Heirs to Forgotten Kingdoms (6 page)

Religions that instructed their followers to punish or subordinate the body so that the mind could be made free are often called “Gnostic,” and there were several such at this time. Patik discovered that a number of austere communities had recently been established in the Iraqi Marshes. The Mandaeans were one of these, but their rules perhaps were not strict enough for Patik. (Although the Mandaeans may have been vegetarian at some point in their history, they never favored celibacy.) A nearby community fitted better with the instructions that the voice had given him. Not only did they never eat meat, have sex, or drink alcohol, but they also avoided art and music. Otherwise they tried to strictly follow both Jewish law and the Christian gospels. Each family seems to have had a plot of land where they grew vegetables and fruit to eat. Later writers called them the Mughtasila, which in Arabic means “the washers,” because of their practice of baptism in the rivers of the marshes. It was the Mughtasila that Patik and his already pregnant wife joined, and shortly afterward their only child was born. They named him Mani.

As Mani grew up, he went through a period of rebellion. It did not involve sex or alcohol. Instead, he chafed at the restrictions on art. He was a talented artist and longed to express his ideas visually as well as with musical hymns. The Mandaeans, living nearby in the marshes, were an inspiration: although they rejected Jesus, whom Mani admired, he appreciated their music and borrowed one of their hymns. In other ways, however, he found his own community’s rules too lax. Giving up meat was not enough, he said. To kill and eat vegetables was cruel to plants, and he could even hear the fig tree weep for the fruit that was cut from its branches. The springs of fresh water complained, he said, when the Mughtasila bathed in them, because they were polluting the water. (His own followers in later years apparently would wash themselves using their own urine instead.) Eventually Mani claimed to have received a new revelation—an account of a cosmic battle between light and darkness.

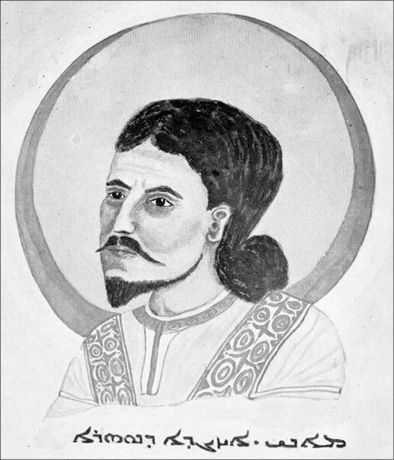

A modern representation of Mani, a third-century founder of a religion that competed with early Christianity and whose division of the universe between good and evil gave rise to the term “Manichean.” He was preceded and influenced by the Mandaeans.

According to St. Augustine, who followed Mani’s teachings for a time before becoming a Christian, Mani taught that the universe contained “two antagonistic masses, both of which were infinite”—one good, the other evil. “Evil was some . . . kind of substance, a shapeless, hideous mass . . . a kind of evil mind filtering through the substance they called earth.” Evil was the source of all darkness in the universe, including eclipses of the sun and moon and the alternation of day and night. To Mani, day following night, and night following day, were signs of a constant battle between light and darkness. To this day, we speak of a “Manichean worldview” to mean one that divides the world into the forces of good and the forces of evil. (

Mani chai

was what Mani’s followers cried in Aramaic: it means “Mani is alive.” So his followers came to be called Manichees or Manicheans.)

For religiously enlightened Manichees, the highest calling was to free the spirit from the bonds of matter. For the truly committed—the “elders,” as they were called (the same word,

sheikh

in Arabic, is applied to Mandaean priests)—this meant never having children, eating only fruit, and atoning for plucking that fruit. Wasting water was a sin. Killing animals was unthinkable. Strict Manichees would not kill a fly. “Let [the country] . . . with smoking blood change into one where the people eat vegetables,” as a Manichee prayer declared. The religion also offered a chance of salvation, however, to people who wanted to follow Mani without observing all his rules: after all, someone had to commit the sin of plucking the fruit for the elders to eat. The elders absolved their followers of this sin by digesting their food according to a strict ritual, which was meant to liberate the fragments of light trapped inside the food. This structure of elders and followers meant that the religion had people of exemplary austerity who were capable of interceding with God on behalf of the whole community, leaving their followers free to live as they chose, provided that they maintained and respected the elders. As we will see, this structure is still used by some Middle Eastern faiths today.

