Hef's Little Black Book (4 page)

Read Hef's Little Black Book Online

Authors: Hugh M. Hefner

I

f It Goes Away, It Will Come Again

The best antidote for a lost love is a new one.

We delude ourselves with the notion that somehow there is only one person out there who is a soulmate waiting for you. Emotionally, you don’t fully believe that you can ever have those feelings again for someone new, that you’ll ever find another comparable. That’s an illusion. You can find it again because what you’re really finding, by and large, is someone with common interests onto whom you can project your own needs and desires.

The reality is that life, especially in this regard, is like a movie: There are many appropriate people who can be cast in that costarring role. When you’re dealing with lost love, it’s time to just start the casting process all over again.

O

nly Fools Don’t Fall Once More

Broken hearts are like broken legs. They needn’t be fatal. Only a foolish person doesn’t leave the heart open for the joy and pain of love again. If not, you are the loser for it. In fact, you are half alive if you are not either in love or willing to continue to have the capacity for those feelings.

T

ime Itself Tells the Truth

I see relationships at the time through a romantic haze. Only later on do you get some sense of what the relationship was really all about.

“We’ve all been there,” he has said of love gone awry. “We’ve all had our punches in the gut.” His favorite film is

Casablanca

, and he often sees himself as Rick Blaine waiting at the Paris train depot for Ilsa Lund, who never comes, reading her farewell letter in the rain, which blurs the ink. He often views himself as the guy left standing in the rain, if only temporarily. One of his secretaries once noted: “He imagined at every party that he would see a girl across a crowded room, their eyes would meet, violins would start to play, and he would feel that pit-a-pat.” So it was that three days after Barbi had moved out for good, he threw himself a party stocked as ever with dozens of beautiful women. And there his eyes met those of a cherubic nineteen-year-old former Bible-school teacher named Sondra Theodore. Violins did not play, but Barry White’s “Baby Blue Panties” did, and they danced to it as their first dance and made love that very night. She would soon be wearing a diamond necklace that spelled out the words

Baby Blue

and would be known for the next five years as his Special Lady. Moss, it turns out, grows only outside the Playboy Mansion.

A

nd so one man created two houses and all men would forever want to go to these houses, to be inside. It began with a house in Chicago, where he too began: “I remember, in the days prior to the magazine, walking the streets of Chicago late at night, looking at the lights in the high-rise apartment buildings and very much wanting to be part of the good life I thought the people in those buildings must be leading.” And so he wanted. And so he got. Eventually, that which was once considered urban good life would, in this particular Chicago house, under this particular man’s sway, turn into Good Life supernova. This house, his house, of course, was the original Playboy Mansion, a stately turn-of-the-century monolith, a mere seventy rooms looming, glistening, three blocks from Lake Michigan, imposing its majesty on a leafy Gold Coast street of swells all forever to be outswelled. Six years into his empire-building, in a 1959 year-end letter to stockholders, the manor’s prescient future occupant—this thirty-three-year-old workaholic editor/ publisher/dreamer—wrote, almost as an afterthought: “On the personal side, we’ve bought a house at 1340 North State Parkway, which should make the living considerably easier and more pleasant. It is a magnificent place, with a

giant main room that will be great for parties; we’re building an elaborate indoor swimming pool downstairs that will make this mansion the talk of all Chicago. It should help me get away from the office scene a bit and relax a little more.”

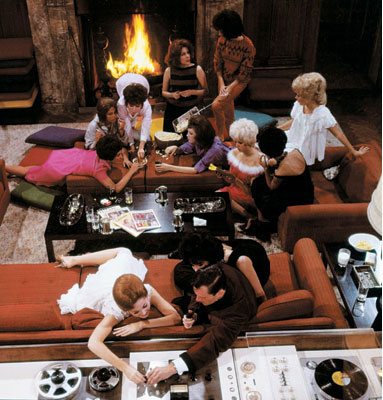

Once he sealed himself within his grand new vacuum, work and play fused, intermingled, moved as one. Regimen knew no boundaries—a beautiful thing. Why commute? Just move the paperwork off the bed and make room for the girls. Hours were not wasted as much as savored. “Separates me from the wasted motions,” he said. Also, most memorably: “The Mansion ended up working so well that going out came to seem like a useless exercise. What the hell was I supposed to go out for?” He barely went out, for certain. Maybe eight times in nine years, or so myth has it, but no one kept score, really. Once, when he and a Lady stepped outdoors during a blizzard to build a snowman in the front yard,

panic seized the staff—“like there’d been a prison break,” he would say, chuckling. “He’s

gone out!

Hef’s gone out!’”

He was never lonely therein. On a white French door that gave way to his vast ballroom—where two suits of armor stood sentry over bacchanals unending—there was affixed the most notorious brass plaque in the history of threshold passage. In Latin, it warned:

Si Non Oscillas Noli Tintinnare.

(“If you don’t swing, don’t ring.”)

