Hawk Moon (5 page)

"By the way, you know Clarence at the radio up front?" she asked me.

"Uh-huh."

"He's the Chief's nephew."

"Oh."

"But it's not what you think. The Chief is pretty nice to Indians. He was raised here and he went to 'Nam with two of my uncles and they got along fine. In fact, the whole generational thing is pretty weird."

"The whole generational thing?"

"Yeah, it's like bigotry skipped a generation or something. The hippie generation got along fine with each other – the whites and the reservation Indians, I mean. But then my generation came along and we don't get along so well. Now it's like it used to be – the way Clarence is, I mean." She grinned her charming grin. "You want the tour?"

"I'd love the tour."

"Well, that's a wall and that's a light socket and—"

I laughed.

She went over and opened up the window.

The night came rushing in, a tide of fading heat and starlight and fireflies and the faint laughter of children and the booming radios of teenagers as they drove up and down the main street.

Her office contained a small wooden desk atop of which sat a sassy new computer. There was a chair that matched the desk and a chair that didn't match the desk. That was the one I sat down in. I faced two battered filing cabinets.

She came over and sat down and turned on her computer. "Have you figured out why I wanted you to come over here tonight?" she asked.

"I've got a pretty good guess."

"Sandra Moore."

"The one who was killed and had her nose mutilated?" I said.

"Right. I want to find out who killed her."

"I guess that's your job," I said quietly.

"I don't mean just because I'm a cop."

"Oh?"

"No. A lot of people in this town think my husband did it."

And for the first time I made the connection I should have made much earlier. A small town; Native Americans. How many people named Rhodes could there be? The bruiser had called the Indian he'd been whumping on "Rhodes".

And the fetching woman sitting across from me was named Rhodes. So that meant—

Never let it be said that the obvious ever slips past me. "Does your husband deal blackjack in the casino?"

"Yes. Why?"

"He had some trouble tonight."

"What kind of trouble?"

I saw the quick panic in her eyes and was sorry I'd said anything. "He's all right now," I reassured her. "A couple of unfriendly guys from Cedar Rapids worked him over some."

"Do you know why?"

"No. They said he was ‘nosing around in their business.’ I'm not sure what they were talking about. I wanted to speak to your husband but he went right back to work."

She sighed, stared out the window for half a minute or so. "I guess I shouldn't call him my husband." She turned back to me. All the luster was gone from her eyes. "We haven't lived together for three or four years. Ever since my second miscarriage." She glanced down at her small brown hands. "That was the funny thing. Women are the ones who are supposed to take miscarriages so hard. And I did. I even ended up seeing a shrink over in Iowa City. But David . . . he really took it hard. That's when he started drinking and running around—" She stopped. And suddenly the grin was back and so was at least some of the luster in her eyes. "But now I'm using you as a shrink, aren't I?"

"I don't mind."

"I'll bet you don't. You seem like a very decent guy, you know that?" She assessed me again the way she had earlier, except this time she seemed more interested in my soul than my body. "But you seem sort of sad, too, you know?"

"My wife died."

"Oh, God. I'm sorry. When?"

"Couple of years ago."

"Cancer?"

"Brain aneurism. We were standing in the kitchen just talking and—"

"I really am sorry."

I smiled. "Now I'm using you as a shrink."

"Well, I'll say what you said to me — I don't mind."

We looked at each other a long moment and then she said, "I guess we probably should talk about the murder, huh?"

"Probably be a good idea."

"Where should we start?"

"Why don't we start by you telling me why some people think your husband killed that woman?"

"Yeah, I guess that would make sense, wouldn't it?"

Only the black male was held in lower regard than the Indian man. Invariably, when a local white was murdered, and there were no handy suspects, Indian males were questioned by police.

Professor David Cromwell's Indian Journal

May 12, 1903

Chief Ryan didn't want to create a scene — it was just after suppertime and the potential for a crowd of onlookers was great — so he went over to the livery stable alone. He wore street clothes, his five-pointed badge on the breast pocket of his Edwardian-cut jacket, and he carried his old Remington .36, which he'd had altered so it could use metal cartridges instead of the original paper ones.

The way he figured things, there wouldn't be much trouble.

The young Indian man he suspected of killing the Indian girl the other night had a room above the livery and was said to be there right after suppertime most nights. He was also said to have argued violently and publicly with the girl on the afternoon of her death. And he had an extremely bad drinking problem. Ryan felt sure he had his man. Now it was simply a matter of arresting him, hopefully without incident.

A

fter supper, Anna Tolan went back to the crime scene. She wanted to comb a particular area of grass once more before the rain came and washed all the evidence away.

She spent half an hour at the scene and then walked back toward town.

