Heidegger's Glasses: A Novel (33 page)

Read Heidegger's Glasses: A Novel Online

Authors: Thaisa Frank

She asked Lodenstein to tie the red ribbon around her wrist.

Marianne,You wouldn’t think anything could grow in a place like this—but there’s grass where the red snow used to be.Love,Patrice

It was the time of feverfew. Before Elie went to the outpost, she picked a large bouquet from the forest. The feverfew grew in clusters, far apart, and Elie took her time. Without the weight of snow, the pines seemed buoyant, free of burdens. The first winter after the winter of Stalingrad had passed, and it seemed as though the world had come a full cycle. Elie sat beneath a pine—hidden, protected, smelling the bare earth. She remembered playing house with her sister under trees. The wooden sticks were dolls. The boughs were their dresses. Her sister Gabriela named her dolls after friends she had at school, and Elie named hers after characters she loved in fairy tales. One spring, they found a wild rabbit. They fed it carrots. It kept them company under the trees.

By the time Elie emerged, it was late afternoon. She brought the feverfew to her jeep and drove through the slanted light, still looking for people in the woods. Yet she felt a giddy sense of release and didn’t care that she hadn’t heard from Goebbels in months.

The houses in this village in Northern Germany were still clean, orderly, not yet bombed. Elie drove to the outpost and walked across the field, milkweed brushing against her shoes. She knocked twice, no one answered, and she let herself in. The place was more of a jumble shop than ever. Chairs on top of chairs, a sofa filled with filing cabinets. The officer was shoving clothes into a suitcase.

What are you doing here? he said. You must know there isn’t any mail.

Lodenstein sent me, said Elie, handing him half the flowers. People need to amuse themselves.

The officer threw the flowers on an ottoman.

What could be amusing here?

Elie pointed to more playing cards. Then she pointed to some rusty metal instruments, polishing stones, and an eye chart. She’d wanted to find a box of cast molten glass from the lens manufacturer Saegmuller and Zeiss. But she only found glass from a manufacturer she didn’t recognize. One of the optometrist’s chairs was still against the wall. She pointed to it.

How can optometry equipment be amusing? said the officer.

Stumpf broke his glasses.

That bumpkin, said the officer. He throttled sheets from the bed he once tried to get Elie to sleep in. A revolver fell to the floor, and he crammed it in his suitcase.

Has Stumpf been bothering you? said Elie.

No, said the officer. And I wouldn’t give a damn if he was. I don’t care about Goebbels either.

Elie smiled. Then your neck is safe.

I don’t care about my neck. The whole thing’s going to hell. Look at Ardennes, and the damn Allies past the Rhine. No one’s safe, and I’m getting out of here. Take whatever the fuck you want.

Elie watched while he dragged a duffel bag to his Kübelwagen and found herself alone in the outpost. The blackout curtains flapped. A few beams from the roof were on the ground. And the floor was littered with papers. Elie looked through all of them. Each detailed shipments of confiscated goods except for a note that read:

NO MORE FUCKING PIECES OF FURNITURE. SOMEONE IS BOUND TO FIND THEM.

NO MORE FUCKING PIECES OF FURNITURE. SOMEONE IS BOUND TO FIND THEM.

Elie pulled out everything from the wall: the polishing stones, the metal, the eye chart, the box of molten glass, and the playing cards. She took rations of flour, dried milk, sausage, knäckebrot, cheese—whatever food she could find. The food was in heavy cumbersome boxes, and she had to carry them one at a time across the milkweed-covered field. Last was the optometry chair, which she lugged in fits and starts. She set it down and paused to look at the sky.

It was almost night—too early to see anything but the evening star, a soft beacon in the sky. She shoved the chair into her jeep and drove off in the spring evening. A half moon lit green rhododendrons by the side of the road, and Elie’s fear of the dark disappeared—as though every mote of dark evaporated in the moonlight. She looked in the rearview mirror and saw that no one was following her.

Enough

, she thought.

, she thought.

