of course, has been told, along with the lady Elizabeth. The earl brought the news himself. Tomorrow it will be announced in Parliament.”

King

Edward.

It seemed a strange title for the nine-year-old I’d known since he was christened, whose mother’s funeral procession I’d ridden in. “Why was the queen not told? Why not the lady Mary?”

“They will be, very shortly.” My husband gave an uneasy cough. “I suppose Queen Catherine is expecting to be made regent.”

“Yes.”

“Then she will be disappointed, I fear. The king did not wish a woman—even a woman as able as the queen—to have the rule during the king’s minority. Don’t glare at me so, my dear. I am only the messenger. In truth, the council won’t have the rule of England either, not completely anyway. The council has agreed. There will be a protector.”

For a moment, I paused to admire the industriousness of the men who had settled all of this in just two days, while keeping up this façade of a living king. But I knew my chronicles. I frowned. “A protector?”

For the first time, my husband smiled. “Shades of Richard III! And yes, it is to be an uncle. But Hertford has no kingly ambitions, and it’s wise to have a single man in charge, even though he will be answerable to us on the council. And in any case, it’s a different world now than it was in 1483.”

“Well, it is that,” I conceded. I sighed, thinking how disappointed the queen would be not to be named regent for the young king. She’d been closer to him than any of the other queens, for Jane Seymour, Edward’s mother, had died soon after giving birth, the good-natured Anne of Cleves had lasted only a few months as queen, and poor Katherine Howard had been badly in need of a wise mother herself. Catherine Parr had been on good terms with all three of King Henry’s children—no easy task, as each was as different as their respective mothers. Surely she had deserved the honor of a regency after putting up with her increasingly lame and ill-tempered royal husband. Worse, Anne Seymour, Countess of Hertford, was completely insufferable. Being the protector’s wife could make her only more so. “What of Thomas Seymour?” He was the younger brother of Edward Seymour, Earl of Hertford; the two were Jane Seymour’s brothers. “Is he to have a role in all of this?”

“Something, I’m sure.” My husband yawned. “That’s to be discussed. These things take time.”

I stared out the window, my mind still trying to adjust itself to an England without Henry, who’d reigned nearly eight-and-thirty years, nearly as long as I had been alive. Softly, for I knew I was treading on delicate ground, I asked, “John, did you ever hate him for what he did to your father?”

“I never really thought about it.” My husband tipped my chin up gently and brushed his lips against mine. “I’ve got some time to spare before I return to the council. Do you have to hurry back to the queen?”

I smiled. It was not uncommon of my husband to avoid talking about a topic by making love to me. It was a tactic that might have been employed more often than I realized, and generally with success, for I had borne him thirteen children.

***

To a man’s eyes, I must have looked seemly enough as I returned to the queen’s lodgings at Whitehall. To a woman, it was obvious that unskilled hands had put me back into my clothes; all my fastenings were slightly awry. I hoped I had sent John back to his council meeting in somewhat better repair, though he had servants nearby who would probably step in to make him presentable.

Anne Seymour, Countess of Hertford, gave me a knowing look as I entered the outer room of the queen’s private chambers. The queen was in an inner chamber attending to business, it being the time of the day when she did this, but most of the other great ladies of England were here: the lady Mary, the new king’s eldest sister; the lady Frances, King Henry’s niece; a dozen or so others. I had known them all for years: together we’d buried Jane Seymour; greeted Anne of Cleves; watched helplessly as poor Katherine Howard giggled and flirted her way to the scaffold; speculated on who would be the king’s sixth, and it would prove, final, bride.

“Did you hear anything, Lady Lisle?” asked the lady Mary. Just shy of her thirty-first birthday, she was still reasonably attractive, despite her voice, which was oddly gruff for a woman’s.

I quaked at lying to a princess, but I did it anyway. “I have heard nothing new, Your Grace,” I said smoothly, sensing Anne Seymour’s eyes upon me. If I knew, she must certainly know, as well; her husband would no more leave her out of his confidence than mine would me. “I saw my husband, but he could tell me nothing more than that the king was doing poorly.” That, I consoled myself, could be viewed more as a gross understatement than as an outright lie.

“I can’t believe they have told us nothing. I know my father wished to make his peace with the Lord in private, but he is dying, for mercy’s sake! I simply cannot fathom that he would not want his queen or his children by his side.” Mary’s thin face hardened. “I am not putting up with this lack of communication any longer. When the queen finishes her business, we are going to go to the king’s lodgings togeth—”

A knock sounded upon the door, and a grave-looking man entered the room. “My lady,” he said, kneeling to Mary. “I am grieved to tell you that His Highness King Henry has departed from this life.”

Mary closed her eyes, then opened them again. What went through her head? After King Henry had repudiated her mother, Catherine of Aragon, and married Anne Boleyn, he had treated Mary horribly, declaring her a bastard. Only in the past several years had she been treated as a princess ought to be. Even after that, her father had been lacking: he’d not made a suitable marriage for her, so she was a maid at an age when many women were mothers ten times over; he’d not given her a household of her own, but seen fit to subsume hers within the queen’s. Her voice gave nothing away. “Has the queen been told?”

“Yes, my lady. She is being brought the news as we speak.”

“When did my father die?”

The man bowed his head even farther, perhaps as much out of caution as respect. “The king died two days before, my lady. Parliament will be informed tomorrow morning. The Earl of Hertford is aware that your ladyship might find the delay unsettling, and he has given me a letter explaining why he acted as he did.”