As a farm girl, she was always properly thrilled by Cedar

Rapids. Nearly 30,000 population now, electric lights, more than 2,000 telephones, electric trolleys and theaters that saw some of the world's biggest acts play here. She loved window-shopping, too, especially since the large floral hats were in for spring. She was saving her money up to buy one.

Even from the back, she recognized him. Chief Ryan. Walking fast. Alone.

She caught up with him. "Good evening, Chief."

"Hi, Anna." But he didn't sound as hearty as usual. In fact, he didn't sound all that happy to see her.

She walked along with him. In silence. "Everything all right, Chief?"

"There could be a little trouble, Anna."

"Oh?"

"The Indian girl."

"Uh-huh?"

"I think we've got our man: I'm just going to arrest him now. I don't think it's any place for you, Anna, and please don't take that the wrong way."

"I have my own gun."

"I know you do."

"And I'm a good shot."

"I know you are."

"So I'm perfectly capable of taking care of myself." Mrs. Goldman, who was educated, always said things like "perfectly capable", and Anna loved the sound of such words in her ear and the feel of them on her very own tongue.

The Chief sighed. "So in other words, you want to go along."

Anna nodded. "Yes, I do. But I should tell you one thing."

"Oh?"

"I don't think he did it."

"You don't, eh? Is this more of your "scientific detection?"

"Uh-huh."

"Well, now's not the time for it, Anna. We've got our man and we've got him good so if you want to go along with me to arrest him, can you please just be quiet about your scientific detection for once?"

Anna said, "I'm perfectly capable of being quiet when I need to be, Chief."

5

I'

ll tell you a secret about sexual homicides: the stranger the better where the FBI's psychological-profile group in Quantico, Virginia is concerned.

There's a good reason for this. Find a man in an alleyway who has been murdered by a blow with a beer bottle, and your lists of suspect types will be virtually endless. Many different kinds of people are capable of committing a homicide such as this one. The death might even have been justifiable homicide — maybe the killer was a woman fending off a rape.

The case that the Bureau often points to as a seminal one took place in October, 1979. The victim was a white twenty-six-year-old teacher who had been found on the roof of an apartment building. The killer had sliced off her nipples and written

Fuck you. You can't stop me

in ink on the inside of her left thigh.

The nature of the crime narrowed the scope of the investigation immediately and significantly. After studying the crime scene and the Coroner's reports, the three agents working on the case began listing some assumptions about the killer. He would be:

White

25-35 years old

a high-school drop-out

living by himself (or with a parent)

intensely interested in pornography

New York homicide detectives took this and all the other data in the profile and began checking the immediate neighborhood where the woman had been murdered.

Three days later, they started interviewing a man who was:

white

30 years old

lived with his father

had a large collection of pornographic magazines

lived in the same building as the victim

That's what I mean by the stranger the better where sexual homicides are concerned. The very nature of the atrocity helped focus the investigation. As far back as 1955, the Bureau started keeping extensive records of bizarre murders. By now, they have thousands of detailed profiles of sexual sociopaths. This is coupled with a lot of other information weather conditions at the time of a murder, the political and social environment, domestic setting, employment, reputation, habits, fears, physical condition, criminal history (if any), family relationships, hobbies, social conduct — and then the autopsy report with toxicology/serology results, autopsy photographs, and photographs of the cleansed wounds. And that's just the opening phase of the investigation.

"I

tried to get things ready for you," Cindy said. "I hope I used the right forms and everything."

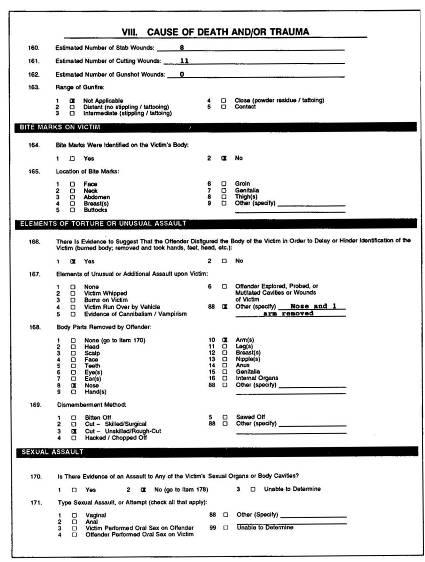

She handed me a formidable stack of papers from her desk. The top page bore the familiar logo of VICAP (The Violent Criminal Apprehension Program), the standard report used by both the Bureau and an increasing number of law-enforcement departments throughout the country. "Take a look at Form 8, will you? I'm not sure I filled that out right."

I looked at Form 8 of the report.

"It looks fine," I said. "But why don't you just tell me a little more about it first."

She glanced away out the window again. The temperature had dropped five degrees during the twenty minutes I'd been in here. You could smell rain. There was a hazy glow around the silver quarter-moon.