Hatchepsut: The Female Pharaoh (5 page)

Read Hatchepsut: The Female Pharaoh Online

Authors: Joyce Tyldesley

Tags: #History, #Africa, #General, #World, #Ancient

Sobeknofru was succeeded by an unrelated king, and the 13th Dynasty started to follow very much in the tradition of the 12th. However, no strong royal family was established and there was little apparent continuity between the monarchs traditionally assigned to this period. Instead, a succession of short-lived kings and their increasingly powerful viziers reigned over a slowly fragmenting Egypt, and the country gradually disintegrated into a loose association of semi-independent city states. A series of freak Nile floods at this time, and the resulting strain on the Egyptian economy, must have seemed a very bad omen; the regular rise and fall of the Nile was taken as a general sign that all was well within Egypt and the 13th Dynasty rulers must have been unpleasantly reminded of the very low floods which had heralded the collapse of the Old Kingdom. They would have done well to heed the omen. The end of the 13th Dynasty saw the ‘official’ end of the Middle Kingdom and the beginning of the Second Intermediate Period (Dynasties 14 to 17), a badly recorded phase of national disunity and foreign rule sandwiched between the well-documented stability of the Middle and New Kingdoms.

Tutimaios. In his reign, for what cause I know not, a blast of god smote us; and unexpectedly from the regions of the east invaders of obscure race marched in confidence of victory against our land… Their race as a whole was called Hyksos, that is ‘king-shepherds’, for

Hyk

in the sacred language means ‘king’ and

sos

in common speech is ‘shepherd’.

4

Throughout the Middle Kingdom there had been a persistent influx of ‘Asiatic’ migrants from the east, Semitic peoples who were attracted by Egypt's growing prosperity and who were themselves being pressured westwards by immigrants from further east; this was a time of population shifts throughout the entire Eastern Mediterranean region. The new arrivals were accepted by the locals and merged peacefully into the existing towns and villages of northern Egypt.

5

During the 13th Dynasty, however, these groups started to form significant and partially independent communities in the Nile Delta. At the same time the previously emasculated local rulers were gradually gaining in power as national unity began to crumble. Slowly the country resolved itself into three mutually distrustful regions, each ruled concurrently by different dynasties. The Nubian kingdom of Kerma developed in the extreme south, a small group of independent Egyptians controlled southern Egypt from Thebes (17th Dynasty), and the north was ruled by a group of Palestinian invaders known as the Hyksos (15th Dynasty) and their Palestinian vassals (16th Dynasty).

6

It was the Hyksos invaders who made the deepest impression on the historical record, ruling over northern Egypt for over a hundred years and taking the eastern Delta town of Avaris (a corruption of the Egyptian name

Hwt W'rt,

literally ‘The Great Mansion’ or ‘Mansion of the Administration’, modern Tell ed-Daba) as their capital. To the south the native-born Theban rulers remained independent and relationships between north and south were initially peaceful, if distrustful; the southern kings were able to lease grazing land from their Hyksos neighbours and there is even some evidence to suggest that Herit, a daughter of the final Hyksos king, Apophis, may have married into the Theban royal family. The Hyksos were certainly on good terms with the Nubian rulers of Kerma, to the extent that the same Apophis, towards the end of his 33-year reign and no longer on such friendly terms with his immediate neighbours, felt free to urge the Nubians to invade the Theban kingdom in order to distract the Theban army and so protect

his own position in the north. A letter written by Apophis to the King of Kush and fortuitously intercepted by troops loyal to the Theban King Kamose, details his plotting:

… Have you [not] beheld what Egypt has done against me… He [Kamose] choosing the two lands to devastate them, my land and yours, and he has destroyed them. Come, fare north at once, do not be timid. See, he is here with me… I will not let him go until you have arrived.

7

Egyptian legend as typified by Manetho regards the Hyksos as an uncivilized, brutal band of invaders and their reign as a dark, never-to-be-repeated period of chaos and mayhem:

… By main force they [the Hyksos] easily seized [Egypt] without striking a blow, and having overpowered the rulers of the land, they then burned our cities ruthlessly, razed to the ground the temples of the gods, and treated all the natives with a cruel hostility, massacring some and leading into slavery the wives and children of others…

8

This lament is, to a large extent, merely the conventional expression of horror at the realization that despised and culturally inferior foreigners could actually conquer the mighty Egypt. Exaggeration was an accepted and even expected component of historical narrative and the Egyptians saw no harm in re-interpreting their own past as and when necessary. The deeply held belief that their land could only flourish under a divinely appointed Egyptian pharaoh was certainly strong enough to distort the historical record in this instance. Archaeological evidence, less obviously biased, makes it clear that the hated Hyksos, far from inflicting barbaric foreign practices on their new subjects, made a determined effort to adapt themselves to the customs of their adopted country. The new rulers retained a few of their own traditions: architectural styles and pottery forms now show a distinct Near Eastern influence, the war goddess Anath or Astarte was quickly absorbed into the Egyptian pantheon as ‘Lady of Heaven’ and her consort, the Egyptian god Seth, became the chief deity. However, in most other respects the Hyksos surrendered their own identity as, with the zeal of new converts, they immersed themselves in Egyptian culture, adopting hieroglyphic writing, embellishing local temples, copying Middle Kingdom

