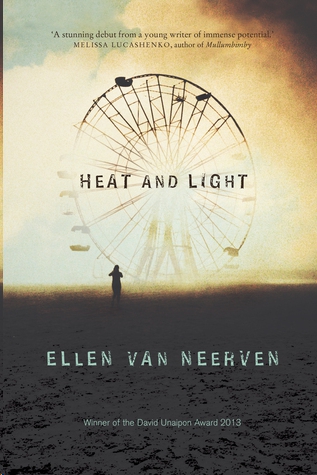

Heat and Light

Authors: Ellen van Neerven

Tags: #Science Fiction, #Historical, #Cultural Heritage, #Literary, #Short Stories (Single Author), #Australia

Ellen van Neerven (b. 1990) is a writer of Mununjali and Dutch heritage. She belongs to the Yugambeh people of the Gold Coast and Scenic Rim. She won the David Unaipon Award – Unpublished Indigenous Writer in the 2013 Queensland Literary Awards for

Heat and Light

. Ellen’s short fiction, poetry and memoir have been published in numerous publications, including

McSweeney’s

,

Voiceworks

and

Mascara Literary Review

. She lives in Brisbane.

Contents

HEAT

Pearl

It was a slight, old woman in a pie shop off the highway that told me who my grandmother was. I barely saw her over the counter but she propped herself up with one foot on the skirting board and pointed at me accusingly.

‘You’re a Kresinger,’ she spat. ‘I have something for you.’ She tried to put what looked like a wood whistle in my palm. ‘This was your grandmother’s. She worked here.’

‘No,’ I said. ‘My grandmother was Marie. Passed now, but she’s my grandmother.’

‘Sister,’ the woman behind the counter said. ‘That was your grandmother’s sister.’ She told me a story, starting with my grandmother’s real name, Pearl.

~

The first time Pearl Kresinger was taken by the wind we were both twelve. It had been raining so long the water reached the library of our school on the hill. But it was the wind, cyclonic, that kept anyone with common sense inside. Not Pearl. She went out on the beach. She was standing on the jetty star-posed and everyone saw her. She seemed to fight with the wind for a moment, her torso wrenched back and her chin to the sky, but then we saw her fall into the grey water.

Trying to save her, one man yelled out he had felt her skin. But in the next wave he was gone.

A day later she came out with her hair streaked white, and the wind had settled. She didn’t stay at school, none of them did, though I tracked her over the years.

Her skin was burnt butter, her forehead small and high, her fingers straight, her nails blue-grey from a permanent chill. She wore a red floral dress that dropped off her narrow shoulders. Her now black and white hair was waxy and feather-like, stretching down her back and creeping from behind her ears into her mouth when she turned to you. I could tell what others couldn’t, her ears weren’t really there, her eyes hissed and some of her teeth were missing. But the men followed the dance of her hair from back to mouth.

When the wind was kicking in and I’d be walking home from school near the beach through empty car parks, before the streetlights turned on, I’d see her between buildings, her hair entwined, her face in someone’s neck, a man mostly, though there were women. It seemed all were hopeless against her.

After school I moved across the border and off the coast to a stopover town and got a quiet job behind the counter serving truckies.

I heard about the freak storm in the early fifties, Pearl Kresinger cheating death for the second time. The wind ripped the Kresinger tent up, into a tree. The others ran for shelter and Pearl stood there and let it lift her, she went into the electricity wires and they curled into each other like lovers as she was jolted. Her brother moved to her lifeless body and she touched him, and he took her place.

The people of the town drove her out of there. Nobody would touch her again. She lived in the hills for a while, and then she came to my town, and into my store.

I was jealous at the sight of her. The truckies passing through the store did not know of her curse.

It wasn’t just that she was Bundjalung that made them think she was beautiful. It was the way she duck-called.

~

I tug at the traffic all the way back to the city, and quickly go into the house I grew up in. I find my father – on the back stairs, painting – who denies everything the old lady has told me. He spills paint three times on his boot, so I know I have to go back.

My thoughts are running wild as I drive to my place. If I didn’t know my grandmother, then how could I know myself? My grandmother as I had always known was Marie Kresinger, Aunty Marie to everyone. She’d spent most of her life as a domestic. She died from heart failure at the age of seventy-two. People said her heart was too big. I was eleven. My dad wanted me to sing an old-time song at the funeral but I was too shy.

