Hell (24 page)

When I leave my

cell, plastic tray and plastic plate in hand, I join a queue of six prisoners

at the hotplate. The next six inmates are not allowed to join the queue until

the previous six have been served. This is to avoid a long queue and fighting

breaking out over the food. At the right-hand end of the hotplate sits Paul

(murder) who checks your name and announces

Fossett

,

C., Pugh, B.,

Clarke, B., etc.

When he ticks my name off, the six men

behind the counter, who are all dressed in long white coats, white headgear and

wear thin rubber gloves for handling the potatoes or bread, go into a huddle

because they know by now there’s a fifty-fifty chance I won’t want anything and

will return to my cell empty-handed.

Tony (marijuana

only, escaped to Paris) has recently got into the habit of selecting my meal

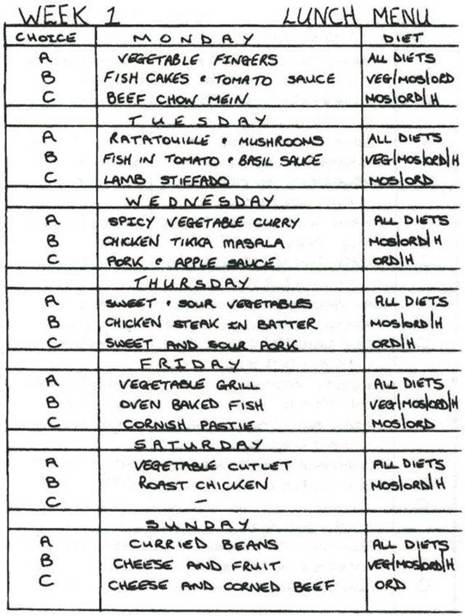

for me. Today he suggests the steak and kidney pie, slightly underdone, the

cauliflower au gratin with duchesse potatoes, or, ‘My Lord, you could settle for

the creamy vegetable pie.’ The server’s

humour

has

reached the stage of cutting one potato in quarters and placing a diced carrot

on top and then depositing it in the

centre

of my

plastic plate. Mind you, if there’s chocolate ice-cream or a lollipop, Del Boy

always makes sure I end up with two. I never ate puddings before I went to

prison.

But today, Tony

tells me, there’s a special on the menu: shepherd’s pie. Now I am a world

expert on shepherd’s pie, as it has, for the past twenty years, been the main

dish at my Christmas party. I’ve eaten shepherd’s pie at the Ivy, the Savoy and

even Club 21 in New York, but I have never seen anything like

Belmarsh’s

version of that particular dish. The meat, if it

is meat, is glued to the potato, and then deposited on your plastic plate in

one large blob, resembling a Turner Prize entry. If submitted, I feel confident

it would be shortlisted.

Tony adds, ‘I

do apologize, my Lord, but we’re out of Krug. However,

Belmarsh

has a rare vintage tap water 2001, with added bromide.’ I settle for creamy

vegetable pie, an unripe apple and a glass of Highland Spring (49p).

An officer

comes to pick me up and escort me to the Deputy Governor’s office. Once again,

I feel like an errant schoolboy who is off to visit the headmaster. Once again

the headmaster is half my age.

Mr

Leader introduces himself and tells me he has some good

news and some bad news.

He begins by

explaining that, because Emma Nicholson wrote to Scotland Yard demanding an

inquiry into the collecting and distribution of funds

raised

for the Kurds, I will have to remain a C-cat prisoner, and will not be

reinstated as a D-cat until the police have completed their investigation. On

the word of one vengeful woman, I have to suffer further injustice.

The good news,

he tells me, is that I will not be going to

Camphill

on the Isle of Wight, but will be sent to Elmer in Kent, and as soon as my

D-cat has been reinstated, I will move on to Springhill. I complain bitterly

about the first decision, but quickly come to realize that

Mr

Leader isn’t going to budge. He even accuses me of ‘having an attitude’ when I

attempt to enter a debate on the subject. He wouldn’t last very long in the

House of Commons.

‘It wasn’t my

fault,’ he claims. ‘It was the police’s decision to instigate an inquiry.’

Association.

David (life imprisonment, possession of a gun)

is the only person watching the cricket on television. I pull up a chair and

join him. It’s raining, so they’re showing the highlights of the first two

innings. I almost forget my worries, despite the fact that if I was ‘on the

out’, I wouldn’t be watching the replay, I would be at the ground, sitting

under an umbrella.

I skip supper

and continue writing, which causes a riot, or near riot. I didn’t realize that

Paul has to tick off every name from the four spurs, and if the ticks don’t

tally with the number of prisoners, the authorities assume someone has escaped.

The truth is that I’ve only tried to escape supper.

Mr

Weedon

arrives outside my

cell. I look up from my desk and put down my pen.

‘You haven’t

had any supper, Archer,’ he says.

‘No, I just

couldn’t face it.’

‘That’s a

reportable offence.’

‘What, not

eating?’ I ask in disbelief.

‘Yes, the

Governor will want to know if you’re on hunger strike.’

‘I never

thought of that,’ I said. ‘Will it get me out of here?’

‘No, it will

get you back on the hospital wing.’