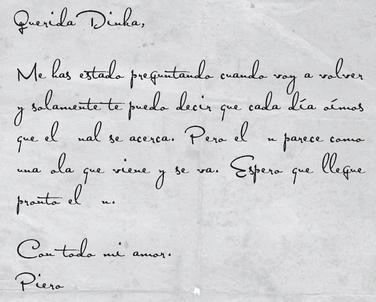

Dear Dinka,You have asked when I may be back and I can only tell you that every day we hear the end is coming. Yet it recedes, a frontier that’s always breathing in and out. May it come soon.Love,Piero

Asher had wondered, with some irony, whether he’d be getting back his own optometry chair from Freiburg. But this chair was light brown, and there were three bullet holes in the back. To make sure the chart was illuminated, he made Stumpf create a tent from black merino cloth Elie brought from the outpost almost a year ago. It was a haphazard structure with a large opening, and that made Stumpf even more of a public spectacle. Scribes watched while he held a patch over one eye and whined

Besser

and

Nicht Besser

for different lenses. Since Elie hadn’t been able to find the best materials, Asher struggled to make them work. He polished rusty instruments, ground cheap glass until the lenses were right, and made the earpieces twice because Stumpf’s chins rose around his face like a ruff. When he finally produced the glasses, Stumpf said he could see better with these glasses than any he’d ever had. The Scribes wanted glasses too, whether they needed them or not.

Besser

and

Nicht Besser

for different lenses. Since Elie hadn’t been able to find the best materials, Asher struggled to make them work. He polished rusty instruments, ground cheap glass until the lenses were right, and made the earpieces twice because Stumpf’s chins rose around his face like a ruff. When he finally produced the glasses, Stumpf said he could see better with these glasses than any he’d ever had. The Scribes wanted glasses too, whether they needed them or not.

Asher made glasses whenever he felt like it. No one could object, least of all Stumpf, who was abjectly grateful because it meant he could drive to his brother’s farm—a visit he kept postponing since now he was drawn to a psychic named Hermione Rosebury, who said she’d known Madame Blavatsky. Hermione was the only Scribe in the Compound from England, although she spoke perfect German. Her sense of isolation made her willing to ignore the fact that Stumpf slunk around the Compound obsequiously, forsaken by Sonia Markova who had taken up with Parvis Nafissian. He had long since been deprived of any authority, including the right to make people imagine Goebbels. Also, with no more letters coming to the Compound, he’d given up insisting the Scribes answer them. He stored them in his office and answered them himself, or—more often—thought about answering them, since he only understood the German.

In the midst of the craze about glasses, Lars Eisenscher paced the small round room of the shepherd’s hut. He hadn’t received a letter from his father for almost three months and didn’t know whether his father was back in jail, had gone to another country, been shot, or didn’t want to cause trouble by writing him. Twice Lars had gone to the post office in town and was told the postal system barely functioned. Germany was exhausted, and the war had taken all of her resources, even the simple ability to send a letter. Paper, ink, people one loved—all were forsaken by the war.

Lars, who was lost in worry, looked up when he heard a Kübelwagen rumble into the clearing. It drove quickly, flattening flowers, making deep cuts in patches of new grass. A short, dark officer got out and asked for Obërst Lodenstein. If Lodenstein hadn’t spent time with Goebbels in his odious office, he might have thought the officer was Goebbels himself, paying his mythical visit. Lodenstein kept the officer at the door while Lars stood at a distance. He was weighted with medals—more than Mueller, almost as many as Goebbels. Lars looked at him warily. So many medals signaled power.

That guard of yours needs a haircut, said the officer.

He’s on duty more than seventeen hours a day, said Lodenstein.

I can’t quibble about hours, said the officer. I can only point out standards.

He reached into his pocket and handed him a memo from the Ministry of Enlightenment and Propaganda. The paper was thick, strong, unblemished. It read:

The Office requests a roll call of all Scribes

.

The Office requests a roll call of all Scribes

.

Lodenstein acted as though the letter wasn’t worthy of attention. What do you make of this? he said.

There’s nothing to make of it, said the officer. Just get everybody up here with their papers.

But they’re imagining Goebbels.

The officer looked confused, and Lodenstein said:

Hasn’t anyone ever told you about this important ritual?

The officer shook his head, and Lodenstein, whose heart was thumping, explained that every day the Scribes spent half an hour invoking an image of Joseph Goebbels—the mind behind this vital project.

If they didn’t remember him, he said, nothing would get done. Interruption could mean catastrophe.

Other books

Inspector Morse 4 - Service Of All The Dead by Colin Dexter

Love's Someday by Robin Alexander

Dive Right In by Matt Christopher

Reunited with the Cowboy by Carolyne Aarsen

Entrevista con el vampiro by Anne Rice

Tiana (Starkis Family #3) by Cheryl Douglas

Nantucket Red (Nantucket Blue) by Leila Howland

Home by Brenda Kearns

The Rendering by Joel Naftali

Never a Bride by Grey, Amelia