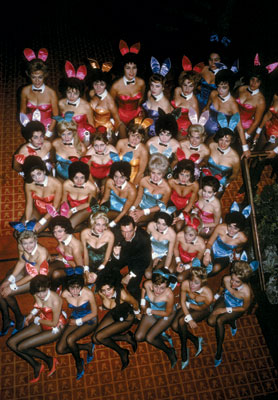

Inside, on good nights, amid the paintings of Picasso and de Kooning, amid the carved oak filigrees and the mammoth corniced pillars, jazz wailed, martinis rattled, Bunnies grooved, frugging up a storm. All such happenings took place just one flight above the indoor tropical pool, whose cave of hidden love—the Woo Grotto, it was called—was visible only to those who peeped down through a trapdoor, also hidden, in the ballroom floor. Those who swam elsewhere in the pool, meanwhile, could be viewed through a picture window in the subterranean underwater bar, most easily reached by sliding down a brass firepole. (Both

Dean Martin and Batman reportedly stole Hefner’s pole notion for their respective TV shows.) Other accoutrements abounded: girls, girls, girls, of course, plus secret passages and nooks, a game room, a bowling alley, a steam room, fourth-floor Bunny dormitories (

convenience!

), red-liveried housemen, a 24-hour kitchen, spiral stairways, an electronic entertainment room (replete with early Ampex videotape recorders in the era when your basic video recorder cost twenty grand), and a hi-fi stereo console the length of a limousine with state-of-the-art features—hissless bliss. Then, too, there was his prized gold-fauceted Roman bath, which comfortably seated eight beneath a gentle spray of drizzle mists. As such, the Master of the Mansion could do, or view, whatever he wanted whenever he wanted it.

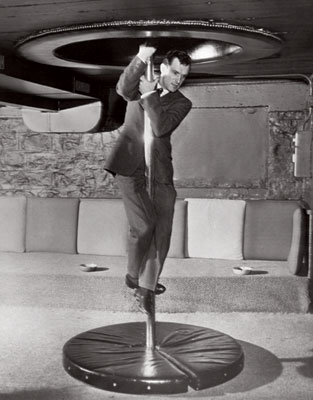

Most important, however, without question, there was the Round Rotating Bed—historic! The Bed that launched a thousand hips! The most famous bed in the annals of time!

The

Bed, period.

But we will get back to that soon enough.

Y

ou Are Where You Live

Your pad—or your crib, as it’s now called—is key. It’s an extension of who you are. And it’s the environment in which you are going to be spending some of the best times of your life. So it should be a projection of your own personality.

T

he Existential Importance of Hef’s House Explained

Playboy

cartoon, 1970: A man has clambered to a mountain peak to beg wisdom from a cross-legged guru. Guru tells man: “In a place called Chicago…there’s a man who lives in a mansion full of beautiful women and wears pajamas all the time. Sit at his feet and learn from him, for he has found the secret of true happiness.”

Pallor—however defiant, however triumphant—will wear upon a man’s soul, alas. The Great Indoors, the Pneumatic Era, the Chicago Hermitage eventually began to fatigue its chief proponent; he needed fresh air; he took flight. On the Big Bunny, his glorious jet-black DC-9, he flew west, to Los Angeles, birthplace of his formative Hollywood dreams, where show business wanted his business more than ever. He flew there and flew there until a house was found to keep him there. Paradise found: January 1971. Barbi saw it first and advised him of it; besotted by the splendor, he bought it in February. A baronial Tudor manor perched atop the greenest of slopes, set on five and a half acres of what would become his Eden—this was his Hollywood sequel: “A new Playboy Mansion for a new decade,” he would say, “interconnected to nature as the Chicago Mansion could

never be. I had found the place where I would live out my life, and do my best to create a heaven on earth.”

Playboy Mansion West would forever be the prettier sister, the sun-drenched blonde versus the dusky brunette, appropriately curvier of terrain, and what foliage! Heaven could only hope. Here, in this soft crook of Charing Cross Road—pristine epicenter of Holmby Hills—he would design his Shangri-la from scratch, take a great barren backyard (save for Southern California’s only stand of redwoods) and install an oasis, verdant and wet. Like a Midas possessed, he oversaw all minutiae:

“Where the hell are my lily pads?”

he famously inquired at one early juncture. Soon the property that had come sans pool had its own lagoon, with waterfalls spilling over a Grotto of steaming whirlpools beside koi ponds set in rolling lawns on which flamingos mingled with peacocks, cranes with ducks, a llama nibbled flowers, and—poetically—rabbits ruled. Wildlife flourished, but so too did the Wild Life, amongst and betwixt consenting adults—and this, of course, is what gave the lay of the land, if you will, its legacy.

Naturally, then, the libertine seventies found their test laboratory at Mansion West: Monkeys swung in the trees, but humans swung everywhere else. Hef had arranged the accommodations—even the Game House had mirrored love nooks. Meanwhile, his own Master Bed West, not round but extra vast, with nude nymphs carved in oak relief, with automated movable curtains and mirrors and

headboard—he would ride the box springs therein like a sultan on his magic carpet!