Henry IV (47 page)

Authors: Chris Given-Wilson

It was widely believed that Hotspur was acting in collusion with Glyn Dŵr and Edmund Mortimer, an impression not dispelled by the coincidence of timing between his arrival from the north and Owain's march down the Tywi valley at the beginning of July.

17

On the other hand, the fact that Glyn Dŵr was marching westwards towards Pembrokeshire during the second week of July,

away

from the English border, indicates either that

something had gone awry with their plans or that they were predicated not on a rendezvous but on diversionary activity.

18

Hotspur did, however, meet up with his uncle Thomas, earl of Worcester, Prince Henry's governor and second-in-command of his army. Worcester's decision to join his nephew was evidently not a spur of the moment decision.

19

Like Hotspur, he may have resented having to cede control of operations in Wales to the sixteen-year-old prince. As Hotspur led his troops towards Shrewsbury, Worcester slipped away to the north of the town; by 20 July at the latest he had joined the rebel army, taking with him many of the 260 men-at-arms and archers he had retained for the prince's campaign and perhaps other disaffected soldiers as well.

20

Yet there was one eventuality which Hotspur and Worcester had overlooked: the arrival in the Midlands of the king. Since his wedding in February, Henry had remained close to London, staying mainly at Eltham and Windsor, keeping in touch with the Anglo-French negotiations at Leulinghem. These were concluded with a truce on 27 June.

21

A few days before this Henry had written to inform Northumberland that he did not plan to come north for the anticipated battle against the Scots at Cocklaw. The earl was probably relieved to hear this, and when he replied to Henry on 26 June from Heelaugh (Yorkshire), it was not to try to change his mind but to request money with which to pay his own troops; indeed Walsingham claimed that Northumberland discouraged Henry from coming north, since it would not be advisable for him to ‘desert his country’.

22

Yet within a day or two of receiving the earl's letter, Henry had changed his mind,

presumably as a result of the conclusion of the French negotiations.

23

It was certainly a hasty decision, leaving him no time to raise an army of any size. On 1 July he was still in London. By 9 July – the day Hotspur arrived at Chester – the king had reached Higham Ferrers (Northamptonshire), whence he wrote to London asking the council to send Prince Henry £1,000 as soon as possible while he continued northwards ‘in order to give aid and comfort to our very dear and faithful cousins the earl of Northumberland and his son at the battle honourably undertaken by them for us and our realm against our enemies the Scots’, after which he planned to proceed directly to Wales.

24

For two more days Henry continued north, reaching Nottingham on 12 July. It was here that he heard of Hotspur's revolt, and on the following day turned sharply west to Derby and then Burton-on-Trent, despatching messengers to the prince and writs to sheriffs, magnates and royal annuitants ordering them to come immediately to the king ‘to resist the malice of Henry Percy, who is referring to us merely as Henry of Lancaster and is issuing proclamations throughout Cheshire that King Richard is still alive’. The council was told to raise as much as it could in loans to pay the royalist troops, and a royal sumpterman was sent to spy on Hotspur's movements.

25

The 17 and 18 July were spent at Lichfield and the next night at St Thomas's priory near Stafford, probably to allow time for Henry's supporters to join him, but thoughts of further delay were dispelled by George Dunbar, who told the king that if he did not act swiftly Hotspur's army was only likely to grow.

26

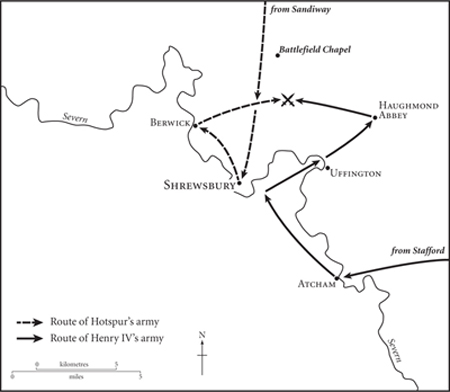

By 20 July both armies had arrived outside Shrewsbury.

