Helmet for My Pillow: From Parris Island to the Pacific (36 page)

Read Helmet for My Pillow: From Parris Island to the Pacific Online

Authors: Robert Leckie

Tags: #General, #History, #United States, #World War II, #Military, #Autobiography, #Biography, #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Memoirs, #American, #Veterans, #Campaigns, #Military - United States, #Military - World War II, #Personal Narratives, #World War, #Pacific Area, #Robert, #1939-1945, #1920-, #Leckie

Russ Davis (“The Scholar”) on Pavuvu, 1944

Filthy Fred—the fourth new man—was a rawboned, eagle-beaked, easygoing farm lad from Kansas, full of the lore of the barnyard and with something of a rooster’s approach to life. He was fond of applying the standards of barnyard crises to those of human life, and was not only boring but disgusting—often provoking cries of outrage from these less-than-squeamish marines.

With these replacements, life on Pavuvu now turned to training designed to integrate the new men into the division. But many of the Old Salts disdained to go through that dull dispiriting routine again, and did as I did—secured a sinecure that kept them back in the battalion area. Others, like the Artist, simply stayed aloof.

Like Achilles, the Artist sulked in his tent. Many a morning at ten o’clock, after I had finished my duties with Lieutenant Liberal, the battalion censor, duties which consisted in licking envelope flaps and sealing them closed, I came to the Artist’s tent bringing a few slices of bread begged from the galley. The Artist would break out the little cans of caponata which his mother sent him regularly, and I would boil coffee and we would have a feast.

Coffee made the evenings, too. After the movies, the men would drop in to drink from the pot I had prepared. Warmed by this black liquid, they would talk and argue and jokingly discuss the comparative merits of my coffee-making and the rival beverage of the quartermaster sergeant. They would flatter me on my cooking—“best damn cuppa joe on Pavuvu”—but I think it was the conversation and not the coffee that drew them to my tent. My kitchen was not equal to the QM sergeant’s. He cooked his coffee over an acetylene torch, while I was reduced to boiling it in an old can over a tomato can filled with gasoline. But if he had the cuisine, my place had the atmosphere.

The books belonging to the Scholar and me—most especially, the almanac and the dictionary—made our tent a meeting place for the battalion literati. Then there was always an argument to be had with Eloquent, who was most obliging in opposing anyone. Then, too, there was the attraction of taking coffee from the hand of an “Asiatic.” This last is a term expressing the mixed reverence and fear for a man who has been in the tropics too long. I learned from Eloquent to embrace such a designation, for it made one an untouchable, almost, and automatically excluded one from dirty duty and the more prosaic forms such as falling out for calisthenics at reveille.

My having spent four weeks in the P-38 Ward on Banika made me the Asiatic par excellence. In my case, it was official. So none of the officers objected when I took to sealing the envelopes every morning for Lieutenant Liberal, avoiding all other duty, or when I clothed myself in a pair of moccasins and a khaki towel wrapped around my waist like a Melanesian’s lap lap. They shrugged and tapped their heads and called me Asiatic.

Now, a person thought to be different can exercise a peculiar attraction among men, and one result of my reputation was that every night, when I had finished writing letters on the rickety old typewriter I had bought for ten dollars, I could expect the tent to fill up with the men returning from the movie, eager for a cuppa joe and perhaps a full-scale argument between the two Asiatics—Eloquent and me.

Sometimes a bottle of whiskey would find its way to our tent, either purchased for some outrageous price, or, on one occasion, blackmailed from Lieutenant Liberal, when he, deciding that the men of the Intelligence Section should stand guard with the others, let fall the fatal remark, “I am an egalitarian myself,” and was immediately requested to extend his principles to his liquor ration. If the whiskey ran out too soon, I would coax a canteen of jungle juice from the Chuckler’s tent, or else we would drink our shaving lotion or hair tonic. Once I drank a horrible green concoction called Dupre, and awoke with a tongue that seemed to have been shaved and shampooed.

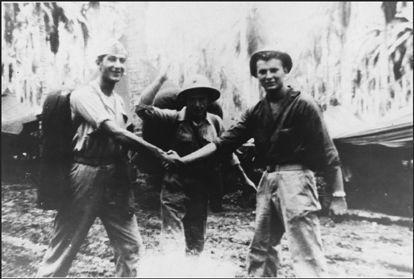

Milton Fogelman (“Eloquent”), Robert Leckie,

Russ Davis (“The Scholar”)

With alcohol rather than coffee, our voices rose from talk to song. Once again it was the ribaldries and the songs of World War One, and we even sank to a pitiful low when we began to hum classical symphonies in unison—a depth from which we were rescued by a macabre composition of our own inspired by the news that the division was ready to go again. To the tune of “Funiculi, Funicula” we sang a ghoulish serenade. We would form a circle around a man and sing:

Ya-mo, ya mo Playboy’s gonna die

Ya-mo, ya mo Playboy’s gonna die

He’s gonna die, he’s gonna die, he’s gonna DIE

So what the hell’s the use

You’re gonna die, you’re gonna die

.

We sang it to all, to everyone—except Liberal, the Artist and White-Man.

Word began to spread that the next one would be quick. It would not be like Guadalcanal or New Britain. It would be rough, real rough, while it lasted. But then, home for the Old Salts. We rejoiced. That was the best way—short and sweet.

