Henry VIII's Last Victim (39 page)

Read Henry VIII's Last Victim Online

Authors: Jessie Childs

In the summer of 1545 Surrey decided that he needed a more imposing coat of arms to fit in with the Surrey House aesthetic. He experimented with various quarterings, including those of Edward the Confessor, Geoffrey Plantagenet, Count of Anjou, and even, it seems, those of his mythical hero Lancelot du Lac. According to his sister, Surrey had over seven rolls of heraldic devices.

8

By the beginning of August he had made up his mind and summoned England’s chief herald, Christopher Barker, for official approval. Unfortunately Barker was not happy with Surrey’s shield. In particular he seems to have objected to the Anjou quarter. He probably also queried Surrey’s use of St Edward’s arms, though he may not have specifically forbidden them. Surrey returned to the drawing board, took out the Anjou quarter, but retained the arms of Edward the Confessor as he had a legitimate claim to them through his Mowbray ancestors.

9

This seemingly innocuous decision would prove a fatal error of judgement.

On 23 April 1545 Surrey attended the Chapter of the Order of the Garter at St James’s Palace.

10

It was an occasion of heightened solemnity, for it was rumoured that Francis I of France was ready to avenge the loss of Boulogne. Not only was he said to be sending forty thousand soldiers to besiege the town, but he was also planning to hamstring Henry VIII’s defences by invading England from the North with the help of his Scottish allies and by blockading the Channel with a great fleet that he was amassing at Le Havre.

Henry determined to meet the threat head on. Surrey and the rest of the nobility returned to their counties to muster men and collect taxes. In addition to levies and subsidies, merchants and landowners were expected to contribute to a loan called the Benevolence. It was anything but; an alderman who refused to pay was sent to the borders, where he was subsequently captured by the Scots.

11

Henry VIII’s three commanders from the previous year were entrusted with the security of England’s shores. The Duke of Norfolk guarded the East Anglian coastline, the Duke of Suffolk the South-East, and Lord Russell the

West. The King himself took personal command of the navy in Portsmouth. Surrey had been earmarked for the defence of Boulogne, but before he set sail he rode south to serve as liaison officer to Henry VIII and John Dudley, who as Lord Admiral, occupied Spitsand on the Solent with a fleet of sixty ships.

On 18 July 1545 the French Armada

appeared on the horizon. It comprised two hundred and thirty-five ships, far more than the Spanish would put out in 1588, and four times the number of the English fleet. However the English, protected by the shallows and swirling currents of the Solent and covered by the guns of the forts and blockhouses behind them, held the strategic advantage. For the next few days Surrey dashed back and forth exchanging messages between Henry VIII at Southsea Castle and the Lord Admiral aboard the

Great Harry

. ‘I would,’ Dudley assured his King, ‘for my own part little pass to shed the best blood in my body to remove them out of your sight.’

12

But it was all bluster. Henry VIII ordered Dudley to hold position. The French tried to lure him out by invading the Isle of Wight. If the King was tempted, the vagaries of wind and current forestalled a general engagement. Most of the ships that were lost were victims not of artillery, but of human error and misfortune. Francis’ first flagship had caught fire in Le Havre; its replacement sprang a leak and had to be run ashore. The fate of Henry VIII’s old warship, the

Mary Rose

, is the saddest of all. Someone forgot to close the gunports so that when the dangerously overloaded ship began to heel as she turned in the wind, water flooded the ports taking down the ship and over four hundred men with her. By mid-August the French Admiral, Claude d’Annebault, admitted defeat. With his fleet riddled with plague, he raised anchor on 16 August and sailed back to France.

13

Francis I’s proposed invasion from the North never amounted to much either, but it was calamitous for the Scots. Henry VIII vowed revenge and in Edward Seymour, Earl of Hertford, he had a willing and ruthless instrument. In the space of two weeks Seymour ‘burnt, razed and cast down’ towns, abbeys, hospitals and a total of two hundred and forty-three villages.