In around the year 240 Mani left the marshes and the community where he had been brought up and traveled east to the capital of the Parthian Empire. He was a distinctive figure in his multicolored coat, striped trousers, and high boots. Helped by his family’s aristocratic connections and the general laissez-faire attitude of the Parthians toward religion, he almost succeeded in converting the emperor to his cause—and was executed for his efforts. But his religion continued to spread. As his followers went east from Iran, they relied on Buddhist iconography to explain their message. Mani was presented as “the Buddha of Light.” A Manichee kingdom was established among the central Asian Uyghurs. In later centuries, Manichees became numerous in China, where they were best known for their refusal to eat meat. “Vegetarian demon worshipers” was the way the authorities described them in an edict in 1141. Official persecution winnowed their numbers, but they may have survived in southern China until the turn of the twentieth century. Indeed, it appears that Mani is still worshiped in one place in China today, though accidentally: at a temple in eastern China, a statue of a Buddha with a beard and straight hair dates back to the time when the temple was built by Manichees—and was probably originally a statue of Mani.

In the West, Manicheism taught reverence for Jesus and was a serious competitor to early Christianity. A Manichee called Sebastianus almost became the emperor of Rome in the middle of the fourth century: if he had, world history would have been very different. Instead, Manicheism largely disappeared in the lands of the empire, as Christianity became the state religion of Rome and Roman authorities began to stamp out rival faiths. It survived longer among the Muslims, and Manichees even worked in the center of government—until the eighth-century caliph al-Mahdi decided that its adherents had become too powerful, and crucified large numbers of them. The Muslim scholar Ibn al-Nadim, who left the account of Mani’s life on which the above is based, knew a few Manichees in Baghdad in the tenth century, but they do not seem to have survived much longer than that under Islamic rule.

Manicheism nevertheless left a lasting mark on European civilization. There is some evidence that Christians felt the need to imitate the unsurpassed austerity of Mani’s holy men and women. Inspired by their belief that matter was permeated with evil and was a prison for the soul, the Manichee elect tried to thwart all bodily impulses—and Christian hermits followed suit, denying themselves sleep, eating only grass and fruit, and sometimes castrating themselves. Christian monasticism was particularly strong in Egypt, where Manichee monasteries had already been established. St. Augustine, a strong believer in original sin and an advocate of chastity, had been a Manichee and felt the need to combat its appeal. In short, modern Christian asceticism and monasticism may still owe a debt to Mani.

The Mandaeans are neither Manichees nor Mughtasila. Unlike both of those groups, they reject Jesus and believe that marrying and having children are moral obligations. But in other ways they have many things in common with the Manichees. They reject Abraham and believe that the body is a prison for the soul. They believe in an angel of light, Hibil Ziwa, who is always contending with darkness. Mandaeans believe themselves to be sparks of the cosmic light that have detached themselves from it and become trapped in a material home. When liberated by death from their bodily prisons, these sparks of light can ascend back to the great light from which they once came. So at a funeral, a Mandaean priest may address the soul of a dead man as follows: “You have left corruption behind and the stinking body in which you found yourself, the abode of the wicked, the place which is all sin, the World of Darkness, of hatred, envy, and strife, the abode in which the planets live, bringing sorrows and infirmities.” And the Mandaeans believe that the manner in which a priest eats a sacred meal at the funeral of a deceased member of the faith can make a difference to that person’s fate in the afterlife. All of these are ideas and practices that would have been familiar to the followers of that other Iraqi religion, Manicheism. The Mandaeans therefore are a link not only to the ancient history of the Middle East but to the history of Christianity as well.