Rutherford recovered his pistol. He came one night when all were at the movies and I was alone in the tent, typing a letter by the light of a piece of rope dipped in a can of gasoline. He and a friend came in out of the darkness, like conspirators. I was glad to be relieved of it, for I had been afraid someone would steal it from me.

“See you in the old home town,” Rutherford said, and slipped back into the dark with his comrade.

We left Pavuvu. Victors of Guadalcanal and New Britain, we went out to fight again; marching into the open-jawed landing craft driven up on the beach. Never before were we so confident of victory, never again would its price be so high.

3

Peleliu was already a holocaust.

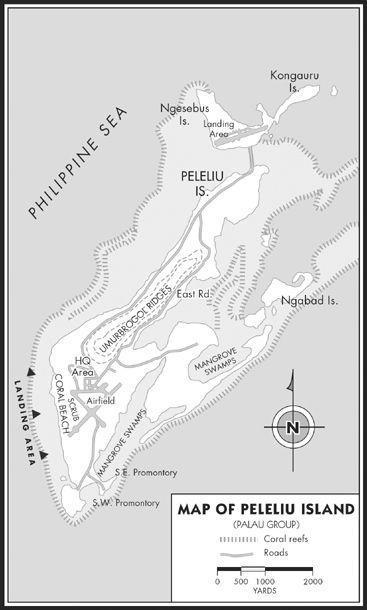

The island—flat and almost featureless—was an altar being prepared for the immolation of seventeen thousand men.

Army and Navy planes had pounded her. A vast naval armada of heavy cruisers and battleships had been lobbing their punishing missiles onto that coral fortress for days before our arrival. The little atoll—only five miles long, perhaps two wide at its broadest—was obscured beneath a pall of smoke. It was a cloud made pinkish by the light of the flames, and at times it would quiver and flicker like a neon sign, while the rumble of an especially heavy detonation came rolling out to us.

Our landing craft had disgorged our amtracks about a half mile from shore. We had come rolling out of their bowels like the ugly offspring of a monster Martian, and had felt the impact of a vast roaring and exploding and hissing and crackling—the sound of the bombardment, and, so it seemed to us, the sound of the utter destruction of that little island.

Our great warships lay behind us, and before us lay the foe. Overhead all of the airplanes were ours. It was a moment of supreme confidence. A fierce joy gripped me, banishing that silly conviction of death, and I ran my eye over all that bristling scene of conquest.

Naval shells hissed shoreward in the air above us. Those of us who had been on Guadalcanal, remembering our own ordeal with naval bombardment, could spare a pang of pity for the foe—thankful nevertheless for the new direction the war had taken. Slender rocket ships and destroyers were running close in to shore, as graceful as thoroughbred horses. When the rocket ships discharged their dread salvos there came a terrible roaring noise, like the introduction of hot steel into water, and the air above them would be darkened by flights of missiles.

Now, the great furor was dying down. The curtain of fire was lifting. In my exhilaration, I turned for a last look at our landing craft, and saw the prow black with sailors waving us on, shaking clenched fists in the direction of Peleliu as though they were spectators come to see the gladiators perform.

Now, at once, silence.

The motors of our tractors roared, and we churned toward that cloud of smoke.

I had my head above the gunwales because I had chosen to man the machine gun. So had the Hoosier in a nearby amtrack. He caught sight of me, nodded toward the island and grinned. I read his meaning and lifted my hand in the gesture of perfection.

“Duck soup,” I shouted into the wind and noise.

Hoosier grinned again and returned the salute, and at that moment, there came an odd bump against the steel side of our craft and then a strangled sound. The water began to erupt in little geysers and the air became populated with exploding steel.

The enemy was saluting us. They were receiving us with mortar and artillery fire. Ten thousand Japanese awaited us on the island of Peleliu, ten thousand men as brave and determined and skillful as ever a garrison was since the art of warfare began. Skillful, yes: it was a terrible rain and it did terrible work among us before we reached the beach.

At that first detonation, Hoosier and I had ducked below the gunwales, and I had not dared raise my head again until we were a hundred feet offshore.

Our amtrack was among the first assault waves, yet the beach was already a litter of burning, blackened amphibian tractors, of dead and wounded, a mortal garden of exploding mortar shells. Holes had been scooped in the white sand or had been blasted out by the shells, the beach was pocked with holes—all filled with green-clad helmeted marines.

We were pinned down.

Russ Davis and Bill Smith (“Hoosier”)

With Lieutenant Deepchest of F Company, to whom Filthy Fred and the mild Twin and I had been assigned, I leapt over the side of our amtrack and scraped a hole of my own. Behind me a shell landed, blowing a man clear out of his high-laced jungle boots. He was the fellow who had been with me on New Britain when the Japs had come up behind me, the one who had fired over my head. He lived, but the war was over for him.

Lieutenant Deepchest tried to say something but I could not hear, motioning to him to write it down. He shrugged: it was not important. Just then, a marine came dashing over a sand dune in front of me, his face contorted with fear, one hand clutching the other, on which the tip of the index finger had been shot away—the stump spouting carmine like a roman candle. It was the corporal who had earned Chuckler’s enmity the night of the Tenaru fight on Guadalcanal, when our machine gun, which he had set up, had slumped into the mud. Now, behind that fearful face, I thought I detected amazement and relief.