Hawkwood and the Kings: The Collected Monarchies of God (Volume One) (22 page)

Read Hawkwood and the Kings: The Collected Monarchies of God (Volume One) Online

Authors: Paul Kearney

Tags: #Fantasy

"It is there in the sheets I copied for you," Murad said sharply. His scar rippled on his face like a pale leech.

"You may not know what should be copied and what should not. You may not have given me everything I need to navigate this enterprise with any safety."

"Then you will have to come back to me, Captain. There will be no more discussion of the matter."

Hawkwood was about to retort when he heard a cry beyond the cabin.

"

Osprey

ahoy! Ahoy the carrack there! We've a passenger for you. You left him behind, it seems."

Hawkwood glanced at Murad, but the nobleman seemed as puzzled as himself. They rose as one and left the cabin, stepping along the passage to the waist of the ship. Billerand and a crowd of others were leaning over the side.

"What is it? Who is this?" Murad demanded, but Billerand ignored him.

"Seems we left someone behind, Captain. They've an extra passenger for us, brought out in the harbour scow."

Hawkwood looked down the sloping ship's side. The scow crew had hooked on to the carrack's main chains and a figure was clambering up the side of the ship, his robe billowing in the sea breeze. He laboured over the ship's rail and stood on deck, his tonsured head shining with effort.

"The peace of God on this ship and all in her," he said, panting.

He was an Inceptine cleric.

"What foolishness is this?" Murad shouted. "By whose orders are you come aboard? You there, in the boat - take this man off again!" But the scow had already unhooked and her crew were pulling away from the carrack, one waving as they went.

"Damnation! Who are you, sir? On whose authority do you take ship with this company?" Murad was livid, furious, but the Inceptine was calm and collected. He was an oldish man, white-haired, but ruddy and spare of feature. His shoulders were rounded under the habit and he had the stocky build of a longshoreman. The Saint symbol glinted at his breast.

"Please, my son, no blasphemy on the eve of so great an undertaking as this."

For a moment Hawkwood thought that Murad was going to draw his sword and run the priest through. Then he spun on his heel and left the deck, disappearing down the companionway.

"Are you the master of this vessel?" the Inceptine asked Hawkwood.

"I am Richard Hawkwood, yes."

"Ah, the Gabrian. Then, sir, might I ask you to find me some quarters? I have little in the way of belongings with me. All I need is a space to lay my head."

Men were gathering in the waist, soldiers and sailors both. The sailors looked uneasy, even hostile, but the soldiers seemed pleased.

"Give us a blessing, Father!" one of them cried. "Call God and the Saints to watch over us!"

His cry was taken up by a score of his comrades. The Inceptine beamed and held up an open hand. "Very well, my sons. Kneel and receive the blessing of the Holy Church upon your enterprise."

There was a mass movement as the soldiers knelt on the deck. A pause, and then most of the sailors joined them. The ship creaked and rolled on the swell, and there was almost a silence. The Inceptine opened his mouth to speak.

In the quiet came the four, distinct, lovely notes of the ship's bell marking the end of the second dog-watch, and the turn of the tide.

"All hands!" Hawkwood roared instantly. "All hands to weigh anchor!"

The sailors leapt up, and the waist became a massive confusion of figures. Billerand began shouting; some of the kneeling soldiers were knocked sprawling.

A series of orders were bandied back and forth as the seamen hurried to their duties. There were casks, crates, boxes and chests everywhere on the deck and they, along with the bewildered soldiers, impeded the working of the ship, but there was no help for it; the hold was filled to capacity already. Hawkwood and Billerand shouted and shoved the crew to their well-known stations, whilst the cleric was left with his hand hanging impotently in the air, his face filling with blood.

In a twinkling, the crew were in position. Some were standing by at the windlass and the hawse-holes ready to begin winding in the thick cables that connected the ship to the anchors. More were busy on the yards, preparing to flash out the courses and topsails as soon as the anchor was weighed. The sailmaker and his mates were bringing up sail bonnets from belowdecks so they would be handy when the time came for lashing them to the courses for a greater area of sail.

"Brace them round!" Hawkwood shouted. "Brace them right round, lads. We've a beam wind to work with. I don't want to spill any of it!"

He felt the ship tilt under his feet, like a horse gathering its legs under it for a spring. The ebb was flowing out of the bay.

"Weigh anchor! Start her there, at the windlass. Stand by at the tiller!"

The anchor ropes began to come aboard, mud-slimed and foul-smelling. They were like thick-bodied serpents that slithered down the hatches to be coiled in the top tiers by men below.

"Up and down!" a sweating master's mate cried.

"Tie her off," Hawkwood told him. "On the yards there - courses and topsails. Bonnet on the main course!"

The crackling and booming expanses of creamy canvas were let loose, billowing and filling against the blue sky. The carrack staggered as the breeze hit her. Hawkwood ran up to the quarterdeck. The ship had canted to larboard as the sails took the wind.

"Brace her, brace her there, damn you!"

The men hauled on the braces - ropes which angled the yards at the best attitude to the wind. The carrack began to move. Her bow dipped and cut through the rising swell, coming up again with the grace of a swan. Spray flew round her bows, and Hawkwood could feel the tremor of her keel as it gathered way. He looked across at the

Grace

and saw that she was pulling ahead, her great lateen sails like the wings of some monstrous, beautiful bird. Haukal was on her quarterdeck, waving and grinning through his beard like a maniac. Hawkwood waved back.

"Let loose the pennants!"