Henry's rapid advance surprised Hotspur, who had been preparing to besiege Prince Henry in Shrewsbury but now retreated a few miles

north-west to the hamlet of Berwick.

27

The royal army, which had approached the town from the south-east, spent the evening crossing the Severn near Uffington before camping in the vicinity of Haughmond abbey. The early morning of Saturday 21 July saw both sides advance, Hotspur's eastward and the king's westward, then draw up within sight, but not bowshot, of each other two or three miles north of Shrewsbury. Several hours of talks followed, accounts of which vary.

28

The Dieulacres chronicler stated that Henry had written ‘amicable’ letters to Hotspur from Burton on 16 July offering to discuss his grievances, but had been rebuffed. Generally speaking, the chroniclers also credited Henry with taking the initiative to try to avoid bloodshed on the morning of the battle, although since they were in most respects sympathetic to the king's cause this is to be expected. One point on which they agreed was that Worcester took charge of the negotiations from Hotspur's side, and several of them blamed him for misrepresenting the king's emollient replies to Hotspur and thus scotching any chance of arbitration.

29

In reality, there was little chance of compromise, for Hotspur's fundamental grievance, on which all the sources concur, was his assertion that Henry had usurped the throne, a point Henry was never going to concede without a fight. Set against this simple unconquerable fact, the other accusations levelled against Henry – that he had raised excessive taxes, surrounded himself with evil counsellors, overridden the law, packed parliament, or failed to ransom Edmund Mortimer – were incidental to the negotiations on the morning of 21 July.

30

Map 5

The battle of Shrewsbury

Having come this far, Hotspur and Worcester had little option but to insist on Henry's removal: this was after all the basis on which they had recruited their army. What had brought them to this point was a good deal more complex, but tension between the king and Hotspur had been growing for at least two years. Wales was one source of contention, with Hotspur advocating a more conciliatory policy towards Glyn Dŵr (perhaps in order to free up men and money with which to defend the Scottish border), and the king accusing Hotspur of inappropriate, arguably treasonous, contact with the Welsh.

31

Another was Henry's failure to make adequate funds available to Hotspur and his father, either in Wales or, more importantly, on the Scottish marches, although given his financial problems the king actually seems to have tried quite hard to keep them

supplied.

32

Events during the autumn of 1402 had brought these tensions close to breaking-point, especially the king's refusal to allow the Percys to ransom Edmund Mortimer or to put the earl of Douglas to ransom, both of which Hotspur regarded as slights upon his family's honour. The favours shown by Henry to Westmorland and George Dunbar during 1402 also probably rankled. In sum, by the summer of 1403 Hotspur had come to believe that his expectations were unlikely to be fulfilled as long as Henry remained king and that only by gaining control of the crown and its resources could this be achieved. With his eleven-year-old nephew, the earl of March, on the throne, such control would have seemed assured.

Worcester must also have been tempted by this prospect. He had assumed such a range of responsibilities between 1399 and 1402, and was so well trusted by Henry, that he too may have come to believe that all that stood between the Percys and an unchallengeable ascendancy in the kingdom was the House of Lancaster.

33

On the other hand, he had lost the stewardship of the household in the spring of 1402 and the lieutenancy of Wales shortly afterwards, and perhaps sensed that the Percy star was on the wane. Like his nephew, he also questioned the king's policy in Wales.

34

Unlike his nephew, he was evidently capable of hiding his true feelings, and his decision to rebel was a shock to all, especially the king and the prince, not least because his enviable military reputation must have attracted recruits to the rebel army. Also in the rebel ranks was Hotspur's prisoner the earl of Douglas, for whom victory offered the prospect of turning the tables on his arch-enemy Dunbar, whereas defeat was unlikely to lead to disaster since he could not be accused of treason against the English king and was in any case too valuable a hostage.

35

Yet it was the battle-hardened Dunbar who proved the greater asset on the day, his influence on the outcome of the battle thought by some to have been pivotal. With the negotiations between the two sides dragging on into the afternoon

of 21 July, Dunbar warned the king that the rebels were only playing for time and advised him to attack.