14

That just left Boulogne. Francis I, it was said, ‘hath so much spoken of Boulogne that he will have [it] and it hath been so noised in the world that in Boulogne consisteth now all his reputation, as he taketh it.’

15

By mid-August Thomas Poynings, the Captain of the English garrison at Boulogne, reported that twenty thousand French footmen, one thousand horsemen and twelve thousand sappers were

encamped opposite the town with more on their way. By contrast, the whole garrison at Boulogne, including sappers, clerks, bakers, brewers and other labourers numbered well under ten thousand.

16

Hundreds had died of the plague or been sent home and those that remained lacked munitions, armour and provisions.

In response to the crisis, Surrey had left Portsmouth for Kenninghall at the end of July. Within two weeks he was ready to cross the Channel with four thousand men from East Anglia and a further thousand drawn from the London musters. This was the vanguard of the army sent to reinforce Poynings. The Duke of Suffolk, who was due to leave shortly with the rest of the army, would assume overall command and Surrey would captain the vanguard.

17

However, an extraordinary sequence of events soon presented Surrey with an even greater opportunity to shine.

On 18 August Poynings died of ‘the bloody flux’. Four days later the Duke of Suffolk also died.

18

The Captaincy of Boulogne then passed to Lord Grey of Wilton, who had hitherto served the King as Captain of all the ‘crews’ within the marches of Guisnes and Calais. Surrey was ordered to fill Grey’s vacancy, but only days later Henry VIII changed his mind. Grey was told to resume his old post and Surrey, whose desire ‘to see and serve’ had already been noted by the King’s Secretary William Paget, was promoted to the Boulogne command.

19

Unlike his predecessors, who had only had the charge of the town, Surrey was also given ultimate responsibility for all English operations across the Channel. There could be no greater indication of Henry VIII’s unique estimation of Surrey at this time. Only three years earlier the King had refused to appoint Henry Clifford, Earl of Cumberland, as Lord Warden of the North Marches because ‘we think him to be yet of too few years for that office’.

20

Clifford had been twenty-five, only three years younger than Surrey was now, and yet Henry VIII appeared to have no qualms about entrusting Surrey with the greatest position of honour in his army. On the last day of August the Privy Council wrote to Surrey informing him of his appointment and on 3 September 1545 it was confirmed by letters patent. He was now Lieutenant General of the King on Sea and Land for all the English possessions on the Continent.

21

Boulogne was in poor shape after the battering it had received the previous year. The infrastructure had to be completely overhauled, the

houses needed rebuilding, the sanitation was poor and communications had to be revived. To the dismay of his more reform-minded friends, Surrey even erected an altar in the church. One of the earliest sets of instructions he received from the Privy Council concerned the imposition of order and the reduction of waste. He was told ‘to send away all sick and maimed men’, to launch an investigation into any malpractices committed by the head officers and ‘to rid all harlots and common women out of Boulogne’.

fn3

,

22

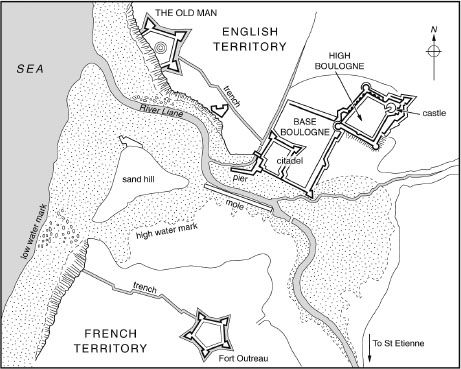

The town’s fortifications were crucial to the retention of Boulogne. There were three main strongholds. First was the bastioned watchtower, which stood on a cliff overlooking the Liane estuary and was known to the English as ‘the Old Man’. A little downstream was Base Boulogne, which controlled the harbour, and leading off from its north-east tower

was High Boulogne, where the castle stood and the main garrison was quartered. Surrey’s predecessors had already begun to re-fortify these sections and re-establish the lines of defence between them. Surrey consolidated and expanded their work, overseeing new ditches, trenches, gun-platforms, bulwarks, bastions and jetties.