Men on the topmasts shimmied up the shrouds and pulled loose the long, tapering flags so that they sprang free at the mastheads, snapping and writhing in the wind. They were of shimmering Nalbeni silk, the dark blue device of the Hawkwoods at the main and the scarlet of Hebrion on the mizzen.

"Light along the log to the forechains there! Let's see what she's doing."

Men ran along the decks with the log and rope that would let them know the speed of the carrack once she had fully taken the wind. Hawkwood bent down to the tiller hatch.

"Helm there, west-south-west by north."

"Aye, sir. West-south-west by north it is."

The larboard heel of the carrack became more pronounced. Hawkwood hooked an arm about the mizzen backstay as the ship rose and dipped, cleaving the waves like a spearhead, her timbers groaning and the rigging creaking as the strain rose on it. She would make a deal of water until the timber of her upper hull became wet and swollen again, but she was moving more easily than he had dared hope, even with the heavy load. It must be the ebb tide, pushing her out to sea along with the blessed wind.

The soldiers had mostly been cleared from the decks, and the Inceptine had vanished below, his blessing unsaid. Some of the passengers were in sight, though, being shunted about by sailors intent on their work. Hawkwood saw Murad's cabin servant, the girl Griella. She was on the forecastle, her hair flying and the spray exploding about her. She looked beautiful and happy and alive, her eyes alight. He was glad for her.

He stared back over the taffrail. Hebrion and Abrusio were sliding swiftly astern. He guessed they must be doing six knots. He wondered if Jemilla were on her balcony, watching the carrack and the caravel grow smaller and smaller as they forged further out to sea.

The

Osprey

rose and fell, rose and fell, breasting the waves with an easy rhythm. The sails were drum-taut; Hawkwood could feel the strain on the mast through the twanging-tight backstay. If he looked up all he could see were towering expanses of canvas criss-crossed with the running rigging, and beyond the hard unclouded blue of heaven. He grinned fiercely as the ship came to life under his feet. He knew her as well as he knew the curves of his wife's body; he knew how the masts were creaking and the timbers stretching as his ship answered his demands, like a willing horse catching fire from his own spirit. No landsman could ever feel this, and those who spent their time politicking on land would never know the exhilaration, the freedom of a fine ship answering the wind.

This

, he thought,

is life; this is living. Maybe it is even prayer.

The two ships sailed steadily on as the afternoon waned, leaving the land in their wake until Abrusio hill was a mere dark smudge on the rim of the world behind them. They crested the rising swell of the coastal sea and touched upon the darker, purer colour of the open ocean. They left the fishing boats and the screaming gulls behind, carving their own solitary course to the horizon and setting their bows toward a gathering wrack and fire of cloud in the west, a flame-tinted arch which housed the gleam of the sinking sun.

Part Two

In

D

EFENCE

of the

W

EST

Twelve

T

HEY HAD BEEN

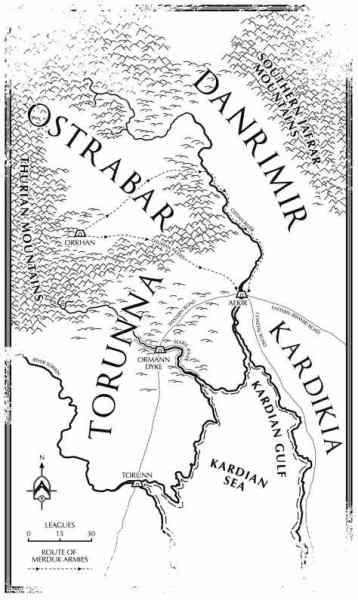

three weeks on the road, this giant convoy, this rolling city. They had fought against slime and snow and marauding wolves to force the waggons over the narrow passes of the Thurian Mountains before beginning the long, downward haul to the green plains of Ostrabar beyond.

The Sultanate of Ostrabar, now first in the ranks of the Seven Sultanates, its head, Aurungzeb the Golden, one of the richest men in the world - or he would be when this caravan reached him.

This had been a Ramusian country once, a settled land of tilled fields and coppiced woods with a church in every village and a castle on every hill. Ostiber had been its name, and its king had been one of the Seven Monarchs of Normannia.

That had changed with the advent of the Merduks sixty years ago. They had poured over the inadequately defended passes of the terrible Jafrar Mountains to the east, crossed the headwaters of the Ostian river and had overrun Ostiber in less than a year, exposing the city of Aekir's northern flank and coming to a halt only when faced with the defended heights of the Thurians manned by grim Torunnans who included in their ranks a youthful John Mogen. Ostiber had become Ostrabar, and the wild steppe chieftain who had conquered this country took that as his family name. The captain of his guard had been Shahr Baraz, who would in time rise to command all his armies. And his sons, when they had finished poisoning one another, became sultan after him. Thus was the Kingdom of Ostiber lost to the west, its Royal line extinguished, its people enslaved, tortured, ravished and pillaged and, worst of all, forced to change their faith so their eternal souls were lost to the Company of the Saints for ever.

Thus were the children of the Western Kingdoms taught. To them the Merduk were a teeming tribe of savages, held at bay only by the valour of the Ramusian armies and the swift terror of horse and sword and arquebus.

For the folk living in Ostrabar now it was different. True, they must needs pray to Ahrimuz every day in one of the domed temples that had been erected throughout the land, and they yielded yearly tribute to the Sirdars and Beys who now inhabited the hilltop castles; but there had always been nobles in the castles exacting tribute, and they had always prayed. The terror of the first invasion was long past, and many descendants of those who had fought in Ramusian armies six decades before wielded tulwar and scimitar in the ranks of Aurungzeb's regiments.