She was the daughter of Zahny Zahny, otherwise known as Jack Zahn Kresinger. He was one of the men the settlers gave the title of King of his people. Zahny Zahny had three wives and ten children; Marie had many half-sisters and brothers, and maybe I had heard the name of one of her sisters, Pearl, in passing. Grandmother Marie wasn’t here to tell her own story, and my father would tell me nothing about our history, whether he knew it or not. This leaves me with the shopkeeper. It is Sunday afternoon, after closing time. I will have to go back down the freeway tomorrow, to the pit-stop just over the border.

I grip the wheel to hear my thoughts. I am Amy Kresinger, twenty-six and already war-weary with life, already feeling pushed into the ground like some sedated potplant.

The usual reason I go down the highway and to ancestral country is to go surfing, not to meet family or do any of the practices you’d expect me to do.

I thought I was going to become a nice woman one day, get married, have a cosy family, and be called Aunty, all because of my grandmother Marie. I thought I’d mellow and tame with time. Now I’m not so sure.

When I arrive back at Jimmy’s Pies the old woman is rolling up the doors, no one beside her. This old woman can spin a yarn. She puts her whole body in it.

~

There is a kind of woman that draws men like cards, that has beauty, and knowledge as well in those siren eyes. That’s Pearl Kresinger. Jimmy hired her before she even opened her mouth. She was put in the kitchen with him. He said every morning, 6 a.m. It didn’t feel kosher, at that time, in the sixties, to have a black woman working at your establishment. That’s why Jimmy put her in the kitchen, I assumed, though she wasn’t out of sight. When the pies were in the oven baking, she was out there on the tables.

I don’t know where she learnt to duck-call. Women don’t duck-call, at least not where I’m from.

There were three men who usually came in most mornings around eleven. They’d shot a few thousand roos, rabbits and camels between them, but what they all had in common was the ducks. One of the men had lost sight in one eye. They called him Bandit for his eye-patch. I’d heard he was in a highway crash when he was younger. Two roos went through the windshield.

I was behind the counter half the time and swept the floors and ran errands for Jimmy the rest. I melded in – I was invisible when they wanted me to be.

The shop was a brothel before they made the highway. Then it was a warehouse for sporting goods. Jimmy had bought the place and done it up a year before I’d started. The cars were starting to pull in, most came from trips to and from Brisbane, which was really starting to boom.

Jimmy liked that Pearl was strong – she could carry the boxes of meat from the delivery. He was getting on, his strength was starting to decline. And compared to Pearl, I was a Chihuahua.

Although Jimmy and Pearl started before me every day, they did most of their work in the afternoons. Pearl was getting good at cutting the pastry, learning the techniques. Sometimes I watched her from where I was standing and although I already felt a strong sense of responsibility and ownership of the store in what I did, I wished I was the one making the pies.

Pearl snapped the scissors when she was bored, which was often. One time we were alone and I said to her, ‘Do you remember me from school?’ She didn’t answer.

The truckies loved meat, and they loved our pies. I was sitting behind the counter when Bandit’s group came in. These three men played long games of dice as they sat there, bludging, until mid-afternoon. I listened and heard the gossip of the surrounding towns where they lived. They requested I play anything but the Bee Gees on our tiny wireless, perched on top of the glass cabinet.

The other two were opposites: Goh was a tall thin skeleton of a man, married and silent. George was fat, and the one who talked the most. Between the three of them, they mainly discussed the road, hunting and women. Jimmy would come out and talk with them. They were ex-crims, the lot of them.

The truckies were the kind of men who talk about hating native women. There was a lot around here, and Jimmy told Pearl it would be best for her not to come out while they were there.

‘Bad men,’ Jimmy said to her. ‘But they’re half my business.’

Pearl didn’t listen, of course, and one day when they were talking about wildfowl she went out and sat down at their table. They looked at Pearl as if she was possessed. They were dazzled by her stories, and of course the flash of pale on her brown body, her well-positioned cleavage.

The men didn’t look at me. I was just a short woman. Pearl and I were the same age, going on thirty, though she trumped me in conversation. No one looked at me twice, I was big-eared, pale and freckled.

Pearl bragged about catching ducks, even said we should start selling duck pies here. The men were dim, they didn’t see her for what she was.

~

I am like my grandmother Pearl. I am a strong black woman, and love comes too easy for me. There is always someone to drown. I have those Bundjalung eyes, too.

My father doesn’t know that I go to those coffee shops in the inner-west, where the older, wealthy women go, women who like women.

It is always a bit of an intellectual seduction. I offer to buy them a cuppa, ask them what they’re reading. Women like that are always reading. Searching for women like them in the texts. True they’re always keen, their hand movements on the tabletop say it.