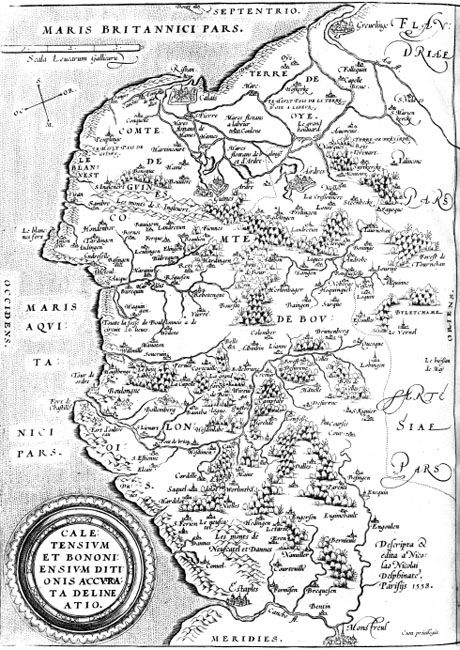

Map of the Pas de Calais by Nicholas de Nicolay, 1558

By the end of Henry VIII’s reign Boulogne could boast an elaborate network of fortifications, characterised by the short, squat structures and angled bastions pioneered by the Italians. These ‘modern’ defences were a direct response to the recent improvements made in artillery and were far better at absorbing, and directing, cannon fire than the high-walled medieval castle. Surrey was by no means responsible for all the defences erected at Boulogne and, as he readily admitted, there was still much to be done by the end of his tenure, but the progress made under his watch was crucial. Indeed he assumed such an active role in the town’s defences that he clashed with John Rogers, the surveyor of the town, whose plans were as precious to him as any artist’s work-in-progress. ‘Your Lordship knoweth that the man is plain and blunt,’ Surrey had to be reminded, but he ‘must be borne withal as long as he is well meaning and mindeth the service of the King’s Majesty.’

23

It was not enough just to defend Boulogne from a direct assault; the town also had to be able to receive supplies. As the French controlled the outlying territory and were able to intercept any convoys travelling overland from Calais and Guisnes, the only viable supply line was from the sea. It was vital, therefore, that Surrey guaranteed protection to the ships entering and leaving the haven. The French commander, Marshal du Biez, who had defended Montreuil so effectively the previous year, was equally determined that Surrey should not. He had nearly finished work on Fort Outreau, an impressive pentagonal fortress built on the high ground opposite Base Boulogne across the River Liane. Its guns were not within accurate range of the town but its presence so close to the harbour was alarming, especially as du Biez was also setting up other strongholds along the coast and further inland.

24

Surrey’s options were therefore limited. The great army that was supposed to have been sent over with Suffolk had been stayed on his death.

25

If Surrey were to attempt anything major against the French, he would be outnumbered and outgunned and the town would be left vulnerable. But if he sat back and did nothing but improve his own defences, the French would be free to work on their own fortifications

and threaten his supplies. He therefore resolved upon a number of short, sharp sallies against the convoys sent to sustain the French works with materials and provisions from the south. In this, he was remarkably effective.

Among his many successful raids was the burning of Samer ‘and all the country thereabout’, the ambush of a French force around St Etienne – ‘we drove them from place to place to the Sandhills and so from hill to hill to Hardelot’ – and the putting to flight of forty French supply ships, seven of which were captured – ‘whereby, besides the ruin of their horsemen and footmen by the extremity of the weather, their whole purpose is for this present disappointed.’ Each triumph was joyfully narrated by Surrey in the glossy chivalric language that appealed to the King: ‘the cavalry offered the charge’; the enemy were ‘upon the spur’ and ‘well dagged with arrows’; ‘Francis Aslebye, that hurt Mons. d’Aumale break his staff very honestly’; ‘Mr Marshal very honestly and hardily brake his mace upon a Frenchman; Mr Shelley brake his staff upon a tall young gentleman of Monsieur de Botyer’s band and took him prisoner; and in effect, all the men at arms of this town brake their staves’.

26