36

Henry had come to the same conclusion: ‘as the day slipped away towards the hour of vespers’, wrote the Dieulacres chronicler, the king began to realize that what his enemies really wanted was to make Hotspur or his son king: ‘As long as I remain alive,’ exclaimed Henry, ‘I swear that that will never be. In the name of God, take the banners forward!’

37

The battle which followed was the first in which the massed formations of English and Welsh bowmen which had terrorized French and Scottish armies during the fourteenth century found themselves pitted against each other, and it would long be remembered as one of the bloodiest battles fought on English soil.

38

Henry deployed his army in three divisions, with the vanguard under the command of the twenty-five-year-old earl of Stafford (appointed constable in place of Northumberland a few hours before the battle) and the rearguard under the sixteen-year-old prince. The king kept Dunbar, who had fought many times both with and against Hotspur and Douglas, close by him in his own division. Hotspur's divisions were commanded by Douglas, Worcester and himself. He took up position on a gentle ridge overlooking farmland thick with peas, which he hoped would encumber any royalist advance, thereby nullifying the slight numerical advantage in the king's favour. Contemporaries referred to it as Hateley, Hussey, or Hinsey field.

39

The opening phase of the battle saw the two vanguards led by Stafford and Douglas advance towards each other before firing volley after volley of lethal arrows. Initially it seemed as if Hotspur's bowmen had secured the advantage, for the royalist vanguard, numbering some 4,000 men, broke and fled under the onslaught and the earl of Stafford was killed.

40

When the archers began to run short of ammunition,

Hotspur and Douglas, eager to press home their advantage, led a frontal assault on the division commanded by the king. It was a gamble born of desperation: Henry could not be allowed either to live or to escape. The fact that his standard-bearer, Sir Walter Blount, one of two knights wearing the royal arms as decoys, was killed, is an indication of how near Henry came to losing his own life; as the hand-to-hand fighting grew fiercer around him, he was persuaded by Dunbar to move to a safer position. Not so Prince Henry, who, despite being struck by an arrow which lodged in a bone just below his eye, refused to leave the field, instead leading the royalist rearguard in a counter-attack which broke through enemy lines before turning to encircle Hotspur's division. This was the decisive moment of the battle. At some point during the close-quarter fighting which ensued, Hotspur was killed, by whom is not known, and although some of his supporters set up a cry of ‘Henry Percy king!’, when they heard the king's answering shout of ‘Henry Percy is dead!’ their spirit broke and they began to flee. The pursuit was brutal but brief, for by this time darkness was encroaching. The eclipse of the moon which followed was providential, for the crescent moon was the Percy livery badge.

41

Casualties were heavy on both sides (unusually so for a victorious army), principally as a consequence of the murderous arrow-storm with which the engagement began. This was, said the Wigmore chronicler, a tragic and utterly lamentable battle (

bellum dolorissimum ac multum lamentabile

), in which ‘father killed son and son killed father, kin slew kin and neighbour slew neighbour’. Around 2,000 bodies, perhaps more, were buried in a mass grave on the site of the battle, others up to three miles distant; a further 3,000 or so were wounded, some of whom subsequently died. This probably represents about a quarter, perhaps a third, of the number who took part on both sides. Particularly shocking to contemporaries was the high proportion of men of gentle birth who perished at the hands of those undiscriminating reapers of late medieval English armies, the longbowmen.

42

Of the six divisional commanders, two were killed (Hotspur and

Stafford) and another two wounded (Prince Henry and the earl of Douglas, who was struck in the groin and lost a testicle before being captured by Sir James Harrington).

43

The account by the royal surgeon, John Bradmore, of the process by which he extracted the arrowhead buried in Prince Henry's face, which includes a drawing of the instrument which he designed to do so, provides graphic evidence of the potentially lethal nature of arrow-wounds.

44

Having removed the shaft, he wrote, ‘the head of the aforesaid arrow remained in the furthermost part of the bone of the skull for the depth of six inches’. To draw it out, Bradmore fashioned some probes from