Today I snare Shirley. I’ve been meeting her for months now, on and off. She has a long-term partner, ten years or more. Shirley is gorgeous. She is in her forties but looks thirty. Blond curls, surfer looks. A dazzling smile. Strong, masculine hands. Nails cut.

This time I meet her at the pub for lunch in the industrial section – this shows I mean business. She is sitting there when I rock up. She always wears a sports jacket even if it’s humid outside. And flash jeans that are tight at the crotch. When we finish our meal and drinks I get her to follow me along the road, under the freeway, where the milk factory is. It is 3 p.m. on a Friday and we are around the corner and out of sight of the state post office and the Murri art studio. We’re by the fence. I cup her small angled face and she grabs my collar as we kiss, our crotches already pressing together. Her jeans are easy to undo and I slip my hand in that small gap between her underwear and the hot centre of her. She groans like I knew she would and she roughly palms up my skirt, pulls my thong down to my knees. I lift up the hem of the skirt and pull her to me. We give up on kissing. A train vibrates the tracks above us, and the shudder goes to the ground.

Driving home I switch on the radio and one of those old Motown voices comes on and reaches my heart. I have a boyfriend. He’s a teacher. When I first met him I thought I could marry him. Now I say I’m too busy to meet on weekends and he should be catching up on his marking. I don’t want to be the person who captures the hearts of many.

I am often stirred by a woman walking down the street or at a bus stop. In my teens, I was one of the ones every Friday night in the last carriage on the 1 a.m. train having sex with anyone who would have me. I am cursed to be this.

I remember the next half of the story the old woman told me.

~

Pearl Kresinger had only been in town for a week or two but she was already known for her duck calls, people in town had seen her by the waterways. She always wore her call around her neck, between her breasts, so the men couldn’t help but notice it.

Goh, Bandit and George were obsessed with wildfowl hunting, a distraction from their meandering lives. Individually they were hopeless, but as a group they got some luck, they weren’t too bad. They talked of the Pacific blacks and the hardheads.

‘What do you go after?’ Bandit asked Pearl.

‘The mallards,’ she said, surprising them.

‘How many?’ Goh asked.

‘Fifteen, once. Or more.’

There was a silence. Standing there, behind the counter, I knew they’d never shot that many in their life. Bandit seemed to make a decision. He pointed to the wood whistle around her neck. ‘Show us.’

She tugged at the string and brought it to her lips. It was a noise that sounded nothing like her voice – an immersive murmur that carried across the shop and lasted a total of four seconds. I was holding my breath and I didn’t know why. Her body, her thick brown arms seemed to shine into a bronze and the men couldn’t keep their eyes off her.

I wished I had an excuse to go outside and not watch them inflate with her. I could go to the car park and stand looking at the cars and maybe have one of Jimmy’s cigarettes, even though I hadn’t smoked in years.

In their thick silence, the men were in agreeance that they couldn’t replicate such a natural vocalisation.

‘You should come out with us sometime,’ Bandit said.

‘You’d be our little luck charm,’ George said, wiggling his fingers.

Pearl played with her lips, ‘But I got no gun.’

‘We do.’

She twirled her hair, and I saw the different bits of colour, the streaks of deep white, the etch of electricity.

‘Show us again,’ Bandit said firmly.

They made her draw the call until her eyes teared up.

Bandit said, ‘You reckon fifteen. You’re going to have to prove it.’

~

I carried a special sort of shame from not singing at my grandmother’s funeral. Everyone said Aunty Marie was a classy sort of woman; in photos, she was always looking flash in opals and her hair all up and everything. I know I come from a different era, but dressing up for me is leaving the thongs at home and collapsing my ponytail.

I initially rejected the thought of Pearl being my grandmother. What the woman at the pie shop had said about her made her sound like a succubus, cursed, a monster. I wanted eventually to be the baking biscuits type, like Aunty Marie; I honestly believed I would get there one day. I told my father and the other mob at the youth centre I outgrew singing, like it was a pair of shoes. But I do sing to myself sometimes, when I can’t go to sleep.

Marie Kresinger had two children older than my father, a boy and a girl. She was raising them out at Hune Hill, on the family’s property, when Pearl must have come to see her with news of her pregnancy. Their father had recently passed and Marie, her husband and the kids had moved back into the house at Hune Hill after living in Brisbane. Marie had been living in Brisbane ever since she’d married at the age of eighteen.