‘Anything but that.

What do I have to do?’

‘Eat

something.’

I pick up my

plastic plate and go downstairs. Paul and the whole hotplate team are waiting,

and greet me with a round of applause with added cries of, ‘Good evening, my

Lord, your usual table.’ I select one boiled potato, have my name ticked off,

and return to my cell. The system feels safe again. The rebel has conformed.

I have a visit

from Tony (marijuana only, escaped to France) and he asks if I’d like to join

him in his cell on the second floor, as if he were inviting a colleague to pop

into his office for a chat about the latest sales figures.

When you enter

a prisoner’s cell, you immediately gain an impression of the type of person

they are. Fletch has books and pamphlets strewn all over the place that will

assist new prisoners to get through their first few days. Del Boy has tobacco,

phonecards

and food, and only he knows what else under the

bed, as he’s the spur’s ‘insider dealer’.

Billy’s shelves

are packed with academic books and files relating to his degree course.

Paul has a wall

covered in nude pictures, mostly Chinese, and Michael only has photos of his

family, mainly of his wife and

sixmonth

-old child.

Tony is a

mature man, fifty-four, and his shelves are littered with books on quantum

mechanics, a lifelong hobby. On his bed is a copy of today’s

Times

, which, when he has read it, will

be passed on to Billy; reading a paper a day late when you have an

eighteenyear

sentence is somehow not that important. In a

corner of the room is a large stack of old copies of the

Financial Times

. I already have a feeling Tony’s story is going to

be a little different.

He tells me

that he comes from a middleclass family, had a good upbringing, and a happy

childhood. His father was a senior manager with a top life-assurance fund, and

his mother a housewife. He attended the local grammar school, where he obtained

twelve O-levels, four

A-

levels and an S-level, and was

offered a place at London University, but his father wanted him to be an

actuary.

Within a year

of qualifying he knew that wasn’t how he wanted to spend his life, and decided

to open a butcher’s shop with an old school friend. He married his friend’s

sister, and they have two children (a daughter who recently took a first-class

honours

degree at Bristol, and a son who is sixteen and, as

I write, boarding at a well-known public school).

By the age of

thirty, Tony had become fed up with the hours a butcher has to endure; at the

slaughterhouse by three every morning, and then not closing the shop until six

at night. He sold out at the age of thirty-five and, having more than enough

money, decided to retire. Within weeks he was bored, so he invested in a Jaguar

dealership, and proceeded to make a second fortune during the Thatcher years.

Once again, he sold out, once again determined to retire, because he was seeing

so little of his family, and his wife was threatening to leave him. But it

wasn’t too long before he needed to find something to occupy his time, so he

bought a rundown pub in the East End. Tony thought this would be a distracting

hobby until he ended up with fourteen pubs, and a wife whom he hardly saw.

He sold out once

more. Having parted from his wife, he found himself a new partner, a woman of

thirty-seven who ran her own family business. Tony was forty-five at the time.

He moved in with her and quickly discovered that the family business was drugs.

The family concentrated on marijuana and wouldn’t touch anything hard. There’s

more than a large enough market out there not to bother with hard drugs, he

assures me. Tony made it clear from the start that he had no interest in drugs,

and was wealthy enough not to have anything to do with the family business.

The problem of

living with this lady, he explained, was that he quickly discovered how

incompetently the family firm was being run, so he began to pass on to his

partner some simple business maxims. As the months went by he found that he was

becoming more and more embroiled, until he ended up as titular MD. The

following year they tripled their profits.

‘Meat, cars,

pubs, Jeffrey,’ he said, ‘marijuana is no different. For me it was just another

business that needed to be run properly. I shouldn’t have become involved,’ he

admits, ‘but I was bored, and annoyed by how incompetent her and her family

were and to be fair, she was good in bed.’

Now here is the

real rub. Tony was sentenced to twelve years for a crime he didn’t commit. But

he does admit quite openly that they could have nailed him for a similar crime

several times over. He was apparently visiting a house he owned to collect the

rent from a tenant who had failed to pay a penny for the past six months when

the police burst in. They found a fifty-kilo package of marijuana hidden in a

cupboard under the stairs, and charged him with being a supplier. He actually

knew nothing about that particular stash, and was innocent of the charges laid

against him, but guilty of several other similar offences. So he doesn’t

complain, and accepts his punishment.

Very British.

After Tony had

served three and a half years, they moved him to Ford Open, a D-cat prison,

from where he visited Paris, as already recorded in this diary. He then moved

on to

Mijas

in Spain, and found a job as an engineer,

but a friend shafted him – a sort of Ted Francis, he says – ‘so I was arrested

and spent sixteen months in a Spanish jail, while my extradition papers were

being sorted out. They finally sent me back to

Belmarsh

,

where I will remain until I’ve completed my sentence.’ He reminds me that no

one has ever escaped from

Belmarsh

.

‘But what

happened to the girl?’ I ask.

‘She got the

house, all my money and has never been charged with any offence.’ He smiles,

and doesn’t appear to be bitter about it. ‘I can always make money again,’ he

says.

‘That won’t be

a problem, and I feel sure there will be other women.’