—————

THE MANDAEANS PROBABLY NUMBER

fewer than a hundred thousand in the whole world, and until 2003 most of them lived in Iraq. Not all of them are religious, as I discovered when I had my second encounter with a Mandaean—this time in a café in Manhattan, in 2009. Nadia Gattan was visiting the United States from Britain, which had given her asylum. Though she had left Iraq, she remained, as she put it, “hard-core Iraqi. We’re matter-of-fact people, not interested in glamour. I’m emotional, passionate, not like Europeans.” Brought up in a left-wing family in the Baghdad suburbs, Nadia saw herself as Iraqi first and Mandaean second. Her friends came from many different religions, and her parents were not especially observant. “I was taught nothing about religion,” she went on, “only moral rules: not to lie, not to steal, always to remember that I was a woman.”

The Mandaean holy books were not available for Nadia to read, as they were kept by priests in a chapel called the

mandi

. Her family did not pray, and in their home in Baghdad, which she described to me, it would have taken a sharp eye to spot anything that marked them as different from other middle-class, secular Iraqi families. It was an absence, not a presence, that would meet the eye at first. The walls were not decorated with the sacred writing of the Koran, nor any photograph of the great Ka’aba of Mecca with thousands of white-clad pilgrims circling it, nor (as the Shi’a Muslims tend to have) a portrait of Imam Hussein. On a closer look, a privileged visitor might have seen more evidence of Mandaeanism. A discreet picture of the

darfesh

hung on the wall of the living room. The family’s white baptismal robes and girdles, used for sacred immersions in the water of the Tigris River, were stored in a cupboard kept free from all impurity, ready for the rare occasions when they would be needed.

Nadia was brought up in Baghdad, but her family had only moved there in the 1970s. Before then they had lived in a small town in the south of Iraq called Suq ash-Shuyukh (literally, “the elders’ market”). Nadia’s father had been a teacher there, with a small gold shop as a side business. And it was when the family went back there for Mandaean festivals that Nadia really experienced her religion properly, spending time with her devout grandparents. In an old photo that Nadia showed me, I saw her grandfather: surrounded by children dressed in Western-style clothes, he was an old man with a long beard and a red-and-white

keffiyeh.

He ate meat only if it had been taken from an unblemished male animal that had been slaughtered while facing north and then bled dry, and only his wife was allowed to prepare it. She was next to him in the photograph: an equally devout woman, dressed all in black and wearing a veil over her hair. He was a blacksmith and she practiced traditional medicine, treating the eye diseases that local farmers would get during the rice harvest. When she visited these grandparents, Nadia was told that if she was menstruating, she had to sit at a separate table. This was the strict enforcement of a rule shared by both ancient Babylonians and Jews (in Babylon a man who touched a menstruating woman was impure for six days). With Nadia it came to an end. She refused, and eventually her grandparents stopped complaining that she was violating the rules.

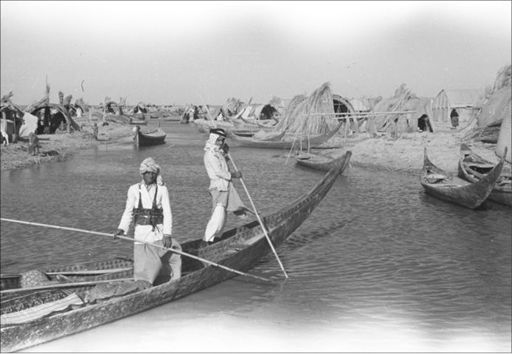

This couple had arrived in Suq ash-Shuyukh in 1949. Before that they had lived out in the Iraqi Marshes, the vast maze of small islands, reedbeds, and shallow rivulets that bordered the town on its eastern side. The majority of the population consisted of fiercely independent Muslim tribes. The British traveler Wilfrid Thesiger lived there in the 1950s and described it as a “world complete in itself,” with minimal interference from the outside. He was fascinated by the tribes, among whom he found a curious mix of tolerance (accepting tomboy women who slept with other women, for example) and rigidity (the laws governing cleanliness were so strict that a man might see his son bleed to death and not touch him for fear of making himself ritually unclean).