art-forms, manufacturing scarabs and even transforming themselves into Egyptian-style pharaohs by taking names compounded with ‘Re’, the name of the Egyptian sun god. Far from bringing economic disaster to Egypt, their lands were governed efficiently, making good use of the Middle Kingdom administrative framework which was already in place, and native-born Egyptian bureaucrats worked willingly alongside their new masters to ensure that the Delta region prospered under their rule. The long-term material advantages of the brief interlude of foreign rule now seem very obvious. Under Hyksos rule, Egypt rapidly lost much of her traditional isolation as trading and diplomatic links were established with a wide range of Near Eastern kingdoms, and the resulting flood of exotic and practical imports both stimulated the economy and inspired the Egyptian artists and artisans. Egypt benefited from the introduction of new bronze working and pottery and weaving techniques; there were exciting new food crops to be tested, and even a previously unknown breed of humped-back cattle. Most important of all was the Hyksos contribution to Egypt's traditional military equipment; it was their improvements, combined with the early 18th Dynasty reorganization of the army structure, which led directly to the evolution of the efficient and almost invincible fighting troops of the 18th and 19th Dynasty Empire. The Hyksos introduced new forms of defensive forts, new weapon-types (more efficient dagger and sword forms and the strong compound bow which had a far greater range than the old-fashioned simple bow) and the concept of body armour to protect the troops. The soldiers – who during the Old and Middle Kingdoms had marched into battle dressed only in the briefest of kilts or loincloths and protected by a long and cumbersome cow-hide shield – were now issued with protective jackets and a lighter, easier-to-handle tapered shield. Their most important introduction was, however, the harnessed horse and the two-wheeled horse-drawn chariot, a light and highly mobile vehicle which, manned by a driver and a soldier equipped with spear, shield and bow, quickly became one of the most valuable assets of the Egyptian army.

In the south the Theban 17th Dynasty ruled over Egypt from Elephantine to Cusae (el-Qusiya, Middle Egypt), successfully continuing many of the Middle Kingdom royal traditions but on a reduced scale and adapted to fit local conditions; the 17th Dynasty royal pyramids were

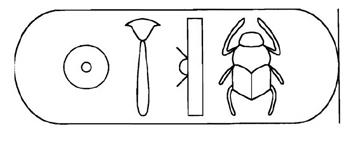

Fig. 1.1 The cartouche of King Sekenenre Tao II

relatively tiny mud-brick structures perched on top of rock-cut tombs. As the southern dynasty slowly established itself relationships between south and north gradually deteriorated, and open warfare erupted when King Sekenenre Tao II, ‘The Brave’, came to the Theban throne. A fantastic New Kingdom story which purports to explain the outbreak of hostilities starts by setting the scene:

It once happened that the land of Egypt was in misery, for there was no lord as [sole] king. A day came to pass when King Sekenenre was [still only] ruler of the Southern City. Misery was in the town of the Asiatics, for Prince Apophis was in Avaris, and the entire land paid tribute to him, delivering their taxes [and] even the north bringing every [sort of] good produce of the Delta.

9

We are told how the Hyksos King Apophis, now a fervent worshipper of the peculiar and so far unidentified animal-headed god Seth, decides to provoke a quarrel by making an intentionally ridiculous demand. A messenger is sent southwards, and he delivers the complaint to the bemused Sekenenre Tao:

Let there be a withdrawal from the canal of hippopotami which lie at the east of the City, because they don't let sleep come to me either in the daytime or at night.

Sekenenre is understandably rendered speechless by this unreasonable request: it is inconceivable that the Theban hippopotami could have been making so much noise that they were preventing Apophis from sleeping in Avaris, some 500 miles downstream. Unfortunately, the end of the story is lost, and we do not know how the king eventually replied, or indeed whether Apophis went on to make even more outrageous demands.

The more down-to-earth archaeological evidence confirms that Sekenenre Tao II fought against the Hyksos in Middle Egypt before dying of wounds sustained in battle: his mummified body was unwrapped by the French egyptologist Gaston Maspero in 1886, and examined by the distinguished anatomist G. Elliot Smith in 1906. The mummy was clearly a disturbing sight, with horrific head and neck injuries caused by repeated blows from a bronze Hyksos battle-axe:

All that now remains of Saqnounri Tiouaqen [Sekenenre Tao II] is a badly damaged, disarticulated skeleton enclosed in an imperfect sheet of soft, moist, flexible dark brown skin, which has a strongly aromatic, spicy odour… No attempt was made to put the body into the customary mummy-position; the head had not been straightened on the trunk, the legs were not fully extended, and the arms and hands were left in the agonized attitude into which they had been thrown in the death spasms following the murderous attack, the evidence of which is so clearly impressed on the battered face and skull.

10

The badly preserved body suggests that the king had been hastily mummified, not necessarily by the official royal undertakers. Sekenenre Tao II was succeeded by his son, Kamose, who ruled for little more than three years yet managed to strengthen the Theban hold on Middle Egypt. After brooding aloud on the unfortunate situation which had divided his land – ‘I should like to know what serves this strength of mine when a chieftain is in Avaris and another in Kush, and I sit united with an Asiatic and a Nubian’

11

– Kamose took decisive action. He advanced northwards towards Avaris and southwards as far as Buhen, obtaining control of the vital river trade routes and exacting vengeance on those believed to have collaborated with the enemy, before returning to Thebes where he recorded his daring deeds on a limestone stela at the Karnak temple: